Maslow’s Hammer: Tyranny of the Accounting Identity, Part I

Origins of a fundamental Chinese economic axiom

One of the prevailing narratives about China’s economy nowadays centers on the perception that it “consumes too little and saves too much”, coupled with its GDP accounting identity dyad, the belief that it “invests too much”. This viewpoint has penetrated mainstream thought to such an extent that it is considered by many to be a fundamental, almost sacred, axiom of the modern Chinese economy.

This recent Project Syndicate article was another in a string of pieces adopting this narrative:

Household consumption typically accounts for 60% of a country’s GDP. For the 2011-20 period, it was 68% in the United States, 59% in India, and 61% in middle-income countries excluding China, where it was only 37%. While China accounted for 16.7% of global GDP between 2017 and 2021, its share of global household consumption was a mere 11.5% …

Here is another one from the recent FT article “China after the property boom”:

Given the relatively modest role that consumption plays in its economy, the IMF has described China has a “global outlier”. The country’s gross domestic savings as a percentage of GDP is 44 per cent, compared with an average of 22.5 per cent among OECD members. Over the long term, much of this is believed to be precautionary savings, cash put aside for housing, education, healthcare and retirement.

In tracing the origins of China’s “exceptionally high savings and low consumption” rate today, the IMF notes “inadequate social spending” as well as earlier changes such as the one-child policy and the “gradual dismantling of the social safety net” in the 1980s and 1990s.

These articles, and countless others like it, all play on some variation of themes related to this narrative:

China’s growth model is imbalanced with too much investment and not enough consumption. This was made possible primarily by subsidies to investment and production activities and is the main reason for its “weak household demand”.

Over-investment leads to an increasing proportion of non-productive projects and large, “systemic” misallocation of capital that will accumulate until investment rates fall significantly.

China has been able to continue over-investing by taking on increasing amounts of debt. This is not sustainable and when China runs out of debt capacity, it will be “forced to adjust”.

Chinese policymakers are following this path because they target GDP growth rates that are above sustainable levels, as the party’s political legitimacy depends on high growth. This makes it “politically difficult” to change.

In many discussions about China’s economy today it is hard to avoid this narrative and I often wonder if those that reference it truly understand the narrative’s intellectual foundation and historical origins. This is not just a petty academic debate but one with significant real-world impact. As I describe in my ongoing series on LGFVs, there are major reforms needed that will have long-term impacts on billions of people around the planet. Getting the framing correct and formulating the right policy prescriptives are extremely important.

In this first part of this multi-part essay series, I will explore the historical underpinnings and development of this narrative. Most of this is just review for anyone who has been part of the Chinese economic debate for a reasonable amount of time. I will probably get a few things wrong and welcome feedback and criticism on the characterization of the thesis. This background is important to set a common baseline understanding that will be referenced in follow-on essays in this series.

Let’s Get Technical

Economics can be a rather technical subject, characterized by abundant use of domain-specific vocabulary. It frequently delves into references from obscure historical periods and encompasses a wide array of academic theories and “isms”. I took my first economics class at a pre-college program in 1995, later matriculated at the same university and eventually graduated with a B.S. in Economics.

However, I would by no means consider myself an economist1. Although I retained some concepts from my college courses, fully delving into the Over-Investment Thesis necessitated conducting more in-depth refreshers on the subject, including going beyond just academics and tying it to the what I had learned in the real world, particularly my experiences living and working in the Greater China region over many years.

Calculating Gross Domestic Product

International economics is a sub-category that deals with, among many other things, the intricacies of measuring economic activity across different economies. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is one of its more important metrics and sits at the heart of the “Over-investment Thesis”. Understanding this narrative requires a technical understanding of how GDP is calculated/interpreted that is not typically well-understood by the average layperson.

GDP is the measure of economic activity within some defined geographic region, typically a country, over a specified period of time. It is calculated by accountants pulling together various data series and making adjustments/estimates while trying their best to adhere to evolving global GDP accounting standards.

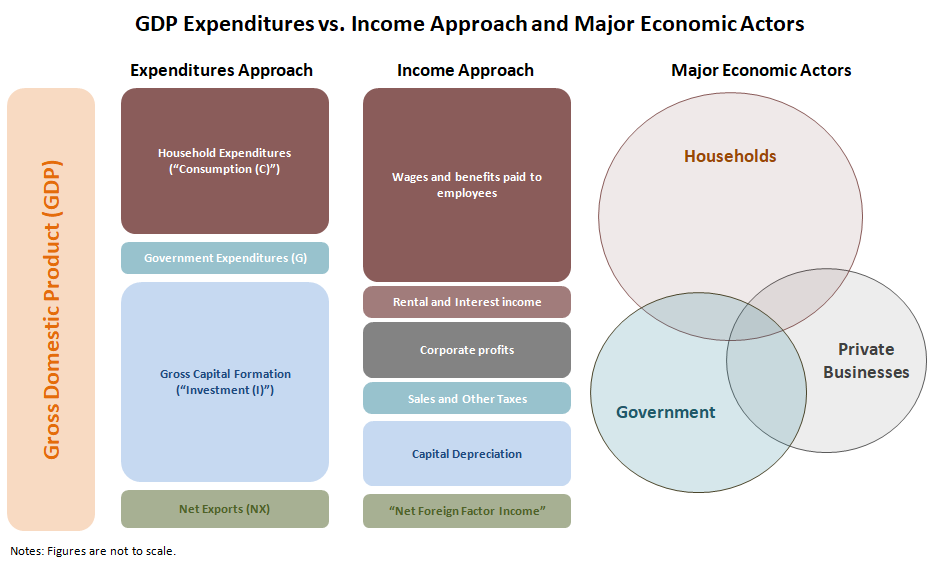

There are multiple ways of calculating GDP. The first is called the “Income Approach”. Under this approach, accountants count all of the labor and capital used in the production of goods and services in a certain period. The second is called the “Expenditures Approach”. Under this approach, accountants tally the sum of “final” goods and services purchased in the economy over a certain period by consumers and the government as well as net import/export balances.

In practice, accountants are not counting every single transaction that takes place. Instead, they rely on existing data series (like tax receipts) and supplement with surveys taken across a representative subset of the population. Economists then apply judgment, making estimates and adjustments to the data. This is why the first GDP numbers you see are estimates that get “firmed up” as data from more series comes in over time.

The less developed an economy, the larger the informal economy and the more economists must rely on adjustments and estimates. GDP can also be a highly political number, which creates its own set of issues. In the United States, the expenditures approach is considered to be the more accurate way of estimating GDP than the income approach2. Ultimately both approaches are used to triangulate to the final numbers.

The GDP Accounting Identity

One of the fundamental formulas describing GDP is from the expenditures approach:

GDP = Consumption (C) + Government (G) + Investment (I) + Net Exports (NX)

This formula is referred to as the “National Income Identity”3. Consumption (C) (a.k.a. “Household Expenditures”) consists of spending by the private sector and Government (G) comprises expenditures of the various levels. Investment (I), also known as “Gross Capital Formation”, is comprised of fixed assets and working capital items like inventory — final spending that is capitalized and ends up on the official national balance sheet in the form of “Capital Stock”. Net Exports (NX) is Exports less Imports.

A derivative formula creates what is known as the “Saving-Investment balance”4:

Savings (S) = Investment (I) + Net Exports (NX)

Here, Savings (S) refers to the savings of both the government and household sectors. For economies that have a neutral trade balance (Net Exports = 0), Savings (S) must equal Investment (I).

Note: in this essay series, to distinguish between technical GDP accounting and colloquial “layperson” definitions, I will generally refer to the technical definitions as “Consumption (C)”, “Investment (I)”, and “Government Expenditures (G)” and the colloquial definitions as “consumption”, “investment”, and “government”.

The Over-Investment Thesis

Much credit should be given to Michael Pettis, a finance professor at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, as one of the main advocates of this “Over-Investment Thesis”. Through the years he has been remarkable in his consistency and adherence to both writing and promoting this narrative.

I first came across Michael’s writings in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”). I enjoyed reading his long e-mail letters where he deftly weaved together economic topics and historical examples with the then-current Chinese economy that was going through significant change.

He has been writing about China’s propensity to over-invest for almost two decades now. In October 2009, he wrote:

Consumption growth in any country is necessarily limited by the growth in household income and wealth, neither of which has grown nearly as rapidly in China as the country’s economy. China’s development model is a steroid-fueled version of the classic export-led model common to many high-saving Asian countries. This model involves systematically subsidizing production and investment, often leading to very inefficient investment.

In his 2013 book The Great Rebalancing, he wrote:

… but with consumption so low, it would mean that China was overly reliant for growth on two sources of demand that were unsustainable and hard to control. Only by shifting to higher domestic consumption could the country reduce its vulnerability and ensure continued rapid growth. This is why in 2005, which household consumption at a shockingly low 40 percent of GDP, Beijing announced its resolve to rebalance the economy towards a greater consumption share.

How GDP accounting identities explained the Chinese economy

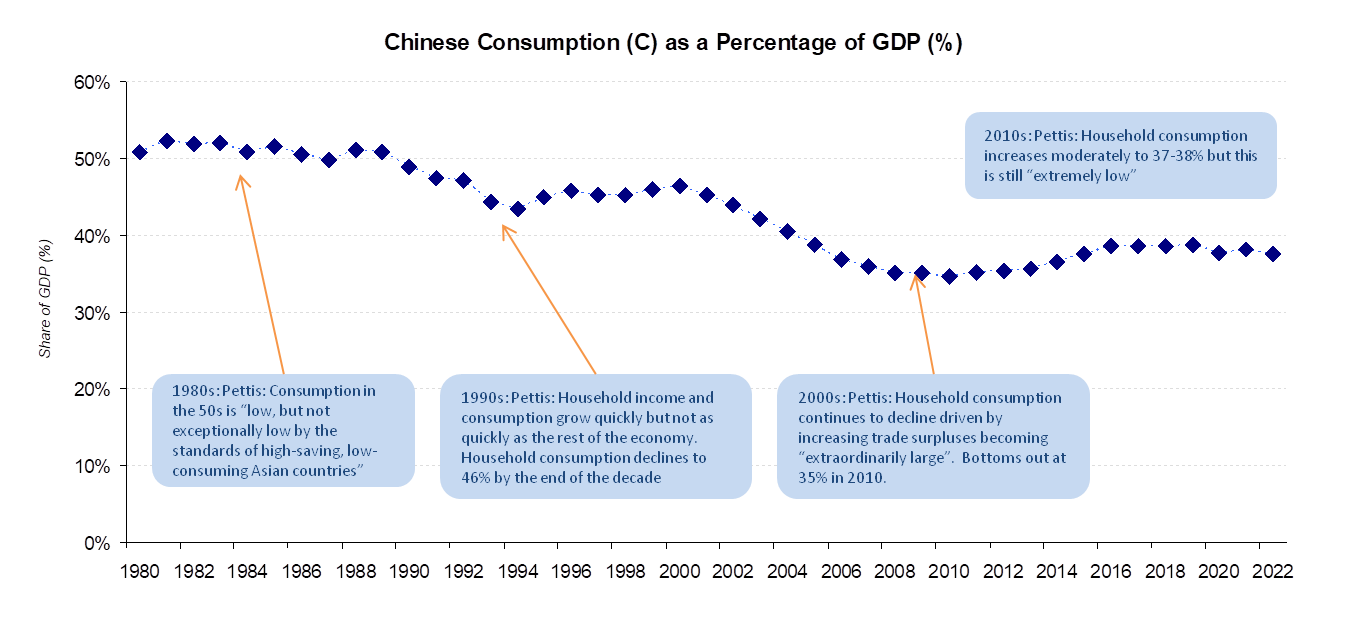

The GDP accounting identities lay at the heart of the Over-Investment Thesis and narrative. As Michael explains in this 2011 paper, in the 1980s after China’s reform and opening up, “household consumption comprised 50-52% of China’s GDP”. During the 1990s, both household income and Consumption (C) grew quickly, but “not as quickly as China’s economy”. This resulted in a sharp decline in Consumption (C) to the mid-45s. But in the 2000s, it started to drop to levels that were “unprecedented in history for a large economy in times of peace.” It dropped to 36% on the eve of the Great Financial Crisis and then dropped even further, bottoming out at below 35% in 2010:

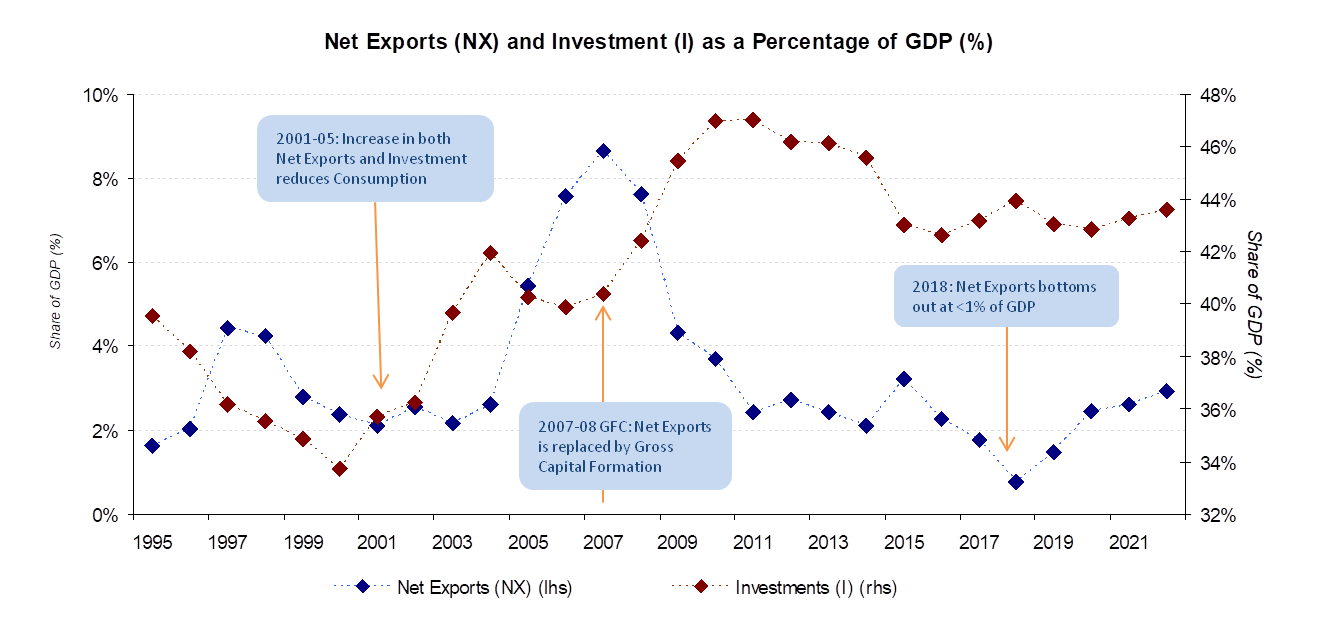

Michael almost always explains this historical trend through the lens of the GDP accounting identity. The rise of China’s export-led industrialization growth model in the coastal regions of the Pearl and Yangtze River deltas led to rapidly rising Net Exports (NX), peaking at 8.7% in 2007 “far surpassing the trade surpluses Japan generated in the late 1980s”. This contributed to global trade imbalances that led to the GFC and was ultimately unsustainable. And indeed it was — over the subsequent decade, Net Exports (NX) would decline, bottoming out at 0.8% in 2018.

With such a large part of the economy in decline, how could China keep up its high growth rates? For the better part of the 2000s, rising exports had helped drive double-digit growth rates, topping out at a whopping 14% in 2007. But in a post-GFC trade environment, the Chinese economy was forced to replace sharply declining net exports with domestic investment. You can see in the above chart how starting in 2008, Net Exports (NX) and Investment (I) flipped. This caused Consumption (C) to bottom out at 34.6% in 2010.

“The end of the growth model”: Imbalances and unsustainable growth

It is understandable why trade imbalances were unsustainable. A large trade imbalance means that you are exchanging goods and services with the world in exchange for foreign assets.

In 2016, Warren Buffett explained the dangers of high trade deficits from the American perspective in the allegory of Thriftville vs. Squanderville:

In effect, our country has been behaving like an extraordinarily rich family that possesses an immense farm. In order to consume 4% more than we produce--that's the trade deficit--we have, day by day, been both selling pieces of the farm and increasing the mortgage on what we still own.

To put the $2.5 trillion of net foreign ownership in perspective, contrast it with the $12 trillion value of publicly owned U.S. stocks or the equal amount of U.S. residential real estate or what I would estimate as a grand total of $50 trillion in national wealth. Those comparisons show that what's already been transferred abroad is meaningful--in the area, for example, of 5% of our national wealth.

While China did not run the highest trade imbalances in percentage or per capita terms, the sheer scale of its population meant that it would have enormous impact on global trade that would likely result in enormous trade frictions. Different from others like Japan, which could ride the export-oriented industrialization wave to becoming advanced economies, this strategy was simply not possible for China and its then-1.2B+ population5. It had to find a new growth model to continue its economic ascent.

On November 9th, 2008, China unveiled a ¥4 trillion economic stimulus package to offset the impact of the GFC and millions of suddenly-unemployed workers in its coastal export regions. It was the largest such stimulus that had ever been put in place in the country, equivalent to almost 12% of China’s then-GDP. Much of it went to “fast track” domestic infrastructure and construction projects that were already in the planning phase. Millions of migrant workers simply moved from shuttered export factories in Shenzhen to construction sites in places like Wuhan and Guiyang. The GFC and resulting stimulus plan ushered in the global unveiling of China’s new primary growth model: domestic investment.

But according to Michael, there was a big problem. Similar to how trade imbalances were unsustainable in driving growth in the long run, he argued that the surge in domestic investment was also unsustainable. To him, these were fundamentally the same underlying models — and similarly unsustainable. As he wrote in “The end of the growth model” in 2011:

It is increasingly obvious that China has reached both constraints. The global financial crisis has eliminated the ability of the rest of the world to absorb China’s large trade surpluses, and capital misallocation has been a serious problem for much of the decade …

… if capital misallocation is becoming a problem, clearly China must make a major transition to a different growth model—one that allows household wealth and consumption to catch up with the enormous wealth generated in the past three decades so as to become an increasingly important driver of growth.

From unsustainable trade surpluses to unsustainable domestic investment

The case for why high trade surpluses were unsustainable was quite reasonable; in any case, the aftermath of the GFC proved this out. But (at least to me) it was less obvious why elevated domestic investment was an unsustainable growth model sitting there watching this unfold in 2009.

Pettis explains why by bringing up examples from history:

But historical precedent also makes it clear how powerfully addictive that model is. It is hard to find a single example of a country adjusting smoothly and quickly from a period of excessive investment-driven growth—just look at the United States in the 1930s, Brazil and Venezuela in the 1980s, the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1980s, Japan in the 1990s, and the Asian Tigers after 1997. In ever single case excessive debt led to a sharp growth contraction and a “lost” decade or two.

Up to this point, I had generally nodded along to his explanation of the global economy, particularly the risks and distortions of large global trade imbalances and some of the mechanisms like financial repression suppressing Chinese household income. But this is where the views began to diverge.

It all revolves around consumption

For Pettis, the switchover from growth enabled by unsustainable increases in the trade surplus to domestic investment was merely a symptom of the underlying root cause — under-consumption. Because of the GDP accounting identity, whether it was high Investment (I) or high Net Exports (NX) — or both — the offsetting effect was low Consumption (C).

The root of the problem, in his view, is the idea that the household sector is repressed by “politically entrenched Chinese elites” (defined somewhat vaguely) that “distort the Chinese economy by strangling purchasing power and subsidizing production at the expense of consumption.”6

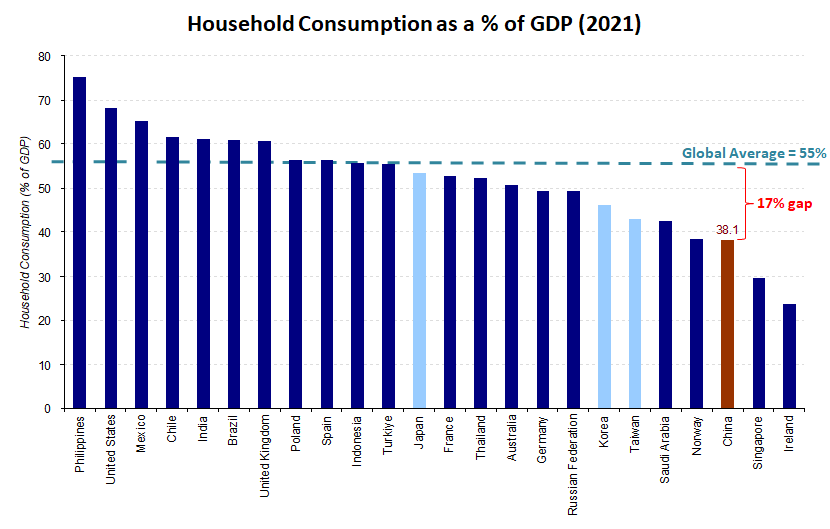

Michael goes on further to say that China has the most extreme levels of under-consumption in modern history, often sparing no hyperbole in descriptives. In the chart below, we can see how China at 38% is 17% below the global average and only ahead of trading entrepôts like Singapore and Ireland that are not comparable and suffer from their own distortions. China’s “extremely low consumption rate” provides overwhelming evidence of this imbalance and a growth model that is not sustainable unless it reverts to the mean.

Ultimately, the picture that Michael Pettis has consistently painted is of a China that is trapped in this low-consumption, high-investment model, ostensibly because entrenched interests have tied themselves to the model and make it “nearly impossible” to adjust. It has resulted in “massive misallocation of resources” and “spiraling debts”. Like every other “economic miracle” its growth story is coming to an end. His outlook is grim, and yours should be too.

“To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail” — Charlie Munger by way of Abraham Maslow

From Mungerism to Maslow’s Hammer

Charlie Munger, Vice-Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, is well-known for his multi-disciplinary thinking and liked to use the phrase, “To the man with only a hammer, every problem looks like a nail”. Originally, I had thought this was just another Mungerism but turns out it is officially attributable to psychologist Abraham Maslow, of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs fame.

Maslow’s Hammer is the idea that to specialists in their field, everything looks the same. For many economists and analysts looking at China, this GDP accounting identity has become that type of hammer. The tool can be useful in some situations. But to view an economy as large and complex as China through this lens can turn into a crutch. Especially if the tool itself is not as robust as it seems once you start poking into its fundamental logic.

The purpose of this essay series is an attempt to explain why we need to move on from Maslow’s Hammer and advance the collective understanding of how the Chinese economy works at a more detailed, granular level with a wider array of mental models and tools. In a follow-up essay, I will show how the core logic of the narrative — that China is under-consuming at an extreme degree — is at best, shaky.

Here’s a small preview: Chinese Consumption (C) is extremely low. But Chinese consumption is not particularly low at all.

Ultimately, understanding the differences between technical Consumption (C) and colloquial consumption is very important to figuring out what the GDP accounting identity numbers are really telling us.

My professional training was in finance, investing and as an operator and entrepreneur. I began my career in Asia and have continued to take a keen interest in this topic and this part of the world.

United States Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Concepts and Methods of the United States National Income and Product Accounts”

“Macroeconomics”, Auerbach and Kotlikoff (1998)

This is something I agree with. In his 2013 paper, on the subject of the relying on rising trade surpluses for growth, Michael wrote “The first constraint is usually a problem only for large economies, like the United States in the 1920s, Japan in the 1980s, and China today, whose trade surpluses are large relative to the rest of the world.”

“Trade Wars are Class Wars” (2020) p. 2

I think the biggest pitfall of an over-reliance on accounting identities to understand macroeconomics is the lack of causality inherent to using such a method. Pettis offers a useful framework for identifying the state of the global economy but it fails to account for agency on both sides of an economic interaction. His argument that "excess Chinese savings leads to higher debt in the US" is a good example. Not only is there high Chinese demand for assets like US treasuries, there is also an ample supply of US debt to make such a dynamic possible. Who or what is driving that supply-demand dynamic? My superficial understanding of one component of his argument is that the open capital accounts of Anglosphere countries (USA, UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand) is sufficient to attract inbound foreign investment. But, to borrow the Buffet analogy, actors in these countries choose to "mortgage" their farms as a result of their own economic conditions. There are two sides to the interaction! IE it seems odd to laypeople like myself to attribute the GFC entirely to global imbalances caused by excess savings in China.

Would note that both Buffet and Pettis prescription of some kind of "tariff" for foreigners owning US assets seems like an interesting, frictionless way to improve US domestic manufacturing and reduce our debt — without relying on massive spending bills like the IRA and CHIPS act.

https://carnegieendowment.org/chinafinancialmarkets/79641

Every time I read your articles I found that your opinions are always different from mainstream opinion. That makes me with little knowledge about economics feels like a jungle I’d like to see.