LGFVs: the Good, the Bad, and the Mierda, Part II

How local government assets fit within the broader Chinese economy

This is the next installment of a series of deep dives into local government assets and financing vehicles (LGFVs) in China:

In the previous post, we examined various categories of assets that make up the bulk of the LGFV portfolio. In this essay, we will step out and see where these assets fit and intersect with others in the broader Chinese economy, namely assets held by the central government and the private sector.

The Holy Trinity of Assets

One way to look at the Chinese economy from an asset perspective is to divide it into three distinct pillars:

Private Sector

Central Government

Local Government

Each grouping has its advantages and disadvantages within the context of the Chinese system and over time that has led to each finding its way to certain preferred sectors and types of economic activity.

Private Sector Assets

The private sector emerged over the past four decades out of China’s once-100% planned economy. Much of the development of the private sector has been driven by entrepreneurs trying to find spaces within the Chinese economy where they could pursue either “Blue Ocean” strategies or co-exist or compete successfully with the state.

Today, the private sector has taken the lead in sectors like agriculture, manufacturing, travel and tourism, technology, Internet and real estate. Examples of successful private sector companies include Alibaba, Foxconn, Huawei and BYD.

Private sector companies are generally less capital-intensive than SOEs. Part of this is simply a function of capital being more expensive, typically relying on higher-cost equity to capitalize their businesses instead of relatively inexpensive bank loans. This served as a forcing function for them to operate more efficiently. Another part of this was being explictly crowded out of capital-intensive domestic sectors by the state itself (more on this below).

Market competition weeds out poor performers, rewarding better operators with higher profits that can be re-invested back into the business via retained earnings. Despite its cost of capital disadvantages, higher efficiency and growth rates have led to impressive accumulation in its asset base: private sector industrial companies held aggregate assets of approximately $6 trillion as of the end of 20221.

Off this asset base, the private sector is generally able to generate significantly higher returns on capital compared to SOEs:

The private sector is the most dynamic segment of the Chinese economy, and for the most part succeeded in dutifully followed Deng’s exhortation “to get rich is glorious” in the 1980s. There is the famous “60/70/80/90” observation2 that the private sector contributes:

>60% of GDP

>70% of technological innovations

>80% of urban employment

>90% of new job creation

Central Government Assets

National SOEs are primarily held under the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) of the State Council. Established in 2003, currently SASAC oversees 98 centrally owned corporations3 that represent combined assets and revenue of $30 trillion and include listed companies or subsidiaries with combined market capitalization of $10 trillion4. National SOEs play critical roles in executing China’s national policy objectives and industrial policy.

SASAC’s closest comparable might be Singapore’s Temasek, which was established in 1974 and manages approximately $500 billion of assets under management including a number of GLCs (Government-Linked Corporations) such as Singapore Airlines, Singtel (telecom network) and SMRT Corporation (public transport). Temasek also manages a more liquid portfolio worth approximately $300 billion as of 2022.

Local Government Assets

These include all the assets held at the provincial level and below discussed in last week’s post, such as infrastructure assets, real estate, various investments in local businesses, etc. As discussed, local governments took a lead role in two of China’s most significant multi-decade development efforts: urbanization and infrastructure.

When evaluated solely based on financial returns, both private sector assets and national SOEs outperform assets held and managed by local governments. Assets held in LGFVs skew towards the “bottom of the barrel” of the Chinese economy — they generally represent the lowest-quality assets, financially speaking, within the collective asset pool5.

Adverse selection bias plays a significant role for these low financial returns:

Local governments are generally restricted to certain asset categories in their geographic regions, often related to land. Unleveraged financial rates of return tend to be lower for real estate compared to business investment. The flipside is that the useful life of real estate assets tends to be much longer6 — lower percentage rates of return but over a longer time horizon.

Local governments played a disproportionate role in nationally directed social programs such as poverty alleviation and projects were underwritten with a higher proportion of non-financial considerations.

Competency levels are generally lower with greater variation — and scope for corruption higher — at the local level compared to the central government.

Judging by most traditional financial metrics, it is quite clear that a significant share of LGFV assets are financially impaired. This IMF study found that around 77% of LGFV debt (¥38 trillion in 2020) was with entities that did not generate sufficient earnings to cover interest expenses for three consecutive years.

This chart below shows how LGFVs in aggregate generate significantly less operating inflows that can offset operating outflows7.

It is not easy to determine the extent to which various factors — asset type, degree of non-financial social considerations, incompetence, corruption, luck — contributed to these outcomes without conducting comprehensive project-level assessments.

The scope of that work goes a level or three deeper than this essay8. However, what I can offer here is a high-level analytical framework to understand how these assessments might be conducted.

The State vs. the Private Sector

One way to illustrate the national vs. local vs. private sector dynamic is by analyzing a specific industry, such as the rail sector. In the table below, we can visualize the intersections and role distinctions between regulators, national operators, local governments, and the private sector.

There are a few generalized distinctions9 that stand out to help describe the various roles played by the state and private sector and the industries to which they gravitate:

Capital intensity

Social responsibilities

Management of public assets / rent-seeking sectors

(i) Capital intensity

The state typically engages in sectors that feature high levels of capital intensity. Access to relatively inexpensive debt financing from the formal banking sector plays a large role in this dynamic. Within the state sector, national SOEs tend to operate in “commanding heights”, domestically focused industries while local governments hold jurisdiction on land development.

Private sector assets tend to be more capital-light. Most export-oriented businesses are relatively asset-light and owned and operated by private capital. Most “new” industries that require agility and innovation are private businesses. The vast majority of small businesses, services businesses and farms are owned by private sector entrepreneurs or individuals.

(ii) Social responsibilities

There is a social role that touches all of these groupings. Private sector companies tend to carry the least amount of social responsibilities; they mainly have to comply with varying degrees of regulation (depending on sector) designed to look out for the interests of stakeholders beyond the capital holders.

Depending on the industry, there may be both positive and negative societal externalities. For example, one of the more fundamental societal spillovers is job creation that can upgrade worker skills and raise the level of human capital. An example of a negative spillover might be potential environmental damage caused by enterprises in heavy industry.

National SOEs assume a more direct role fulfilling certain social policy objectives. In the HSR example, passenger tariffs are not set to maximize financial profitability or returns on equity10. China Railway sets passenger and freight tariffs to achieve roughly breakeven after paying interest to debt holders. In other words, it targets a zero return on equity.

Over time, this policy has resulted in ticket prices increasing much slower than both inflation and disposable income11. In some cases, ticket prices have even declined in nominal terms since the routes first became operational more than a decade ago:

Holding passenger tariffs steady in nominal terms over an extended period of time generates significant consumer surplus. This is how HSR has become affordable to the masses, despite worries early on that it would only be used by affluent travelers. Instead of generating direct financial returns on its equity, China Railway counts this massive consumer surplus as its indirect return on equity — which in the long run can translate into both faster economic development and higher standards of living.

With its jurisdiction over the land, local governments assume direct responsibility for achieving social objectives at the national level. Most of the key social burdens like education, healthcare access and poverty alleviation fall within this local scope. These responsibilities inevitably result in lower financial returns and higher levels of “non-market” asset creation.

(iii) Management of public assets / rent-seeking sectors

Economic rent-seeking is when economic actors seek to leverage their relationships, typically with the government, to increase their share of wealth without necessarily creating societal value. It is enlarging one’s share of the pie without increasing the size of the pie or even shrinking the pie — “zero sum” or worse economic activity.

Rent-seeking behavior tends to concentrate in domestic industries that involve public goods and assets. These include natural monopolies such as electricity transmission and telecom networks and extractive industries like petroleum and mining. In China, rent-seeking industries are dominated by SOEs. For better or worse, Chinese policymakers believe that the incentives of state-owned entities are better aligned with society, which is more important for traditional rent-seeking industries where decisions are made on how public assets are used12.

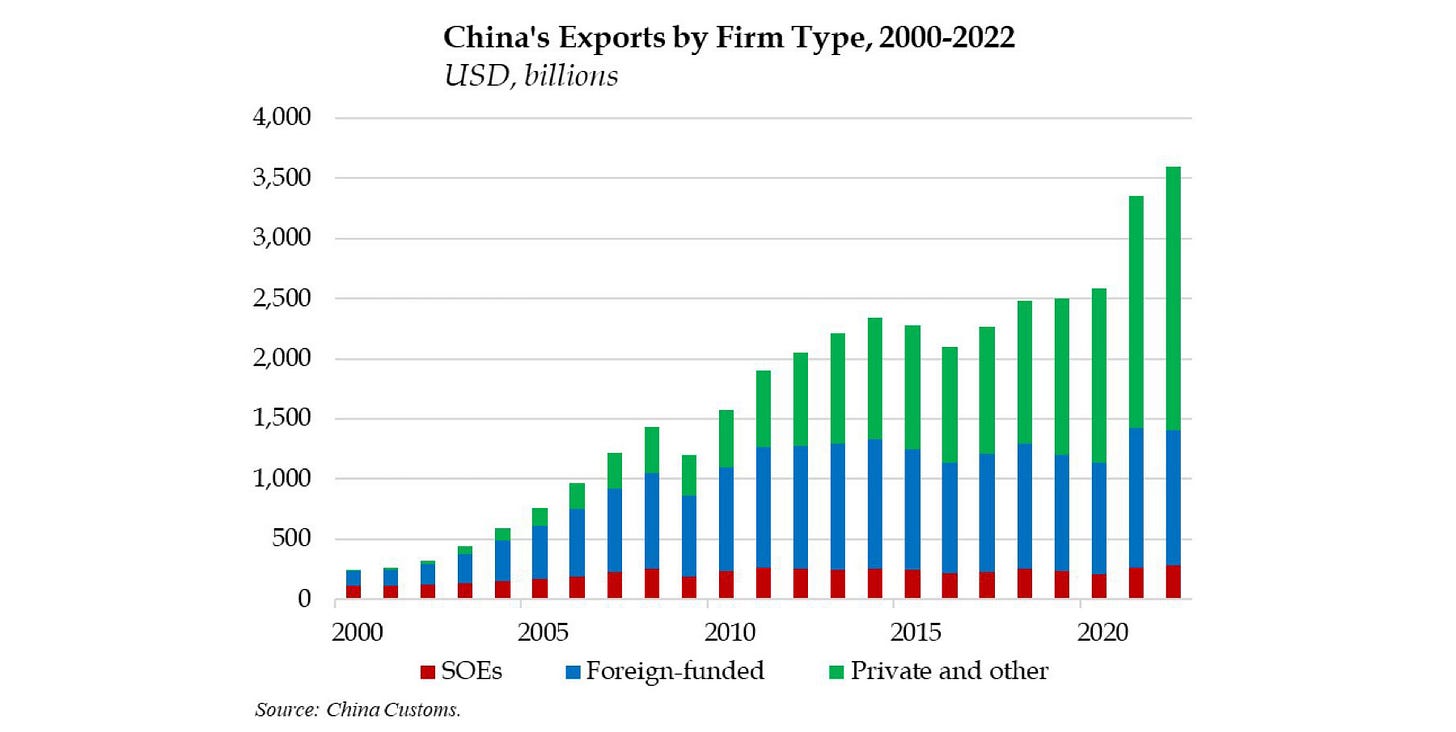

Whether push or pull, the private sector tends to cluster in non-rent-seeking industries. The prime example here are export-oriented industries where manufacturers must compete in brutally competitive global markets. Indeed, far from relying on domestic political patronage, successful exporters must overcome major hurdles (often themselves political in nature) to be able to be successfully compete in foreign markets.

As you can see in the table below, China’s exports are dominated by private sector (both foreign and domestically funded):

Economic Return on Investment

Currently, one of the critical questions is figuring out how to deal with the growing pile of assets held at the local level in LGFVs. In its oversight role, Chinese central government policymakers cannot only evaluate the performance of local governments on the basis of the financial returns of the assets created under their watch.

What if its explicit mandate has been to oversee the development of assets that from the outset were never expected to support themselves financially? Was it skill or luck? What if a project performed well despite corruption?

The end goal here for Chinese policymakers is to figure out how to reform the local government system and governance, better manage assets that have been created, and improve capital deployment going forward. Part of achieving these goals is figuring out which local governments performed their duties well, and which did not. They cannot be judged purely based on short and medium-term financial returns.

Enter “Economic Rate of Return” or “Economic RoI” — this is a term that the World Bank used in its analysis of China’s national HSR build-out in 2019 and seeks to encompass both Financial RoI and non-financial “Social RoI”:

Overall, the economic results appear positive, even at this early stage. The economic rate of return of the network as it was in 2015 is estimated at 8 percent, well above the opportunity cost of capital adopted in China and most other countries for such major long-term infrastructure investments. There is thus a reason to be optimistic about the long-term economic viability of the major trunk railways of the HSR program in China

In the case of HSR, the World Bank looked at value embedded in categories such as user time savings, job creation, and agglomeration benefits and offset against direct costs (construction and ongoing operations) and indirect ones like greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Some of these costs could be captured in the financials while others could not.

The efficient frontier of economic development

We can take this framework and generalize it for other industries and asset classes, mapping out Financial RoI on the y-axis and Social RoI on the x-axis. Similar to the concept of an efficient frontier from Efficient Market Hypothesis from introductory finance13, you can also draw one out to account for non-financial social impacts, replacing the risk axis.

I would emphasize that the above table is merely illustrative and not based on robust project-level evaluations. But using this illustrative example, we can identify asset classes that are either far from or well beyond the “Efficient Frontier”. This helps indicate which assets deserve more or less capital, resources, and attention.

It is important to recognize that evaluating social returns is always going to be more subjective. One advantage of financial returns is their precision. They are built on actual revenues collected, costs expended, and underpinned by a stream of arms-length transactions by independent actors. In contrast, social returns are often based on models, subjective and dependent on inputs and assumptions.

However, just because things are hard to measure precisely does not mean they do not matter. Social returns capture impacts beyond those directly captured in the financial statements only affecting capital holders (e.g. debt and equity). It broadens to scope to reflect impacts on other stakeholders including:

Employees (job creation, skills accumulation)

Customers (consumer surplus)

Local communities (agglomeration effects)

Chinese society-at-large (long-term economic development)

The global community (GHG admissions)

Taking the framework another level deeper

When I worked in venture capital and private equity, we would often undertake a “fresh look” assessment on investments after a certain period of time had elapsed. We would dig out the original investment and underwriting memos and try to see which parts of the investment thesis and forecast we had gotten right, and which parts we had gotten wrong and determine what corrective actions, if any, should be taken.

A similar “fresh look” assessment can be undertaken here by taking this framework another level deeper. For example, once again using HSR as a case study, we can do the same type of analysis on a project-by-project basis to see which projects performed better than others.

As you can imagine, with trillions of dollars worth of projects at the local level, this is a tremendous amount of work. I presume some variation of this “fresh look” analysis is going on right now in oversight bodies such as the NDRC and National Audit Office. Many man-hours are going into reviewing these local projects. I expect that we will see results of this work percolate in the next batch of reforms.

In what I expect to be the next and last installment of this series on local government assets, I will talk about the path forward and provide thoughts on potential reforms based on these asset-based frameworks and analyses.

National Bureau of Statistics (Industry / Main Indicators of Industry / Total Assets)

There are different variations on this theme, including the private sector accounting for 50% of tax revenue, 70% of investment, 90% of exports and 90% of market entities.

Market cap does not include non-listed entities, which are substantial.

The assets in the graphic below do not represent all the assets in the Chinese economy. Notably, household real estate assets (an estimated $33 trillion market value as of 2019) are excluded. Another excluded balance sheet asset are net foreign assets of approximately $6 trillion.

This can be seen in estimates of depreciation percentages used for real estate vs. business investments. Source: World Bank “China’s Productivity Slowdown and Future Growth Potential” (June 2020)

Note, a large part of “Operations” outflows includes build-up of inventory, which is real estate under construction that is meant to be liquidated. The operating model for these types of LGFV assets is a bit different from an operating business like a highway or airport and fits within The Structured Asset-Backed Warehousing LGFV asset type I described in last week’s post.

I suspect that this work is ongoing in real-time by Chinese policymaking bodies and discuss more in the next installment of this series.

These are merely high-level distinctions and not the only ones. State vs. private sector is not always black and white but shades of gray e.g. privately owned companies such as Huawei that serve highly regulated and strategic industries like the telecom network.

In this case the “equityholder” is the central government, who owns 100% of China Railway through the Ministry of Finance.

Since 2010, disposable income in China has grown by 3.2x (9.5% CAGR) in nominal terms and increased as a share of GDP from 41% to 43%. In real terms, it has grown approximately 2.2x at a 6.3% CAGR.

No doubt Chinese policymakers have looked to positive examples in other economies like Japan, South Korea and Singapore to formulate their own approaches. They have also studied negative examples like the Soviet Union and Russia where chaotic, large-scale privatization resulted in a major transfer of public wealth from the state to private shareholders in rent-seeking and extractive industries, leading to the rise of a highly concentrated group of oligarchs that control the economy to this day.

At least for me in the late 1990s — from Brealey & Myers

Really insightful analysis of the LGFVs, I learned a thing or two.

As for a good measurement of the social returns, I'd propose something a bit more old-school identified by Marx already in Grundrisse: free time. That is, free time for the full and universal development of the individual. This is something the CPC can easily adopt. Even infrastructural investments such as the HSR or improved communications (5G, Alipay) can be seen from that light: e.g an hour-long trip reduced to 2 minutes via a Guizhou bridge or robotics displacing blue-collar work up until the average Chinese worker can have a more relaxed, lengthy and fruitful life. This WILL come intro contradiction with China's emphasis on accumulation rather than freeing up time for society. It's a feature of capital after all that all the improvements in its productivity go towards its further accumulation, rather than freeing up the labourer's time.

Leaving this insightful Marx quote too:

"The saving of labour time [is] equal to an increase of free time, i.e. time for the full development of the individual, which in turn reacts back upon the productive power of labour as itself the greatest productive power. From the standpoint of the direct production process it can be regarded as the production of fixed capital, this fixed capital being man himself. It goes without saying, by the way, that direct labour time itself cannot remain in the abstract antithesis to free time in which it appears from the perspective of bourgeois economy… Free time – which is both idle time and time for higher activity – has naturally transformed its possessor into a different subject, and he then enters into the direct production process as this different subject. This process is then both discipline, as regards the human being in the process of becoming; and, at the same time, practice [Ausübung], experimental science, materially creative and objectifying science, as regards the human being who has become, in whose head exists the accumulated knowledge of society.”