Paradox of China's stock market and economic growth

Beijing's seeming indifference to stock market valuations vs. its overwhelming focus on economic growth

Joe Weisenthal of Bloomberg and the Odd Lots posed this question on Twitter/X:

“Given that the stock market hasn’t been especially rewarding to the volume-over-profits strategy undertaken by big Chinese manufacturers, what policy levers does Beijing have to sustain and encourage the existing approach?”

Many people may have noticed that despite the impressive growth of Chinese manufacturers in sectors like electric vehicles, the market capitalizations of these companies are dwarfed by Tesla. This seeming paradox lies at the heart of the the question posed by Joe.

In 2020, I shared an observation that China cares much more about GDP than market capitalization. I was making this observation in the context of Alibaba1 but would soon broaden the observation to encapsulate many more situations. In sharp contrast to Americans, Beijing just does not seem to care that much about equity market valuations but do seem to very much care about domestic growth and economic development.

This is quite an enigma because many (if not most) of us grew up equating the stock market with the health of the underlying economy. Indeed, renowned capitalist Warren Buffett, who is by some barometers more celebrated in China than America, is known for the “Buffett Indicator” that explicitly ties stock market capitalization to GDP. In his annual letters, he has repeatedly talked about his confidence in the stock market on the basis of the last two centuries of continuous economic development and growth in America.

Those who know me know I am a huge fan of Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway. One area where I have evolved my opinion with respect to China over the last decade is that key elements of his “value investing” style just would not work, particularly as Berkshire Hathaway has accumulated an ever-increasing capital base2.

I have been pondering various iterations of this question for much of the last decade. While it might seem like a simple question, a proper answer is necessarily complex and requires a multi-faceted approach involving not just economics but other disciplines including accounting and philosophy.

The particular approach I will take here today to analyze this question is to break this down into more finite, digestible components and consider how Chinese policy impacts each of these components.

“Stock market” a.k.a. Market cap = Profits (to equity) x Market multiple

Profits = Volume x Profits per unit

Profits per unit is a function of revenue and operating expenses, in particular fixed overhead and variable costs

Profits to equity = Profits less return on debt (interest expenses) and taxes

Market multiple = A function of many factors, including at times (it seems) magic

The positive effects of volume on profit

In the traditional manufacturing model, profits are a function of the residual after fixed overhead (including capex via depreciation, factory overhead and R&D) and variable costs. Fixed overhead unit cost are ultimately a function of volume: the more volume, the larger unit base on which a company can amortize fixed costs.

For fixed overhead, volume is your friend.

Meanwhile, variable costs will be line items like energy and materials inputs, third-party component costs and retail/distribution3. In the past, with labor-intensive manufacturing, labor was a variable input but for advanced manufacturing it has shrunk.

All things equal, scale can drive profit growth. If a company has fixed overhead of $1,000 and sells 10 widgets, its fixed overhead per widget is $100. If it sells 100 widgets, fixed overhead per widget declines tenfold and all things equal, profit per widget rises commensurately.

“Scale matters” in manufacturing and the natural instinct for Chinese manufacturing companies is the rapid pursuit of scale to establish a defensible market position.

One company’s variable cost is another’s fixed overhead

In a complex manufacturing supply chain, costs that are variable to the purchasing department of a manufacturer represent the revenue of an upstream supplier. For example, BYD runs a ~20% gross margin which factors in both fixed overhead and variable costs. It purchases large amounts of aluminum from upstream aluminum suppliers (e.g. Chalco) that would be counted as variable costs on its income statement.

If we now turn our attention to Chalco’s income statement, we will find that it also has its own fixed and variable overhead structure, which we can break down similarly to how we have done above. We can continue to recursively make our way farther and farther upstream in the supply chain involving Tertiary (mainly services) to Secondary (mainly manufacturing) to Primary (mainly extractive) sectors.

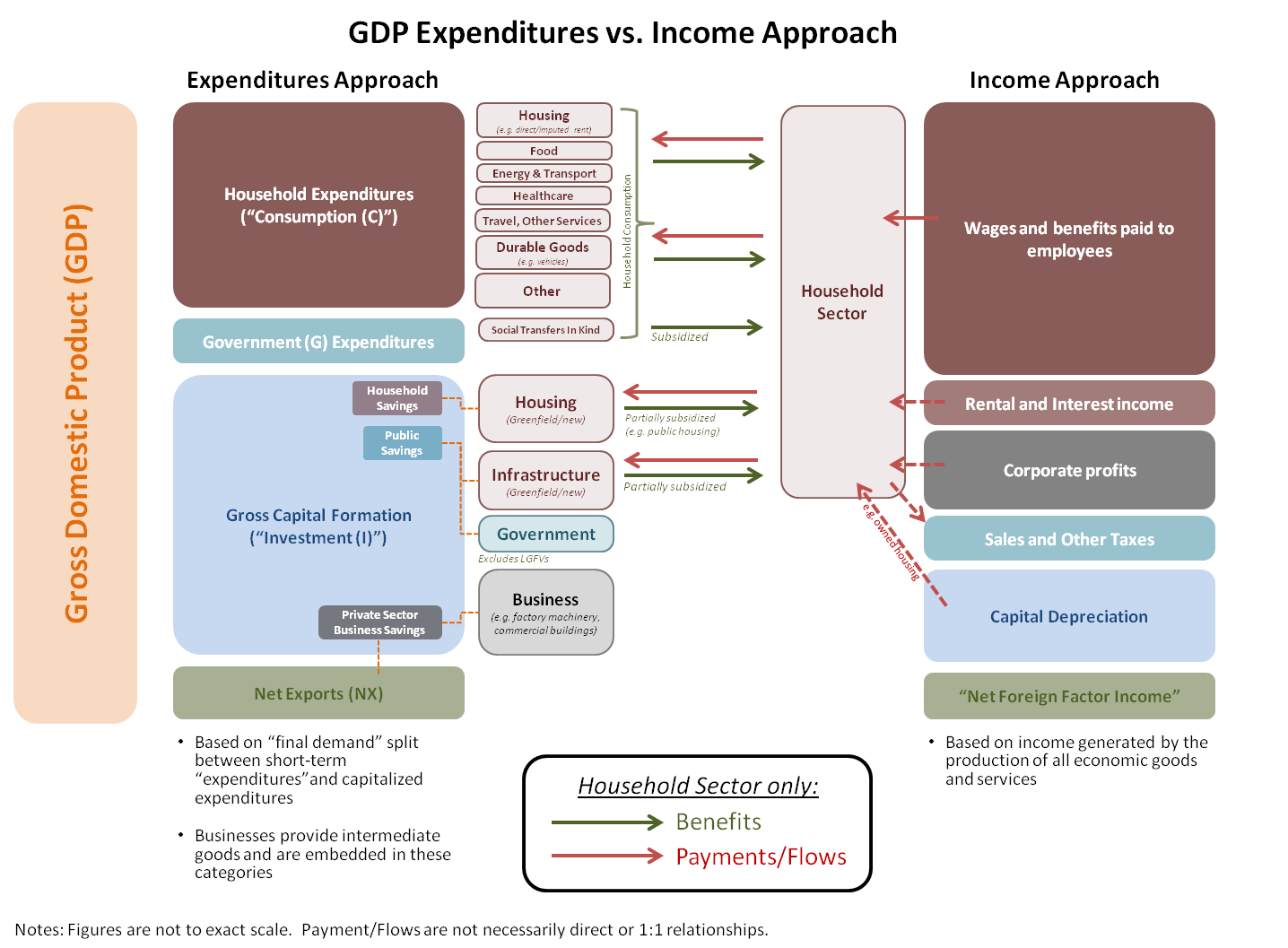

Ultimately, we will discover that the majority of “operating costs” in society are simply labor costs. There is a question of how labor cost is categorized: either as expenditures (consumed within a year) or counted as gross capital formation and consumed over time. On top of this we also have separate categories for corporate income and government expenditures. In effect, this is a reconstruction the income approach to calculated gross domestic production (GDP), shown here on the right-hand side:

The trade-off between current profit and future growth

When a manufacturer generates incremental profit — through any combination of various approachs volume growth, production efficiencies, more leverage over suppliers, etc. — an important decision is whether to return these profits to capital holders (dividends or stock buybacks) or reinvest back into the business (retained earnings) presumably with the rational expectation of some kind of incremental return on investment.

Increasingly as manufacturing has become more automated in China, this means more reinvestment takes the form of line items like R&D and marketing (brand-building) instead of traditional capitalized expenditures like factory equipment. The accounting affect is delayed gratification: current-period operating profits are sacrificed for growth in future profits.

Once again turning to BYD as an example, in 2023 it increased its number of research personnel by over 50%. This increased R&D investment represents a massive reinvestment of earnings back into future growth — improved car models, less expensive batteries, expansion in manufacturing capacity.

The ideas captured in the “overcapacity is a feature, not a bug” phrase are also relevant here. Rapid expansion in manufacturing capacity requiring large amounts of expenditures can depress financial profits, even if most of those expenditures are capitalized as factory assets. Depreciation of this factory equipment is often mismatched with the actual underlying usage of the equipment over its entire useful life. This can result in depressed earnings, especially as factories are still in ramp-up mode.

While all of this should be theoretically reflected in the market multiple (in the form of higher growth expectations on profits to equity owners), as I will discuss later on, this is not the only factor that determines valuations in the public markets.

Labor vs. capital

In society, a balance must be struck in how economic gains are split between labor and capital (i.e. profits on capital investment). On the one hand, it is zero-sum because $1 of economic gain can only be split it between labor and return on capital. It is non-zero-sum in how this split might ultimately impact long-term growth of those economic gains.

Compared to Western capitalist nations, in China the general policy orientation is to favor labor over capital, especially privately owned equity capital (vs. state-owned equity such as state-owned enterprises). You can see this in how so many policies favor labor, especially lower-income labor, for example:

Foreign exchange policies that encourage weak currency, which makes Chinese labor cheaper compared to foreign labor on a productivity-adjusted basis

Policies to encourage a relatively labor-intensive manufacturing model as the basis of industrialization

Heavy stimulus programs during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in reaction to the sudden loss of millions of jobs in the export processing sector

Prioritization of labor encompasses more than just rising wages and incomes for the gainfully employed, but spillover knowledge benefits that contribute to building up the hard-to-measure but significant human capital asset on the national balance sheet.

The question of balance is important. Do you favor labor over capital so much that private entrepreneurs become less motivated? This is a huge, extremely complex and nuanced question that one can argue is more philosophical than economics.

But we can look at this empirically by watching the behavior of private entrepreneurs as well: China has notably cracked down on some areas of the private sector (like Internet and Fintech) while encouraging others (like advanced manufacturing). Its policies have had a notable impact on growth (or lack thereof) in these respective areas.

Debt vs. equity financing

One of major differences between China and the United States is how long-term investments in the economy are financed. In China, the dominant financing approach for capital-intensive industries is debt, mainly funneled through the state-controlled banking system:

Out of Total Social Financing representing ~294% of GDP in 2023, only 3% was accounted for by equity financing. Even though this figure does not include all forms of equity4 it still shows how much more important debt is than equity financing in China.

The dominant household asset class in China is equity held in real estate instead of the stock market or other liquid assets.

The stock market is an equity concept. The implication here with the primacy of debt over equity is that the performance of the domestic stock market is much less indicative of the underlying health of the overall economy5. For these reasons, the “Buffett Indicator” is largely irrelevant for China.

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) also tend to play a disproportionate role in industry sectors that are by nature capital-intensive. As a result, they are also by far the largest users of debt. Tight state control over the state banking system (household and private sector business deposits) allow the banking sector to provide financing at a relatively low cost, especially compared to developing nations. For capital-intensive industries, this is an advantage.

Chinese manufacturing companies tend to be more private sector oriented and less capital-intensive business models compared to industries SOEs tend to operate in. For example, BYD’s is mainly capitalized with equity and does not feature significant long-term borrowings despite investing increasingly large amounts into expanding manufacturing capacity.

Mr. Market and market multiples

To borrow from another Warren Buffett favorite, “Mr. Market” was an allegory created by his mentor Benjamin Graham to characterize a stock market that at times seemed irrational and temperamental. One key lesson of this allegory was to recognize groupthink in the markets and “to be greedy when others are fearful and to be fearful when others are greedy”.

Much of Mr. Market’s temperament can be captured in a variety of market multiples that investment banking analysts develop a lifelong passion for calculating in increasingly arcane formulations:

Price to earnings

Price-to-book value

EV-to-unleveraged-FCF, EV/EBITDA, EV/Revenue

And my favorite: Wework’s “community adjusted” EV/EBITDA where adjustments include adding back opex (both real and imagined) 6

All things equal, high multiples mean that Mr. Market is happy and exuberant while low multiples indicate a sadder, more despondent version.

Of course, temperament is not the only factor. Interest rates (opportunity cost of capital), risk perception, economic growth (and how it translates into growth in profits to shareholders), tax policy (how operating profits are shared between the government and business) etc. can all play a role in driving market multiples.

Except for perhaps a brief period before the GFC (when PetroChina A-shares drove an implied market capitalization of over a $1 trillion), Chinese market multiples have tended to be much lower than U.S. equity market multiples. And this gap has only been increasing over the last decade.

Even a company like BYD which has been growing faster than Tesla tends to have a lower market multiple. Or compare a company like Alibaba that is trading at veritable early Buffett “cigar butt” levels to Amazon.

While the “Buffett Indicator” might help with market timing and provide some measure of how “cheap” or “expensive” the market may be, Warren Buffett himself pays attention more to underlying earnings and even Berkshire Hathaway’s book-value per share (BVPS) than the more volatile market capitalization of Berkshire Hathaway which is subject to the changing emotions of Mr. Market.

For the first four-plus decades of of his annual letters7 to shareholders of the former textile mill, he exhorted investors to pay attention to Berkshire Hathaway’s BVPS in favor of its stock price — not because BVPS was a more accurate formulation of the more abstract and difficult-to-precisely-measure “intrinsic value” concept, but because it was a better indication of how intrinsic value was trending.

This actually illustrates an important and related concept — that the “mood swings” of Mr. Market should not have a meaningful effect on the underlying operations of the business, better captured by measures like annual operating earnings (but even then subject to the limitations of accounting described above). In short, stock market valuation at a given point in time could very well be driven by factors completely divorced from the underlying performance of an economy, especially one that (per above) relies much more on debt financing anyway.

The “Dungeon Master”

With respect to private sector market forces, Beijing tends to see its role as coordinators of an elaborate “game” that is meant to foster industry dynamics that drive desired market behaviors. The metaphor I sometimes use is as the Dungeon Master role in Dungeons & Dragons8.

These “desired market behaviors” tend to overwhelmingly revolve around this focused effort to maximize economic development and growth over multiple decades. Beijing has been very consistent about the goal to become “fully developed” by the middle of the 21st century9.

To date, I would say that Chinese policymakers have been relatively successful using the approaches and principles described above to drive economic growth:

Priority on labor over capital / wage growth over capital income growth. Prioritizing labor is a key pillar of China’s demand-side support strategy. Growth in household income drives growth in domestic demand (whether in the form of household gross capital formation or expenditures).

Setting up rules to foster the create competitive industry dynamics and motivate economic actors to reinvest earnings back into growth.

Periodic crackdowns to disrupt what is perceived to be rent-seeking behavior, particularly from private sector players that have accumulated large amounts of equity capital (vs. small family businesses):

Anti-competitive behavior (e.g. Alibaba e-commerce dominance in the late 2010s)

Regulatory arbitrage (moral hazards inherent in Ant Financial’s risk-sharing arrangement with SOE banks)

Societal effects (for-profit education driving “standing on tiptoes” approach to childhood education)

Supply-side support to encourage dynamic, entrepreneurial participation from private sector players like in the clean energy transition to drive rapid industry through scale and scale-related production efficiencies. China has relied on supply-side strategies to support economic for decades despite repeated exhortations by outsiders to implement OECD-style income transfers.

Encouraging industry consolidation (vs. long drawn-out bankruptcies) once sectors have reached maturity although there are often conflicting motivations between Beijing and local governments.

A consistent theme is Beijing’s paranoia to rent-seeking behavior by capitalists (especially those who have accumulated large amounts of capital). It is sensitive to the potential stakeholder misalignment when capitalists — who are primarily aligned with one stakeholder class (fiduciary duty to equity owners).

It would prefer that rent-seeking behavior be handled by the party instead, whose objective (at least in theory) is to distribute these rents back to “The People” — although naturally in practice it never turns out this way; Yuen Yuen Ang has written multiple volumes about the prevalence of Chinese-style corruption and its corrosive economic effects.

So to bring it back to Joe’s question, the answer on whether Chinese policymakers can continue these policies going forward very much revolves around public goods and rent-seeking: is it better to be handled by the government or by private sector capitalists? What should be abundantly clear is that Beijing is definitive on this question: the party will maintain a tight grip, if not outright monopoly, on rent-seeking.

Will this dampen the “animal spirits” of entrepreneurs and private capital that play such a critical role in focus industries like the clean energy? So far it does not seem to have slowed them down much at all — quite the opposite in fact. This is despite financial returns on capital not being particularly high, often quite volatile / difficult to predict, and Mr. Market often assigning market multiples that are at times indicative of extreme levels of depression.

This remains a puzzle and paradox and something that we can only observe over long periods of time to truly judge whether this was ultimately the right approach for the “Dungeon Masters” in Beijing to take.

How despite the rising geopolitical enmity between the United States and Japan and China, China seemed to not really mind that American (e.g. Yahoo) and Japanese (e.g. Softbank) shareholders were the big winners in Alibaba. What they seemed to care much more about was the impact Alibaba’s e-commerce businesses had on the development of the domestic economy. We would soon find out with the crackdown on fintech, particularly the impact on Alibaba’s affiliate Ant Financial, just how much more it cared about “GDP” than market capitalization.

Many of Berkshire’s larger acquisitions have regulatory-based economic moats, which is a euphemism for rent-seeking. This just would not work in China, even for insider capitalists.

The irony, of course is that despite this, Berkshire Hathaway has nonetheless selected two of the biggest absolute-dollar winners in Chinese stockpicking history (PetroChina and BYD). Warren Buffett and especially the late Charlie Munger seemed to recognize this and took it into account in their approach to China.

In auto manufacturing, this would include a significant portion of the costs of a dealer network e.g. sales commissions paid to salespeople.

This figure is derived from formal equity financings (IPOs) on domestic bourses and represents a book (not market) figure. This does not represent FDI or informal equity in small businesses.

There are other reasons here as well besides the small proportion of equity in financing. There is also selection bias in the types of companies that list on domestic bourses that makes it less representative of the overall economy.

From his 1972 letter where he talks about the “increase in book value from $19.46 per share at fiscal year-end 1964 to $69.72 at 1972 year-end” to his 2013 letter. Starting with the 2014 letter, he discloses Berkshire Hathaway’s market value per share. This was in response to the evolution of Berkshire from an early insurance operation with a large public investment portfolio where mark-to-market gains on its listed securities would be captures in BVPS. As it transformed into a diversified conglomerate, its intrinsic value was increasingly driven by the operating earnings of these private businesses which book value would not capture accurately. Hence the addition of the market-value-per-share column (notably he still kept the BVPS column).

I did not play Dungeons & Dragons growing up but I did play role-playing games like the Ultima as well as MUDs on the early Internet (text-based precursors to modern real-time RPGs like World of Warcraft and League of Legends).

I intrepret this goal at a high-level to achieve between 50-75% of U.S. per capita GDP by 2050 using purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusted GDP from ~30% today.

There is also some expectation that nominal USD-CNY rates will converge in the very long-term closer to PPP-adjusted rates. My theory is based on shifting economic policy priorities from maximizing “full gainful employment” to a gradual shift away from this policy once China reaches full urbanization.

Like presumably every other greedy pig who wouldn't mind making some easy money out of what is clearly a runaway economic miracle, I have asked myself this very same question.

Problem is the Dungeon Master runs an exclusive club comprising circa top 10% of adults in terms of influence (and perhaps talent), his relatively well-run ship is cash rich, and if his priority is generally "for the people", what exactly could random rentiers local or foreign bring to the party?

You mention Yuen Yuen Ang's 2nd book, her 1st book highlights the importance of customising solutions to problems - yet we were taught Adam Smith's invisible hand is not only helpful, but essential with the USSR as exhibit A. Inconveniently, the Dungeon Master's visible hand is delivering superior results, so much so that driven by fear of obsolescence leaders in the land of B-schools are cussing loudly and changing tack. Now the question is whether erecting high fence sprinkling helicopter money in yard small or otherwise (but without the club, its adaptiveness, or priority) can hold a candle. I am willing to bet a Big Mac it is too little, too late.

An under-reported policy favoring labor is Beijing's consistent allocation of 58% of GDP to wages.