Is the Chinese economy as efficient in 2019 as it was in the mid-1980s?

Quite an extraordinary claim

This Barron’s article (China’s Slowdown Is Only Just Beginning) starts by laying out its message in clear, unequivocal terms:

“China’s long boom is over. Persistent weaknesses in productivity growth and a looming demographic catastrophe will hobble the country for decades to come.”

It goes on to make some bold and fairly extraordinary statements and predictions:

“According to an estimate from Harry Xiaoying Wu of Japan’s Hitotsubashi University, China’s underlying efficiency has not improved at all since the mid-1980s. In fact, he estimates Chinese businesses are now 15% less productive than they were in 2007.”

“China’s vibrant pockets of private innovation have been squeezed for political reasons. While it is possible the political situation could change, and therefore lead to a renewed burst of productivity growth, as in 1978, that is not the likeliest outcome. Zero productivity growth, or even continued declines, are far more likely.”

Over the years, I have developed certain views and mental models in topics that I am interested in, China’s economy being one of them. These views and models have evolved over time as I collected new experiences, data, anecdotes, insights and learnings. An important part of my learning process is seeking out dissenting and alternative views and trying to understand where they come from.

So when I encounter a view or claim that is diametrically opposed to an existing worldview, my ears perk. Especially when they come from relatively reputable sources such as Barron’s (vs. anonymous or otherwise unverified sources).

I was too young to have a good sense of what China was like in the mid-80s but I do remember the time my father made his first trip back to China since fleeing the war-torn country four decades earlier for Hong Kong (followed by Canada and then finally America). A hard-working, mid-level civil engineer who had helped build and maintain airports and highways in the Tri-State area since the early 70s, he was invited to China in 1986 to give a talk about something called “Fly ash”. I still remember the handwritten paper and slides he put together in preparation for the trip.

Fly ash is a byproduct of burning coal and a critical ingredient in improving the strength and durability of concrete. The technique of adding fly ash to concrete to improve building structures had been around since the early 20th century. Indeed, the Romans had figured out the benefits of adding volcanic ash to concrete nearly two millennia earlier.

Now stop here and ponder this thought for a second: In the mid-80s, Chinese builders were trying to figure out how to utilize fly ash in concrete, a relatively basic technique that others had figured out decades or even centuries earlier.

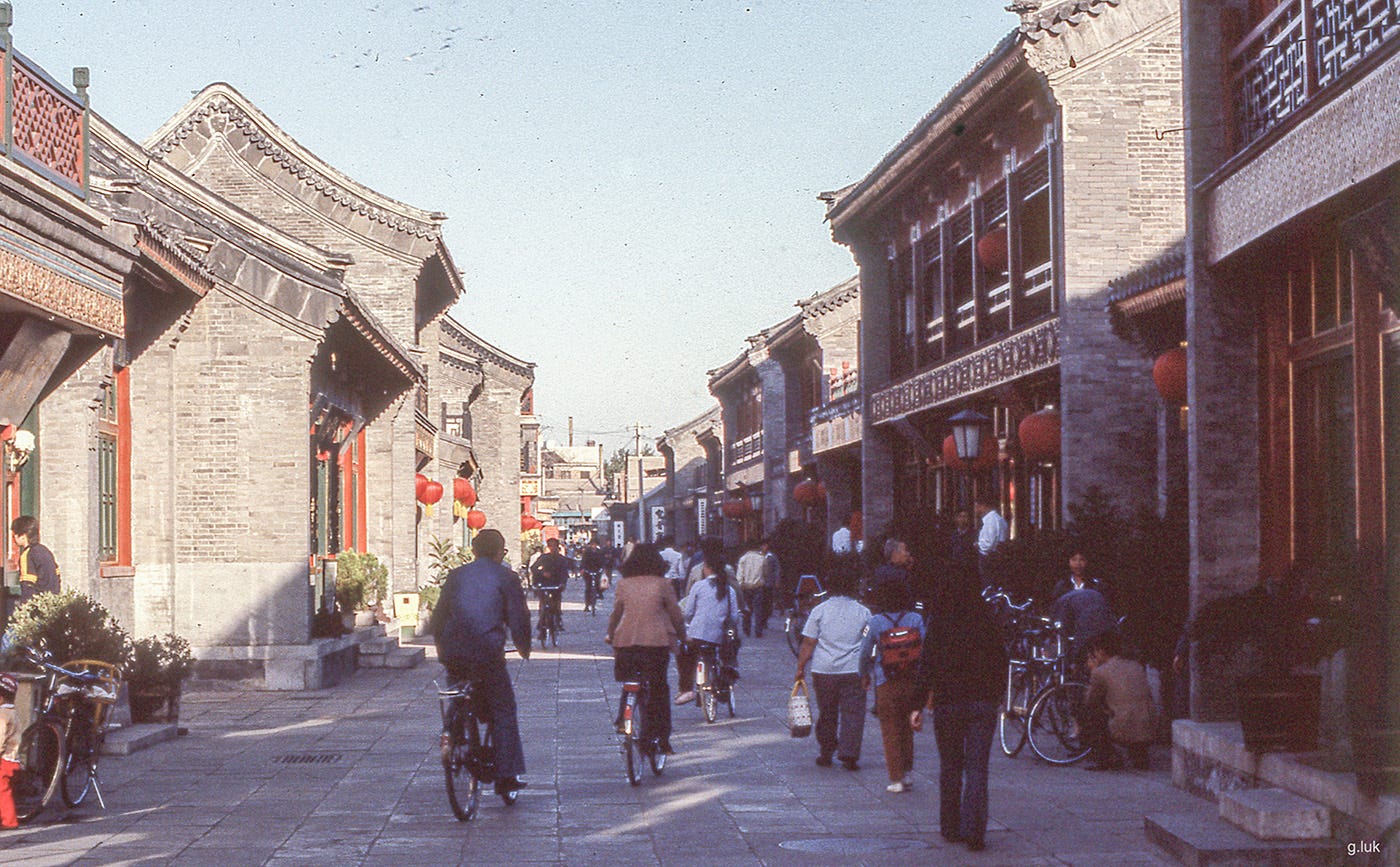

While this is just a simple anecdote, it remains a visceral reminder to me of exactly how undeveloped China was in the “mid-1980s”.

So when a writer at Barron’s makes such a bold and unequivocal statement about how the Chinese economy today — in 2019 — is essentially operating at the same level of fundamental efficiency as it was when Dad gave his lecture in 1986, I am really, really curious about how he came to that conclusion.

As Carl Sagan once quoted, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence” and this aphorism is quite applicable here.

This means rolling up our sleeves and doing a deeper dive into the article, to see if the evidentiary standards hold up to the high standards demanded by the extraordinariness of the claims.

The article’s claims around China’s historical productivity (or lack thereof) rely almost exclusively on the work done by Harry X. Wu, the economics professor referenced in the earlier quote. The article specifically links to a paper released by Professor Wu in December 2017 that challenged mainstream views that something called “Total Factor Productivity” accounted for around 40% of China’s growth since the early 1980s.

This was not the first time Professor Wu made this claim. If you go back and review his body of work, you will see how it is a recurring theme that goes back to the mid-90s. But before we get into Professor Wu’s analysis, let me try to explain some of the basic ideas behind this concept of economic productivity.

Economists believe that there are three fundamental factors or inputs that go into growing an economy:

Labor — the number of available workers

Capital — machines, equipment and investments

Productivity — the efficiency of labor and capital

In other words, economies can grow by (i) adding more people, (ii) investing more in capital that delivers future benefits and (iii) getting more efficient use out of the same labor and capital inputs.

Labor growth is really easy to measure — you just need to count the number of productive workers in an economy.

Capital growth is a bit harder to measure — because this involves some level of judgment. For example, machines wear out or “depreciate” over time. Eventually, they break down completely and need to removed from the aggregate pool of capital stock. Estimates on “depreciable life” are not always the most accurate.

Productivity is the most difficult one to measure directly. It is hard for individuals to accurately track how productive they are on a year-over-year basis. Imagine how difficult it is to do a bottoms-up productivity assessment for an entire economy.

That is why economists have historically measured productivity as the residual or “plug” number after measuring the aggregate output of an economy (i.e. GDP, or gross domestic product) and stripping out the pieces that are attributable to labor and capital. In other words, even though it is supposed to represent an input factor — representing technological or process improvement — it is usually calculated indirectly as an output of the first two.

Despite the difficulty inherent in measuring it, productivity is actually by far the most important part of economic development. On its own, growth via labor pool increase does not improve individual quality of life (i.e. on a per capita basis). Growth via capital has limits due to diminishing marginal returns on incremental investment — over-investing can actually harm long-term economic growth. Productivity growth — i.e. getting better at producing stuff with the same inputs — is ultimately the difference between economic success and failure.

Robert Solow, the Emeritus Institute Professor of Economics at MIT, won a Nobel Prize in Economics in 1987 for his pioneering work on this topic of the relationship between labor, capital and productivity. This “Solow” model is one of the fundamental Big Ideas in modern Economics.

Over time, others have built on top of the “Solow” model. Professor Harry Wu was one of them.

In his December 2017 paper, Professor Wu tries to explain how productivity growth has lagged in China, particularly if you try to isolate out the impact of ICT (Information and Computer Technology).

After parsing through all of the economics jargon, fancy-looking formulas and a cursory review of the underlying datasets, I found two major issues with the analysis:

Professor Wu uses a non-standard set of data that has been “adjusted”, rather arbitrarily it appears. This results in overall growth that is around 3% lower than official GDP measures.

Professor Wu then takes this lower GDP figure, and following the basic premise of the “Solow model” subtracts out capital and labor input growth to arrive at a low or even negative residual. This “Solow residual” approximates productivity’s contribution to growth.

When most economists look at the Chinese economy from the lens of the “Solow” model, they get to around 12% growth per year over the first three decades of reform, with 2% from labor pool increase, 6% from capital and the residual 4% from productivity improvements.

Professor Wu is saying that he doesn’t trust official numbers and according to his data China’s actually only grown at 9% per year. So if you subtract away the 2% labor pool increase and 6% contribution from capital, productivity contribution was a mere 1%. And by the way, most of this productivity contribution happened in the first decade of reform — hence the idea that China’s economy has relied on only labor and capital since the late-80s.

But this logic is circular in nature. Professor Wu prepares adjusted data to “prove” that China’s growth lags the official figures. Much of the adjustment is coming up with his own assumptions for certain key variables — for example, as per the quote below, he makes a “far-reaching yet apparently arbitrary” assumption that reforms in the 1990s added only 1% to services growth.

In other words, by making some basic up-front assumptions that are extremely conservative, you have back-solved the original hypothesis in a circular and non-convincing way. This is a classic case of “garbage in, garbage out”.

On top of this, he makes the assumption that the entire growth gap is attributable to the productivity variable in the Solow model. Moreover, the logic of attributing the entire gap to productivity shortfalls — as opposed to also making adjustments to capital measurements — remains unexplained.

And it is not just me. Others have questioned the validity of Professor Wu’s research over the years. From an Economist article in 2014:

At the pessimistic end of the range is Harry Wu, an economist who has devoted much research to the shortcomings of China’s official economic data. He finds that since 2007 TFP has actually been a drag on the economy, denting growth by about 0.9 percentage points a year …

… but the process requires several accounting somersaults. Assumptions are needed about, among other things, the size of the capital stock, the rate of capital depreciation and the level of workers’ education. Mr Wu does not trust official GDP figures and so constructs his own. Because his estimate of average annual growth for 2008-12 (6.5%) is dramatically lower than the official figure (9.3%), his calculations yield a negative Solow residual. Productivity, in other words, appears to have gone into reverse.

This conclusion looks too gloomy. For one thing, there are problems with Mr Wu’s own numbers. He relies on a selective sampling of official data and applies far-reaching yet apparently arbitrary adjustments to them, assuming, for instance, that reforms in the 1990s added only 1% to services growth. Many other economists see problems with Chinese data—lumpy growth figures are often smoothed, for instance—but not enough to justify such extensive revision, especially during the past decade when there has been a proliferation of data from China’s trading partners that can be used to verify the Chinese numbers.

Carsten Holz, an economics professor at Hong Kong University of Science & Technology, used to work closely with Professor Wu but no longer does after repeated intellectual disagreements:

Mr Wu initially mentored Mr Holz but their intellectual dispute later caused the two to fall out with each other.

“It got to a point where Harry Wu wasn't talking to me and wasn't citing my work,” says Mr Holz. “I didn't agree with his work. It just didn't convince me. I thought it was actually wrong.”

Regardless of where you stand on the reliability of Chinese GDP growth figures (some of my own thoughts here and here), at a minimum it is clear that there is controversy around Professor Wu and his approach. His methods and conclusions tend to fall on the very extreme end of the spectrum when it comes to consensus views on Chinese economic growth. To me, his work does not qualify for the extraordinary standards demanded of such extraordinary claims.

That is why it is quite shocking to see a seasoned journalist make such bold statements on the basis of such a wobbly foundation, without providing any context or background. Instead, Professor Wu’s paper is taken as definitive “proof” of the main point of the article — that China’s growth has been a mirage of favorable demographics and extreme capital allocation, not productivity, and because of this it is close to running out of steam.

In the article, there is no mention of the debate, the controversy or the fact that Professor Wu represents a rather extreme, minority view. There does not appear to have been any effort made to questioning the underlying assumptions that went into the paper. Instead, it has been packaged for Barron’s readers as unvarnished “truth” from a credible, academic source.

This illustrates one of the big problems in journalism today. It is very easy to find somebody out there with believable credentials to say something that supports any view, no matter how extreme. Indeed, there is a veritable cottage industry of academics and analysts that specialize in offering their extreme views. It is much harder to get to the bottom of what is going on, because the truth is often much more nuanced, complex and unclear.

That is why the challenge of getting to that truth rests on us, the readers. We have an obligation to not just take everything we read (my stuff included) as unvarnished truth, but to dig into the story, the analysis and the logic. This means diving deeper into sources, questioning the key points and trying to improve our understanding of complex topics so we can ultimately form our own informed views.

Tying things back to the original question: Yes, the claim that Chinese economic growth since the mid-1980s has been driven entirely by labor and capital increases with zero productivity improvement is ludicrous and qualifies as an “extraordinary” claim, one that requires extraordinary evidence to back it up.

This is not one of those things that you really need to over-analyze. By simply looking outside the window and seeing what China looks like today vs. thirty years ago should be self-evident enough.

Actually, we don’t even need to go that far back. Just looking at how life has changed for the average Chinese person in the last ten years is sufficient:

Putting a connected device in the pocket of the vast majority of China’s population that is millions of times more powerful than NASA’s entire computing power in 1969

Moved from a cash-dominated economy to a digital-payment dominated economy — massive reduction in transaction costs + high-quality data that can be used for BI and other applications

Built the world’s largest online e-commerce market and all of the associated logistics infrastructure

Connected all the major cities with a high-speed rail system and building modern metro systems in most large ones

Built out hundreds of gigawatts of solar and renewable electricity capacity

Etc.

Are you really going to sit here and essentially claim that none of these things had any positive impact on Chinese economic productivity?

My response to the article is, “Sounds like an interesting thought, but you’re really going to have do a lot better and find evidence that is far more extraordinary than what you have presented to convince me”.

This was originally published on Quora in January 2019.