China's Q1 GDP numbers

More importantly, how they fit in the context of key macroeconomic themes

China’s Q1 GDP figures were released yesterday by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), featuring headline year-over-year growth of 5.3% which came in ahead of “consensus” figures from outside analysts and observers.

In the grand scheme of things, this is only a quarter’s worth of numbers and as such there is a limit to how meaningful they are. I tend to focus on the longer-term and am using the release more as a framework to synthesize some of the higher-level macroeconomic trends that I have been discussing — mainly on Twitter/X — over the past year:

Transition from property to advanced manufacturing

China’s trading relationship with the world

Labor dynamics and structural change driven by demographics

In this essay, I will tackle #1: the ongoing transition of China’s economy from property to advanced manufacturing. My views are different from mainstream views that GDP growth and productivity are in permanent, secular decline — instead, that the Chinese economy is transitioning to a new era in which GDP growth gets a healthy boost from the structural shift into advanced manufacturing that more than offsets demographic decline in its working-age population. This goes back to the age-old question of “Will China become old before it becomes rich?”.

To understand my rationale requires stepping out very far beyond the Q1 numbers, putting them into the context of (i) three decades of growth and multiple structural economic shifts, (ii) the GDP arithmetic and mechanics of different categories of investment, and (iii) the experiences of comparable economies (during rapid urbanization) like South Korea and Taiwan. Hopefully with this context, we can better understand how the Q1 numbers fit in but even more importantly, what future GDP and other economic releases may tell us about the long-term direction of the Chinese economy.

Before getting into it, I first want to briefly comment on the value of examining primary vs. secondary sources which is relevant here as well.

Primary vs. secondary sources

I have seen a spate of commentary about the Q1 data on Twitter/X that usually links to news articles from third-party news sites instead of the original press release. As a general rule, I prefer to go to directly to the primary source, which in this case is the original NBS press release.

Every article you read about Q1 GDP that is not this NBS press release is ultimately based on the data contained in this press release. Newsrooms and media outlets will naturally take this primary source data and modify it in some way — otherwise what is their raison d’être? Even news-centric media that pride themselves on journalistic impartiality need to “add value” and this will naturally modifies the primary source data even if truly impartial. Of course there are media outlets with stated or clear goals to align certain narratives. Choosing as a starting point to re-post skewed takes is typically an endorsement of that take.

Of course, my raison d’être here is to offer my own commentary and takes and I will certainly selectively focus on certain sections of the report1 but I try my best to start with primary sources. In this case, it is relatively easy because NBS offers an English-language version of the release. What sometimes makes Chinese economic analysis more challenging is that many primary sources may not be offered in English, requiring one to review primary sources in Chinese.

I also understand why people seem to avoid posting the NBS link. First, Chinese government website design is stuck in early Web 1.0 Internet era. Typically when you try to link to these government websites on Twitter/X, it does not offer up a nice “social preview” image that you will get from bleeding-edge-in-comparison websites like Reuters. It just shows up as a partial link — often with random letters that look like spam that nobody will engage with:

Second, and more significantly, there is a tendency (somewhat understandably) for many people outside China to simply not trust anything coming from China. Linking to a Chinese government website could be seen as endorsing the article or the views contained in that article. And of course the bean counters at NBS in charge of putting together this primary source will offer their own spin and take, just like newsrooms and media outlets around the world. Indeed, just look at the title and preamble of the Q1 report:

Clearly, the bean counters want you to know that the national economy “made a good start” to the year. In my head, I imagine them as expectant puppies asking for a nice pat on the back for their efforts. And I am always amused by these long-winded preambles that seem to be a prerequisite of every government release extolling the virtues of the Communist Party of China, the Central Committee and Comrade Xi Jinping. While entertaining (at least to me), one can and should ignore the ornate writing style and focus instead on the real substance: the data.

Stripping away the noise, these press releases contain much useful data. These press releases also tend to follow the same format from release to release which allows one to look at the same trends over time. In this way, these press releases remind me of public companies and their earnings announcements. There is a lot of ritualistic fluff that you can ignore — real analysts will know where to look having seen multiple versions of the press release over the years.

There are of course some who do not even think the data itself is reliable (except it seems, when it suits a particular narrative). In this case, whether you rely on secondary sources or primary sources does not make a difference. The secondary sources are still based on the same data that is viewed as unreliable. While we always must be open to the idea that the data is manipulated, if we assume it is all wrong then there is no reason to do any analysis at all.

The point here is that analysts should always rely or at least consult primary sources. This is true whether it is Chinese data or any other data.

(1) Transition from property to advanced manufacturing

Both industrial production and fixed asset investment (FAI)2 data in Q1 confirmed the broad trend that we have been witnessing for some time now in the economy’s transition from property as a key growth driver to advanced or (as it is referred to in the press release) “high-tech” manufacturing.

This is one of the major Chinese macro themes that I have been discussing at length over the past year. One of the elements of the popular and seemingly mainstream “overinvestment” narrative is that Chinese policymakers are merely shifting investment from one flavor (property) to another (manufacturing). For advocates of this narrative, there is no meaningful difference between the two — it still represents an “imbalance” that needs fixing.

I strongly disagree with this narrative. There are fundamental differences in the nature of the underlying assets being formed and the level of maturity within the asset class’ “Pareto cycle” that warrant a deeper level of analysis to really understand impacts to aggregate GDP.

Using the “Pareto efficiency” framework to analyze economic transitions

Investing in housing and “old” infrastructure at the tail end of their pareto-optimal stages is fundamentally different from investing in advanced manufacturing at the front end of their pareto-improvement stages.

Industrial production is typically oriented towards consumption GDP while FAI represents investment GDP. At a high-level, industrial production can be viewed as the “R” and FAI as the “I” in the Return on Investment (RoI) calculation. From an “R” and “I” perspective, property and infrastructure assets behave very differently from industrial assets.

I will warn in advance that there is arithmetic and some modeling involved. But I think it is worth absorbing to appreciate how these differences will manifest in historical GDP as well as future trends.

Not all capital stock is created equal: housing and infrastructure

Property and infrastructure share several common characteristics. They are (i) capital-intensive, featuring large upfront investments that (ii) typically generate low percentage returns on the upfront invested capital but (iii) over a very long useful life (50-100 years3).

With greenfield urban housing, the GDP impact is initially dominated by gross capital formation (“I”). When residents move into their newly built apartment, the incremental GDP impact (“R”), represented by actual or imputed rent, is modest — often representing low-single-digit percentage4 of the upfront capital investment. But these assets have very long useful lives (50 years or more) so if the asset is utilized (lived in), it eventually pays for itself (and more) in a long tail of future GDP.

Here is an illustrative example of what the GDP impact of housing might be:

In the illustrative example above, a $100,000 investment5 in newbuild construction starts to yield a small return (4%) after a three-year construction period. Over fifty years, the long tail of GDP consumption grows steadily. By year 50 (when it might need to be replaced), it is delivering a 19.5% real return annually on the original investment (driven by increases in real household income) and has generated >5x accumulated real returns on the original investment. This turned out to be a nice payback if one could be patient.

Infrastructure also tends to have the same characteristics; if anything it features even longer useful lives and even lower initial returns on equity. But similar to housing, if properly utilized, it will deliver a positive GDP return to society over many decades of use. This is especially true the more household incomes rise — this increases the real GDP return as these assets are “consumed” over time. All things equal, the value of shelter and infrastructure is higher for people as their incomes rise.

Not all capital stock is created equal: factory equipment

In contrast, industrial assets have much different characteristics. While there is a property or physical plant component to industrial investment, the majority of industrial assets are comprised of factory equipment.

This factory equipment tends to have shorter useful lives (3-12 years6) and much higher percentage returns on investment so that businesses can recover the value of their capital investments within that shorter useful life period. An illustrative model of GDP impact industrial equipment might look like this:

As you can see, the first notable difference is that the initial investment (the “I”) can happen quickly — with machines manufactured (or imported), delivered, installed and rapidly put to work to deliver incremental GDP return or growth (the “R”). This means less capital that is tied up in non-productive construction-in-progress and working capital. Second, the initial percentage returns on investment are much higher than housing and infrastructure — in this case, 20% per year.

But because the asset only has a useful life of 12 years, the lifetime GDP return is only 2.0x, lower than the housing example above. At that point, the asset will need to be replaced due to obsolescence or simply being worn out. One of the key takeaways here is that “lower RoI” housing and infrastructure is not necessarily worse than “higher RoI” business investment because of the differences in useful life.

A (much) longer-term view of the property transition

Using these illutrative frameworks for thinking about “R” and “I” in GDP terms, one can see how the economy has been making this transition over multiple years with the Q1 data simply another datapoint in a long series of datapoints confirming this trend.

“Three Red Lines” (3RL) in August 2020 was the beginning of the end for property and “old” infrastructure as leading drivers of the economy. But the transition started well before7; most people just didn’t notice.

The rise of newbuild housing and infrastructure were the principal components of the multi-decade “urbanization” uber-macro economic policy that really kicked off shortly after the post-reform period. It started to accelerate in the early 2000s as legislative reforms were enacted that enabled and formalized property ownership, a prerequisite to home ownership by households. And it really got a boost after the Global Financial Crisis in 2007-08 when authorities approved a massive stimulus to rapidly absorb millions of jobs (mostly migrant laborers) that were abruptly shed in the coastal export processing regions.

From the 2000s to the early 2010s, investment in property and infrastructure drove gross capital formation to hitherto unseen levels, high even by “East Asian development model” standards. But there was a notable change around 2013-14 when property investment as a percentage of GDP peaked. After plateauing for several years, triggered by 3RL in 2020, it began a steady decline. One of the best illustrations of this multi-decade cycle is illustrated in floor space completions8:

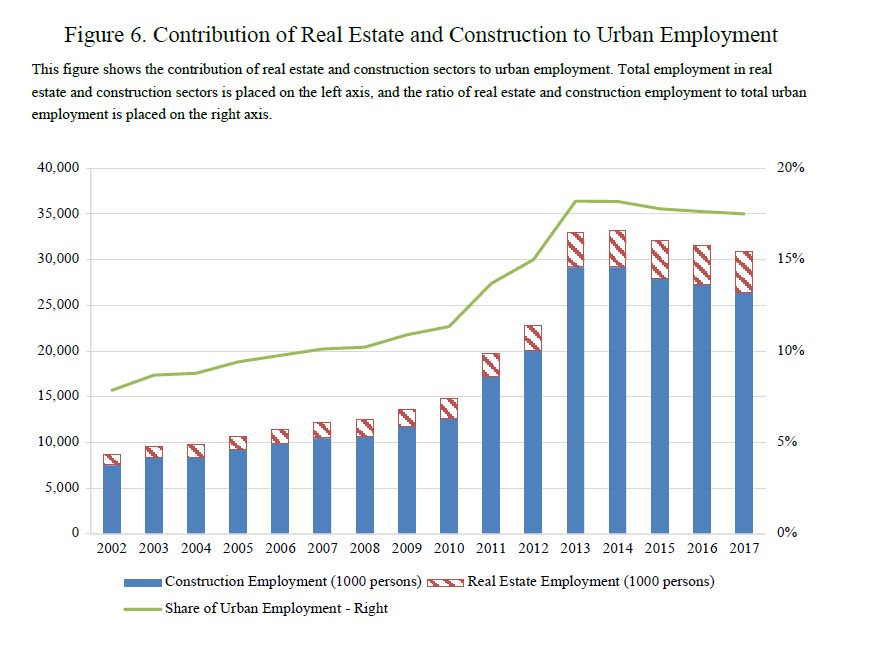

While it is a lagging indicator compared to starts and new sales, floorspace completions better correlates with the amount of economic resources — mainly blue-collar migrant labor — dedicated to the construction industry. This long-term chart illustrates the multi-decade rise, plateau and now decline9 in the amount of economic resources dedicated to residential housing, which accounts for 70-80% of total floorspace built. Other related metrics like construction employment and real estate employment also corroborate these long-term trends10.

Property and infrastructure suppressed GDP growth since 2010.

Among others, major SOE reforms in the 1990s (抓大放小 or “grasping the big, letting go of the small”) and China’s admission to the WTO in December 2001 set the stage for the heady days of double-digit annual GDP growth in the mid-2000s.

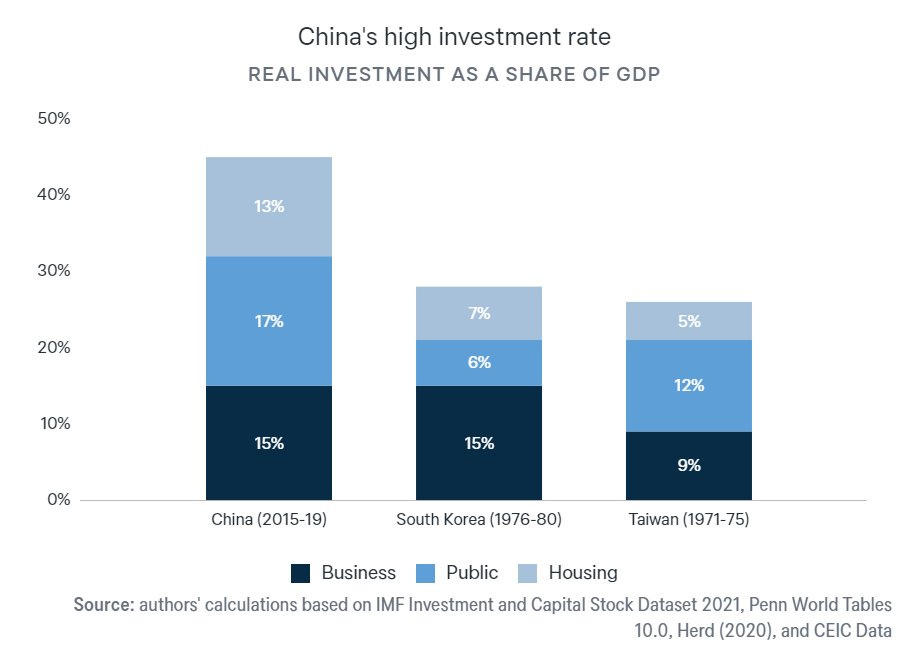

Much of this rapid growth was fueled by increasing investment in the business sector, and in particular the export processing industries in the coastal regions. In the charts below we can see how “business investment” (yellow line) rose from ~14% (of GDP) in the late 1990s to a peak of ~22% around 2010.

The Global Financial Crisis hit the export processing sector hard. Virtually overnight, millions of factory workers were unemployed as thousands of factories shut in the Pearl and Yangtze River Deltas. In crisis mode, authorities rapidly approved the largest-ever stimulus plan in Chinese history, authorizing ¥4 trillion of funds in November 2008. These funds flowed through local governments into the property and infrastructure construction.

We can see this in the blue and orange lines above, representing housing and infrastructure investment. From a combined ~15% in the mid-2000s, housing and infrastructure investment nearly doubled to ~28% of GDP by 2016.

These stimulus funds supported GDP growth in the post-GFC period. Without these funds, all of the laid-off workers would not have been able to find work and GDP would have dropped significantly. Instead, by mid-2009, GDP growth had recovered back to nearly 10% again.

While I agree that the 2008-09 Chinese economic stimulus plan supported growth and prevented mass unemployment in the immediate aftermath of the GFC, continued investment in housing and infrastructure ended up lowering aggregate GDP growth from the average rate of ~10% from 2000 to 2011 to ~6% from 2012 to 2023.

This relates back to the mechanics of housing and infrastructure investment described above. The low RoI nature (offset by very long useful lives) of housing and infrastructure investment meant that GDP growth necessarily had to slow down once the investment in these asset classes plateaued around 2012-13. This is just an arithmetic reality when you essentially “crowd out” business investment that regularly generates >20% RoI with housing and infrastructure investment that initially yields returns in the low single-digits.

The offset to lower GDP (a flow concept) was rapid accumulation in capital stock that sits on the national balance sheet (a stock concept). In effect, while GDP slowed down, Chinese people were benefiting from rapidly improving quality and amounts of living space paired with improved public infrastructure like modern highways, metro systems, high-speed rail and airports. If you really think about it, households were the ultimate beneficiaries of all of this housing and infrastructure spending.

Today’s shift from property and infrastructure investment to manufacturing boosts GDP growth

If the shift from high-RoI business investment to low-RoI housing and infrastructure investment in the 2010s suppressed GDP growth, a reversal of that shift should have an opposite effect i.e. boost growth. Surprisingly robust GDP growth numbers, particularly over the last two quarters, may be indicators of this trend.

Every resource (again, we are mainly talking about labor) that shifts from mature “Pareto-optimal” sectors like residential housing and LGFV-funded local infrastructure to “Pareto-improvement” sectors like electric vehicles or clean energy infrastructure represents a boost in RoI.

As the net impact of these resource shifts accumulate, the higher GDP return will build up and should have a boosting effect on GDP growth. Instead of investments in residential housing that only yield 3 to 4% incremental housing consumption the following years, each investment in a new Gigafactory could yield 80%+ returns11 on GDP investment.

I call these advanced manufacturing industries “Productivity Kings” because they leverage R&D and high-value capex to drive production efficiencies that are not only captured by their employees (wage and personnel growth) and capital holders (increases in net profit) but also even more significantly, large consumer surplus that all of society benefits from. That electric vehicles are now just as affordable (relative to average incomes) for Chinese people as they are for rich countries shows how much impact companies like BYD have had on the economy and not just for their shareholders.

Getting the hard part out of the way

Like China, South Korea and Taiwan also underwent rapid urbanization from the 1960s through the 1990s.

The two “East Asian Tigers” also relied fairly heavily on investments during their rapid urbanization phases. South Korea made large business investments (e.g. heavy industries like chemicals, steel and shipbuilding) and Taiwan made large public infrastructure investments to support their small and medium family-run entrepreneurial businesses.

However, China pushed the investment-centric economic development model even farther, investing heavily in housing, public infrastructure and business all at the same time.

Now we know that South Korea and Taiwan were probably the two most successful economic development stories in the 20th century, as I describe in one of my favorite early writings in 2015 “What are the most fascinating stories of nations that went from poor to rich?”

Does China stretching the investment-centric development model take it one step too far? I do not think anyone can say for certain because it will depend entirely on how well these built-up housing and infrastructure assets sitting on the balance sheet perform over the next 50-100 years of their useful lives. Nobody has a crystal ball that can tell you how those housing blocks in Changsha will be utilized between now and the 2070s.

However, what I can say with a high degree of confidence today is that China has better housing and infrastructure than South Korea and Taiwan did when they were at similar stages of economic development. All of that housing and infrastructure investment enable the average Chinese person to enjoy higher quality modern housing and better infrastructure than the average Taiwanese person in the 1980s or Korean person in the 1990s.

I can attest to this, having spent an aggregate of three years living in Taiwan over the last decade. Taiwanese authorities decided to eschew large and fancy housing as a matter of policy under the 1990s after Martial Law ended. The net result is that today, many parts of Taipei are still fairly “shabby” (at least on the exterior) and most homes are quite small. I biked around Taipei during the 2021 lockdown and these photos are quite representative of the typical neighborhoods.

In a sense, one can actually view heavy investments in housing and infrastructure as fundamentally aimed to benefit households. They represent consumption choices. Much of that consumption is deferred (because of the long useful life) but it does not change how it is fundamentally a consumption-oriented policy choice.

Beijing’s multi-decade urbanization policy and its large emphasis on low RoI housing and infrastructure investment represented sacrificing near and medium-term GDP growth for the future consumption as these assets rise in value with household incomes decades in the future benefiting multiple generations. In effect, for those who tend to focus heavily on GDP, it got “the hard part out of the way” and now the economy can focus on putting more resources to work in more “exciting” higher-RoI activities like advanced manufacturing and high-tech services that are critical to fully developing such a large economy.

Section 1 is about agricultural production but I do not think items like the “output of milk” (apologies in advance to 蒙牛 Mengniu Dairy) are all that important to pay attention to at this phase in China’s economic development.

As discussed here, FAI data can be problematic, particularly when trying to match up with gross capital formation, but for trending purposes it is still useful.

In the United States, we are still using train track built more than 150 years ago to carry bulk freight thousands of miles across the country. I live in a building in Lower Manhattan that was built more than a century ago.

In China, with upwards of 90% of apartments owner-occupied, imputed rent is the primary determinant of the housing component of consumption in GDP. Chinese GDP accountants are notably conservative in how they calculate imputed rent.

The land component of newbuild construction is not considered gross capital formation, although the sale of the land use right itself does lead to fiscal spending by local governments.

BYD’s accountants use a depreciable life of 3-12 years for its “machinery and equipment” which make up the bulk of its fixed assets.

Here I argue that the property transition really started with the anti-corruption campaigns following the 18th National Congress in 2012. Rooting out entrenched corruption (particularly at the local level) was arguably the most important first step to be able to enact necessary policy reforms to shift the economy away from property and infrastructure.

While others often focus on sales or starts, I like completions because while it is a lagging indicator, it also cuts out a lot of the noise. Because it is based on completed floorspace, it better correlates with GDP than say, starts, which may or may not be completed, especially as developers were motivated to increasingly collect deposits from potential buyers farther in advance over time.

Especially when viewed from a percentage of GDP perspective i.e. relative to growth in the rest of the economy.

Source: Rogoff & Yang (2020) “Peak China Housing” Figure 6. Contribution of Real Estate and Construction to Urban Employment.

GDP return on investment is calculated differenly from typical financial returns on investment. Notably, it adds back depreciation and staff/employee costs. For example, here I calculated that BYD generated a financial return on equity of 14.5% in 2022, but its GDP return on asset investment is more than 80%. BYD is one of the better Chinese companies though and most manufacturing companies cannot achieve those levels of return.

Your description of the fundamental different return characteristics of housing/infrastructure vs industry is valuable, showing in principle what have been and may well be the consequences of the 3RL and advanced manufacturing foci.

I do wonder if GDP is a red herring. For example, not only are nations' GDP wildly incomparable, but due to differing methodologies even deltas from year to year. To cap it all, I wonder if the Dungeon Master, whom evidence would suggest cares far more about substance than form, cares much about such numbers in reality:

1) I haven't looked if it is still the case, but according to https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/758065.shtml the "accounting" of relevant GDP and the resulting annual changes must be miles apart from the (sensible, I might add) "DCF" type proforma in your article:

"Chinese statistics have significantly underestimated housing consumption including rentals, utility and decoration expenditures. Rentals include actual rents paid by tenants and more importantly, imputed rents for owner-occupied homes. In practice, calculating imputed rent is not an easy task. China's statistics bureau uses construction costs multiplied by a fixed depreciation rate for a rough estimate. While this method is easy to employ, it greatly underestimates actual housing consumption. For starters, construction costs, which do not even include land costs, greatly underestimate the market value of housing, and the 2 percent depreciation rate applied for urban housing also underestimates the rental rate of return."

2) Again I am unsure if it is still the case, but https://web.archive.org/web/20200321163609/http://jedsnet.com/journals/jeds/Vol_3_No_3_September_2015/6.pdf suggests Japan's imputed rent, important given high home ownership in both countries, was circa 20x China's on a per square meter basis.

3) We don't really have the all important housing/infrasturcture and indeed industrial ROI figures, but directionally, isn't going after "new quality productive forces" a no-brainer? What other (sensible) direction exists in the value chain? More importantly, doesn't it look remarkably like checkmate?

Finally, why wouldn't China want to forever remain a "developing country"? ;-)

Just wanted to say I really enjoy your writing and analysis. Your work on LGFVs in particular was quite eye opening and provided a lot of nuances. The relation between abstract economic statistics and peoples' lived experiences is of course also highly dependent on all of the history that led up to that point, however in today's world of oversimplified metrics (and "influencers" who create even more oversimplified lists and explainers") this type of analysis can fall by the wayside. The goal of economic development should be improving people's lives, paper accounting can only tell so much of the story.

On an amusing side note, I have noticed while the initial tone of your articles was quite conciliatory to the "China watchers" (cough, Pettis, cough) now you are starting to realize that for the most part, none of them are not quite as "rational" and "non-ideological" as they make out. I think in one of your recent threads you became more acerbic and I'm here for it as these people deserve ruthless criticism. Keep up the great work.