Project Finance with Kweichow Characteristics

Understanding China's land-centric financing approach and its role in infrastructure investment & poverty alleviation

Recently, there has been much attention on the growing pile of debt sitting on the balance sheets of provincial and local governments in China, particularly in some of its less prosperous provinces. Last month, the Wall Street Journal wrote:

One of China’s poorest provinces is testing Beijing’s mettle with a mountain of debt that local borrowers are struggling to repay. Investors worry it is a harbinger of another major debt crisis in the country, and believe the central government will have no choice but to defuse it.

Cracks have been showing in the finances of Guizhou, a southwestern province with jaw-dropping landscapes and some of the world’s highest bridges. It was one of China’s fastest-growing local economies over the past decade — thanks in large part to its heavy spending on infrastructure development.

I have come across a significant amount of flawed analysis, largely stemming from incomplete understandings of the workings of the Chinese financial system. Analyzing China through an American lens poses a challenge as the country operates very differently for a number of reasons I will discuss here.

This essay is an attempt to understand the Chinese financial system with a focus at the local government level and provide essential context for a better understanding of the current fiscal situation and how things are likely to unfold from here.

“Country Roads, Take Me Home”

Guizhou is located in China’s southwest region and surrounded by Yunnan, Guangxi, Sichuan/Chongqing and Hunan. Approximately the size of Missouri, its geography and terrain reminds me more of West Virginia: landlocked and mountainous, its namesake Gui Mountains reminiscent of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

While this topography makes for some stunning scenery, it also creates accessibility challenges and has historically been (and remains today) one of China’s most economically disadvantaged provinces. With per capita GDP of ¥52,321 ($7,774) in 2022, it ranks 28th out of 31 provinces and administrative divisions in China on this metric. Poverty is disproportionately concentrated in Guizhou’s minority populations which make up around two-fifths of the population.

As such, Guizhou has been at the center of China’s poverty alleviation policy which is based on two foundational pillars:

Broad-based economic transformation to open new economic opportunities

Targeted support to alleviate persistent poverty, particularly for areas disadvantaged by geography

Building roads and other infrastructure has been a crucial component of China’s economic development and poverty alleviation strategy. This was especially important in remote, mountainous regions of Guizhou. In the early 2000s, it would take more than 24 hours1 to travel from Guizhou to the more developed Pearl River Delta region through hundreds of miles of twisting, often treacherous roads or conventional rail track.

To fund these infrastructure projects, special-purpose entities known as local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) were set up to raise funds to finance construction.

Local Government Financing Vehicles

To understand LGFVs, one first needs to understand how land use is different in China vs. most other countries — especially the U.S. — and the central role that land has played (and continues to play) in China’s economic development over the past three decades:

In China, land is a scarce resource relative to its large population. This is the inverse of the United States, where land is plentiful relative to population. This fundamental reality has been a key driver in how land use policies and financing methods developed and is a key reason for vastly different approaches to land policy.

In China, local and provincial governments own and manage most of the land. Farmers, households and businesses may use the land by acquiring long-term land use rights. They only directly own the physical property and assets that sit on the land. This was formally codified into law in 20072.

LGFVs arose in part due to the conservative and relatively unsophisticated nature of the Chinese financial system. Fiscal reforms in the 90s decreased local governments’ share of tax revenues and prohibitions on direct borrowing by local governments were only lifted in 20153. Land is the easiest asset for China’s conservative banking system to finance and local governments control the land — thus, it was very natural for them to turn to LGFVs as the key vehicle for project finance.

While most recent commentary and analysis seems to have focused on the debt and liabilities side of the balance sheet, it is equally if not more important to understand the asset side of the balance sheet. LGFVs are asset-backed structures with revenue-generating or liquidatable assets to service and support the debt.

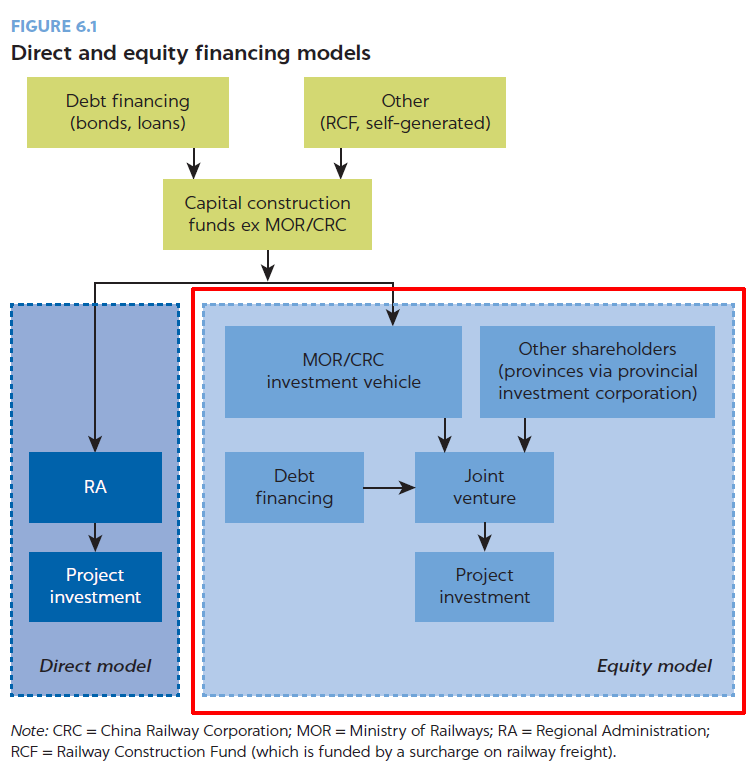

The financing of the build-out of the high-speed rail (HSR) network is instructive here. In a typical project, China Railway Corporation (CR) — the national SOE in charge of building and operating all of the country’s passenger rail network and most of its freight network — would set up a joint venture (JV) company with the provincial government.

Recent HSR development has been structured under the “equity financing model” (outlined in red below). The provincial government would contribute its equity in the form of land and the JV could raise project loans on the back of that land from banks. CR would raise funds (mainly through public bond offerings) and contribute the cash into the joint venture. Later, the JV might also raise its own bonds and re-finance the construction loans. This HSR JV structure is an example of one type of LGFV.

Besides infrastructure projects, there were other categories of LGFVs and not surprisingly, most were tied to land development in some way, like real estate construction itself.

Unlike infrastructure projects, which would typically have ongoing operating revenue to support debt service, real-estate LGFVs were used more as warehousing facilities where assets could be parked for a period of time until they were ready to be liquidated (e.g. when the apartment was purchased on the open market) with capital eventually released back to the provincial government and available to fund other activities. Wash, rinse, repeat.

Infrastructure and physical assets like real estate comprised 48% of LGFV assets in 2020 according to a longitudinal study by IMF in 2020.

Financial assets including accounts receivables, investments in securities, stakes in private companies, cash, loans, and other tangible assets made up about 48% of LGFV assets with the remaining 4% classified as intangible assets. Much of these financial assets represented working capital support to local governments to support their investment projects. Some of these financial assets include stakes in smaller SOEs that came out of the “Grasping of the Large, Letting go of the Small” (抓大放小) reforms in the 1990s.

For example, Kweichow Moutai was one of the smaller SOEs that was formally “let go”: its assets were restructured in 1999 under the ownership of the Guizhou Provincial People’s Government. It was listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange in 2001 and tracked the rise of the Chinese economy in the following two decades, its “firewater” recognized as the national drink not unlike Coca-Cola (53% alcohol content notwithstanding). Today, it is one of the world’s most valuable beverage companies and a market cap (~$311 billion) that has surpassed Coca-Cola’s. The Guizhou provincial government still owns more than half the shares.

One of the critical questions here is whether the assets are productive enough to offset their cost, which can be represented by their debt and liabilities. According to the IMF study of the financial statements of approximately 14,000 non-financial firms, the equity buffer was equivalent to 38% of total asset value. At face value, that is a relatively comfortable buffer but it is of course much more complicated than that.

With the exception of market-priced assets like Guizhou’s ownership stake in publicly traded Kweichou Moutai, most of these assets are valued at book value, which may or may not reflect the true value of the assets. The true value of the private assets needs to be assessed based on the fundamentals of the assets themselves. This could range from metrics like debt service coverage that provide signal on a LGFV’s ability generate enough revenue to cover its expenses (including interest) or asset-based metrics like working capital for assets that are meant to be liquidated like real estate developments.

And there are troubling signs. The IMF study found that around 77%4 of LGFV debt (¥38 trillion) was with entities that did not generate sufficient earnings to cover interest expenses for three consecutive years. LGFV assets reported as inventories comprise more than a quarter of aggregate balance sheets and increases in this number are indications that they are not being absorbed quickly enough by the market.

While troubling, these facts on their own do not necessarily indicate that on an aggregate basis, resources and capital were massively misallocated. Many of the assets are very long-term in nature and need time to mature — which could mean operating losses in the earlier years as the assets mature.

For example, the original World Bank project forecast from 2009 targeted 20 pairs of express passenger trains per day (~8 million passengers per year) on the GuiGuang HSR line. It achieved 25 train pairs by 2016 and today there are approximately ~60 train pairs5 running between Guangzhou and Guiyang indicated annual passenger traffic of more than 20 million6 — which is roughly the same amount as all of Amtrak. At these levels, the HSR line is covering all operating expenses, maintenance and interest with the ability to begin paying down some of the debt principal.

Even before factoring all of the non-financial benefits, it is clear that at least the ¥95 billion ($13.8 billion) invested in the GuiGuang HSR network and associated LGFV debt is worth at least the value recorded on the books and possibly much more.

Another feature of China’s conservative banking system is that it issues loans with tenors relatively short vs. the underlying long-lived assets that are being financed. For example, principal repayment on the original project loans on the GuiGuang HSR project began in 2017, only two years after it began operations. The World Bank (one of the project lenders), was not worried7:

GuiGuang line was not alone in this. Almost all the HSR lines, except Tokyo – Osaka, Paris – Lyon and a couple of lines in China have been financial viable, faced similar problems and CRC undertook a major debt restructuring, extending the tenors and restructuring principal repayments to gradually increasing over time to reflect the growth in traffic and revenue. With the restructuring, the long-term outlook for the company looks promising as the company will have adequate cash flows to cover interest charges, although in the short-term it will continue requiring support to absorb the infrastructure maintenance cost.

So when one reads about the “restructuring” of bank loans in China, it does not necessarily point to a solvency issue and is often more of a liquidity issue. The same is often true for LGFV bonds, which in Guizhou the WSJ article notes8 have an average tenor of just 3.4 years (down from 7 years a decade ago). This asset-debt timing mismatch is a function of the relative lack of sophistication and conservatism of China’s financial system.

Importance of infrastructure investment to poverty alleviation in Guizhou

The other complicating factor here is the reality that some provinces are wealthier and more prosperous than others. As introduced earlier, Guizhou is one of the least prosperous ones, due largely to its challenging topography that cuts off its access from the modern world: more than 92% of Guizhou’s land is covered in mountains and hills.

It is for that reason that Guizhou was ground zero for China’s national, top-down-driven poverty alleviation effort. The only way to fix this fundamental issue is to build infrastructure and that is why it featured so heavily in Guizhou’s plans.

In a recent People’s Daily article, the sheer numbers are eye-opening:

Credible sources indicated that by the end of 2022, Guizhou was home to nearly half of the world's 100 tallest bridges and four of the world's 10 tallest bridges. Fifteen bridges in Guizhou had won national and international awards by that time.

“We’ve built more than 28,000 highway bridges,” said Xu Xianghua, chief engineer of the Department of Transportation of Guizhou Province. The highway bridges that have been completed and are currently under construction add up to more than 5,400 km in Guizhou, Xu added.

By the end of 2022, the total highway mileage in Guizhou had exceeded 8,300 km, and that figure is expected to hit 9,500 km by the end of 2025.

Certain pundits have looked at this and in a very Rorschachian fashion concluded that the main takeaway from all this infrastructure investment is prima facie evidence of an economic growth model pushed to the extreme that has led to an unsustainable debt burden:

But even if this thesis were grounded in underlying asset performance (it’s not) which showed challenging financials, it’s still important to take into account non-financial poverty alleviation aspects of infrastructure building. One cannot focus solely on direct and short-term financial effects.

Stating the obvious but building bridges, tunnels and highways is the best way to connect difficult-to-access areas in mountainous regions like Guizhou. The People’s Daily article notes how the Zangke River bridge at Wumengshan National Geographical Park is expected to slash travel time from one hour to one minute, a 98% reduction. More broadly, rail travel from Guizhou to the Pearl River Delta has decreased by upwards of 85% since the GuiGuang HSR line opened.

Such massive reductions in travel times impact local residents in many ways that do not necessarily show up immediately (or at all) on LGFV income statements and local government coffers:

Increases quality of life — rising tide that lifts the value of existing local homes and businesses

Educational access — not having to trek two hours everyday to school means more people stick with it

Healthcare access — local residents can more easily access higher-quality healthcare services in larger towns and cities

Improved trade — opens up new trade routes for farmers and business people

Tourism — travelers from outside the region can more easily visit and help the local economy

And if done reasonably well, over the long run it will pay off.

Over the last two decades, Guizhou has grown faster relative to the rest of China. In 2002, Guizhou had per capita GDP (in 2022 real terms) of ¥7,020 ($848), which was 35% of China’s overall per capita GDP. In 2022, per capita GDP was ¥52,321 ($7,774), or 61% of China’s overall per capita GDP. This represents a real 9.2x increase at an 11.7% CAGR and Guizhou has significantly closed the gap with the rest of the country.

This is a seriously massive improvement in quality of life for the roughly 39 million residents of the province. The incremental quality of life improvements going from $848 (comparable to Sub-Saharan Burkina Faso today) to $7,774 (North Macedonia) are much greater than doubling it to ~$15,000 (Bulgaria).

By definition, social programs like poverty alleviation mean that investments may take longer to pay off or may never provide an adequate financial return on invested capital. Consequently, evaluating these projects solely on their short- to medium-term financials misses the bigger picture. There were both economic and social considerations justifying infrastructure investment in Guizhou.

This is not something that is unique to China: over the decades, billions have been spent on U.S. Route 48 (a.k.a. “Corridor H”) in West Virginia, a 153-mile stretch of highway that is part of the Appalachian Regional Development Act of 1965.

Projects that relied more on non-economic reasons still need to be paid for when the bills come due and the critical question today is who bears that cost.

How things unfold from here depends on two overarching questions

Is this a solvency or liquidity issue?

Who pays for the social costs?

First, let me make clear that I am not at all suggesting that there aren’t any problems here. The implicit guarantee provided by the state certainly created potential misalignment in incentives for local officials in charge of making major capital allocation decisions. There was a wide disparity in the competence and morality of local officials particularly in poor provinces like Guizhou that inevitably led to wide disparities in project quality and performance.

The reality is that nobody really quite knows exactly how wide this disparity was because there was so much investment and most of it was in illiquid assets that do not provide any market signals. Digging into the the financials of these companies is not easy and even if you can find the numbers, it does not mean the accounting values hold much meaning.

Guizhou is definitely sitting on a lot of debt. The Wall Street Journal estimated that including LGFV debt there is ¥2.67 trillion ($388 billion) in total debt, equivalent to 1.3x the province’s annual GDP.

With so many projects it is inevitable that there are also large numbers of poorly planned or executed projects throughout the province. These unfinished “vanity projects” in Dushan County are fairly obvious examples of impaired assets and debt.

In January, state-owned contractor Zunyi Road and Bridge Construction Group agreed with its creditor banks to restructure loans worth ¥15.6 billion ($2.3 billion), extending maturities and adjusting interest rates. The entity held total assets of ¥170 billion ($27 billion) against revenue of just ¥8.1 billion. Interest on ¥86 billion of interest-bearing debt alone could eat up the majority of the revenue.

But we also need to look at things from a system perspective. There were also projects that were clearly very good. The GuiGuang HSR project was completed on time and largely within budget9 and it has far exceeded its original ridership forecasts.

The difficult thing is figuring out how the good projects and bad projects net out. Unless we can do this type of analysis for most of the assets supporting all of the LGFV debt, it is very difficult to say for sure whether the book value of these assets reflects reality and whether the equity buffer (38% nationwide) is enough for the assets to cover the debts and liabilities.

In a similar vein, without doing this analysis, it is hard to take serious proclamations that there was so much malinvestment that the net asset values (including both good and bad projects) should be marked down >40% and not be able to cover its debt and liabilities.

This type of analysis is needed to determine whether the liquidity issues facing Guizhou and certain parts of the Chinese economy are indicative of underlying solvency (assets worth less than liabilities) or a function of an economy that is having a difficult time getting liquidity flowing after the pandemic and the government’s previous efforts of slamming the break on real estate to markets to keep a lid on speculative activity.

Complicating this is the fact that some of these projects were never designed to be fully solvent on their own. Infrastructure projects that had heavy poverty alleviation justifications still need to be paid for — e.g. highways connecting really remote and poor regions with no reasonable expectation of significant incremental increases in taxable economic activity (like Corridor H in West Virginia!).

This is a question that is beyond the scope of just Guizhou. These objectives were driven by national policy with Guizhou responsible for executing on the central government’s mandate to eliminate all extreme poverty by a certain date. If Guizhou performed well in meeting these objectives, naturally it should not be left hanging to dry when the bills come due.

There has long been an adversarial relationship between the central government and local/provincial governments. The central government sets high-level policies and the local/provincial governments are in charge of execution, as so much policy ultimately relates to land use. The central government is ultimately responsible for monitoring the performance of local governments and officials. Its disproportionate control of fiscal revenue streams is a powerful tool it uses to reward officials that execute well and identify those that do not.

It is a core feature, not a bug, of how China decentralizes decision-making and operational execution.

Guizhou is sitting on a lot of assets, including a single asset (its majority stake in Kweichow Moutai) that alone could theoretically cancel out nearly all of its collective LGFV debt.

Naturally, it wants to hold on to its assets and so this will come down to a negotiation with the central government, perhaps not dissimilar to a conversation between a parent and a teenager about his/her allowance. There is precedence for this as transfers from the central government already make up the bulk of Guizhou’s fiscal revenue.

At present we can assume that lots of people in the central administration and creditor banks are combing through LGFV financial statements in Guizhou and trying to determine the projects that were managed well and those that were not, and the officials responsible for managing them.

This analysis must be completed to determine how the losses are eventually covered and, more significantly, how to deal with impaired assets going forward. Ultimately part of the decision on how to allocate losses will be based on how best to deal with the specific impaired assets.

World Bank, “China - GuiGuang Railway Project” (July 2017)

“The project achieved a very significant reduction in the average travel time between the western region of southwest China and the Pearl River delta region. The average travel time came down dramatically from 1,500 minutes to 251 minutes.”

IMF “Local Government Financing Vehicles Revisited” (2020)

Corrected from the original version distributed on June 21st, 2023.

Based on an average 80% effective seat-yield.

World Bank, “China - GuiGuang Railway Project” (July 2017)

Wall Street Journal, “A Poor Province in China Splurged on Bridges and Roads. Now It’s Facing a Debt Reckoning” (May 2023)

“The average tenor of bonds issued by Guizhou’s LGFVs is currently around 3.4 years; a decade ago it was seven years, according to Wind.”

The 856-km GuiGuang HSR project cost ¥94.6 billion ($13.8 billion) in total construction cost. It came in higher than its budget, but the World Bank noted that this was entirely due to increasing the technical specification of the track to accommodate higher speeds than originally designed. At $16 million per km, the GuiGuang project was also slightly below the average per-km cost ($17-21 million per km) from that time, despite the more challenging mountainous terrain.

Great read if only for the great Guizhou photos! Great point about there being a non-financial return to these projects, the benefit of the doubt California's over budget HSR project gets doesn't get applied elsewhere

Incredible post thank you glenn