Will China become old before it becomes rich?

It could go either way

The Economist: China’s Achilles Heel

LIKE the hero of “The Iliad”, China can seem invincible. In 2010 it overtook America in terms of manufactured output, energy use and car sales. Its military spending has been growing in nominal terms by an average of 16% each year for the past 20 years. According to the IMF, China will overtake America as the world's largest economy (at purchasing-power parity) in 2017. But when Thetis, Achilles's mother, dipped her baby in the river Styx to give him the gift of invulnerability, she had to hold him somewhere. Alongside the other many problems it faces, China too has its deadly point of unseen weakness: demography.

CNBC: China will get old well before it gets rich

As the massive demographic dividend that propelled China’s economy forward has come to an end, the country faces the unfortunate implications of its one-child policy. Whether the economic power China has accumulated over the last thirty years will be adequate to fund its growing pension and healthcare costs may be one of the most important questions policy makers in China must wrestle with and resolve.

In the short-term, the country’s demographic realities will create opportunities for international senior care and healthcare operators; however, in the mid-to-long term the ability to view China as a market for products and services may hinge on the country developing an alternative economic model that successfully takes advantage of more than a low-cost workforce.

Whether the country’s central planners have tools at their disposal to design such an option remains to be seen.

Defining “Old” and “Rich”

First, one needs to define what it means for a country to be “rich”. Fortunately, the World Bank does most of the work for us as it has broken down the world’s countries into various groups by income level. At the very top of the list are “high income” countries and the latest cut-off point to join this club is around $13,000 in nominal per capita GDP. This is where countries such as Argentina and Chile currently sit. Today, China’s nominal per capita GDP is approximately $8,000.

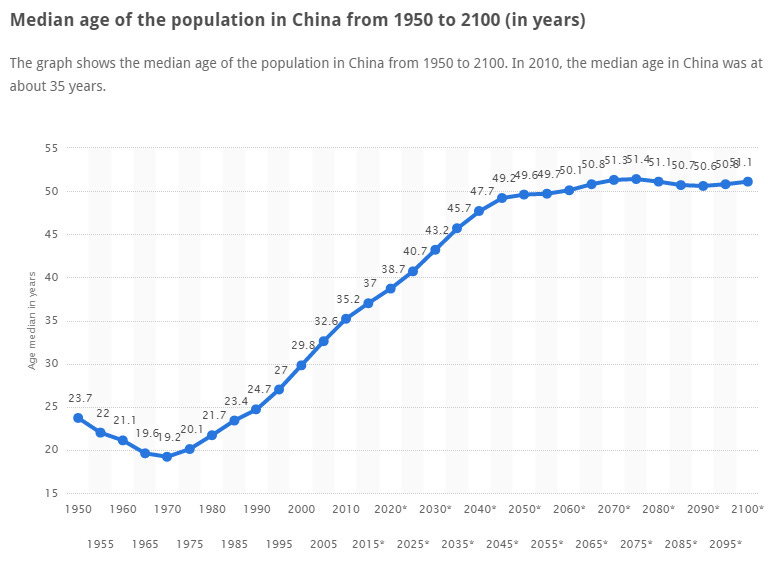

Second, we need to define what it means for a country to be “old”. There aren’t any hard definitions for this but I know as an example that Japan (median age: 46) is considered “very old” while most European countries are also considered “old” (median ages: early 40s). This suggests that being “old” means a country’s median age has surpassed 40, or right where South Korea sits today. China’s current median age is 36.7.

Now let’s do a little forecasting and simple math to see where we come out.

I’ll start with China’s median age forecast because there is less forecasting uncertainty around demographics. According to this forecast, China’s median age will surpass 40 sometime around 2025:

With this date of 2025 in mind, we can answer this question with simple arithmetic. The implication here is that in order for China to reach “high income” status by the middle of the next decade, it will need to grow its per capita GDP approximately 5% faster per annum than the group of wealthy countries. That means if “high income” countries as a group grow by 1% per annum, China will have to grow at 6% a year for the next decade to catch up [1]. If you extend the deadline out to 2030, then China only needs to grow 3.5% faster per annum to make it.

So this question really comes down to whether China will be able to pull this off. Today, Chinese policymakers face the difficult task of re-balancing the economy and there is obviously a lot of work still yet to do there. So while reaching “high income” status by 2025 or 2030 is certainly possible, I would say that there is at least an equal probability of not reaching it in which case they would have “gotten old before they got rich”.

It’s worth noting that many parts of China would already be considered “high income” by the World Bank or are close to hitting that mark. Around 40% of China’s population lives in provinces that have nominal per capita GDP north of $10,000. These are predominantly the wealthier provinces that straddle China’s coastline such as Guangdong, Fujian, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Shandong. Each of these provinces are larger than most countries. For example, Guangdong Province on its own is quite comparable to Mexico — the world’s 15th-largest economy and 11th-most populous.

The long-term impact of the Cultural Revolution

There’s also another factor that’s also worth discussing.

The phrase “China will be old before it becomes rich” comes from the idea — informed by past experience, particularly Japan’s — that as a country ages, its growth slows dramatically. Some take this to mean that if China does not become a rich country before it becomes old, it may never achieve it at all …

However, China does have one relatively unique historical element that may to a certain extent mitigate or postpone the economic effects of aging by a few years. This has to do with the Cultural Revolution.

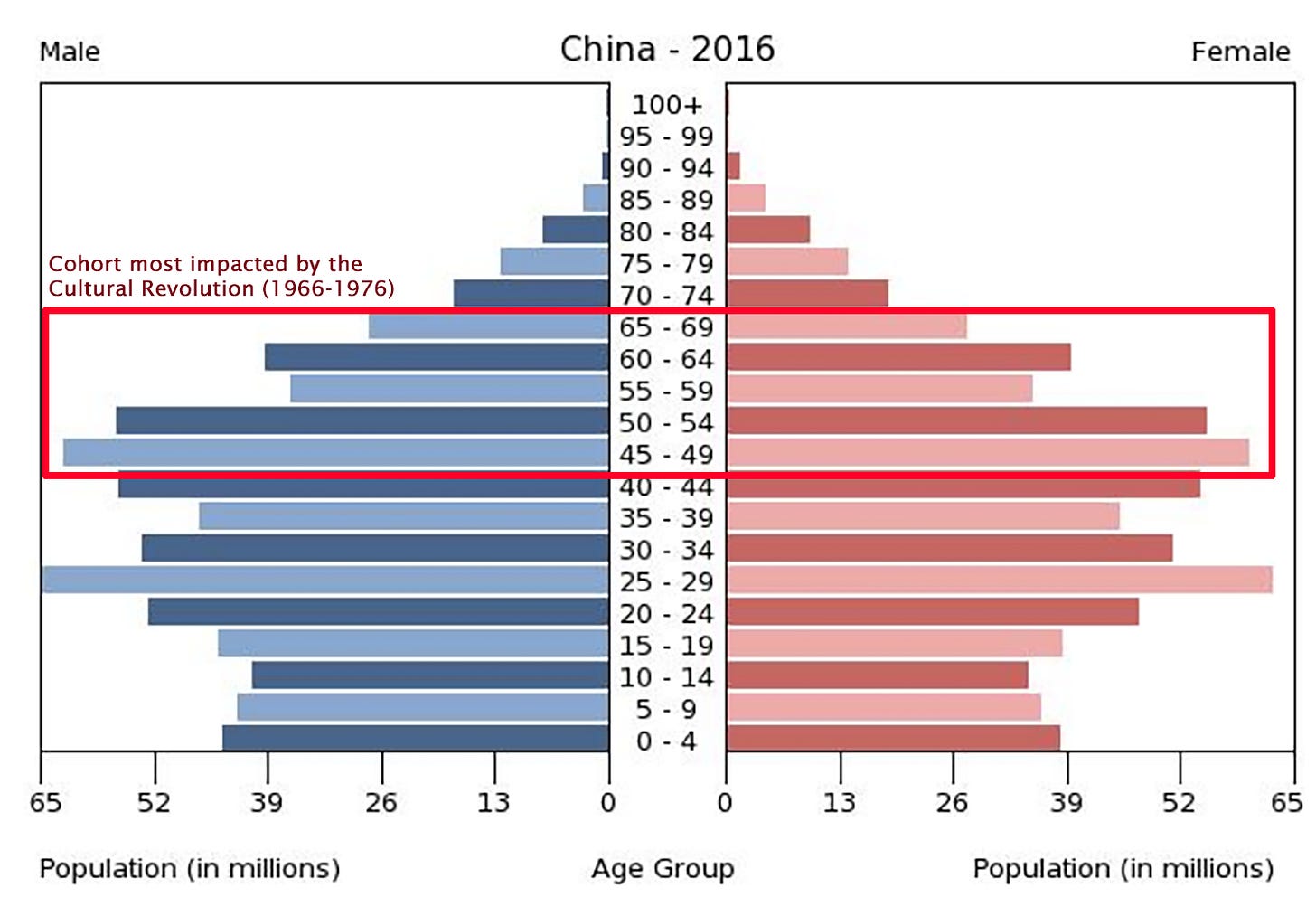

Many terrible things happened during the Cultural Revolution, but perhaps the worst (at least from a long-term economic perspective) was the wholesale closure of schools and universities for an entire decade from 1966 to 1976. This tragic event prevented an entire generation of Chinese from receiving a full education and negatively impacted this cohort’s collective ability to achieve its full potential [2].

This cohort happens to be the one that is now entering retirement age.

A 65-year old person in China today (2016) was born sometime in 1950–1951, which means that from the ages of 14 to 24 they basically had no access to a formal education. Now imagine how different your life would be if you had missed high school and college and instead worked the land out in the middle of nowhere for most of your youth.

These new retirees are being replaced in the workforce by young adults born in the 1990s who have grown up in a relatively prosperous China, received a full modern education and have had access to and are familiar with the latest technologies and amenities of the modern world. The productivity differential between them and the retirees is quite large, especially if you consider the types of skills you need in an advanced “post-industrial” economy. And this differential goes a long way to potentially blunt the demographic effects of a situation where one and a half people retire for every new person entering the workforce.

And while every developed country experiences this to a certain extent (i.e. the current generation of young workers being more educated than the latest generation of retirees) the ravages of the Cultural Revolution amplified this effect for China.

So as it relates to this question, the implication of all of this is that China’s looming demographic decline may have less of an impact than the experience of others, at least until the scar tissue from the Cultural Revolution I described above completes its demographic journey through the system.

This effect will start to wane in the late 2020s.

Notes

[1] Note that because we are looking at nominal GDP figures, part of this growth can be driven by the appreciation of the Renminbi against the U.S. Dollar.

[2] I use the word “collective” because at an individual level, many of China’s most successful entrepreneurs today belong the generation most impacted by the Cultural Revolution as youths. Clearly a formal education isn’t the sole determinant of success. For this generation, the economic opportunities made possible by three plus decades of relentless growth trumped any lack of formal education. Also if you really think about it, the fact that the country achieved so much in spite of (and so soon after) the ravages of the Cultural Revolution is nothing short of impressive.

This was originally published in Quora in January 2016.