Privilège exorbitant

Rising costs to our manufacturing sector of running the world's reserve currency

Dyadic nature of exorbitant privilege

Some consensus is forming on the pros and cons of the U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s reserve reserve currency. Here, Brad Setser who provides some of the most insightful and matter-of-fact commentary and analysis on the sometimes-controversial topic, outlines this dyadic phenomenon:

One of the benefits is having what is essentially a a no-limit credit card that permits the United States to borrow at low rates. In 2019, I wrote about this as part of a piece explaining why the U.S. had such a high trade deficit. But having the world’s “Most Amazing Credit Card” comes with drawbacks, including the ease with which policymakers can stimulate their way out of economic crises like the recent global pandemic.

More significantly, as Brad alludes, this exorbitant privilege also comes with less control over bilateral exchange rates, which has contributed to a long-deteriorating comparative advantage in domestic manufacturing.

Mercantilism and the “East Asian development model” playbook

For many decades, Japan and the “East Asian Tigers” have used this weakness to develop their domestic manufacturing sectors. Japanese industrial policymakers “pioneered” the use of high trade and current account surpluses to turbocharge their manufacturing sectors through the early 80s.

This led to rising trade tensions that eventually spilled out into the “first” trade war between the United States and Japan. Fortunately (for the United States), we had geopolitical leverage over Japan and put it to use, forcing Japan to allow its currency to appreciate in 1985 Plaza Accords.

The “East Asian Tigers” of Taiwan and South Korea followed in Japan’s footsteps. Taiwan has long (and continues to) run one of the most mercantilist economies on the planet with current account surpluses north of 15%. South Korea started generating substantial large trade surpluses after the Asian Financial Crisis. Both relied on exports — underpinned by demand from the United States, in particular — to drive the development of their advanced industries.

Then China came along and continued this now-seemingly standard maneuver of the “East Asian development model” playbook to drive its early industrialization. Of course, the difference here is China’s scale: its population is more than seven times the combined populations of Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

China’s current account surplus rose to over 10% of GDP on the eve of the Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”). The GFC itself was in part triggered by rising financial imbalances caused by rapidly rising borrowing of U.S. treasury bond and agency debt, which suppressed interest rates with the now well-known downstream effects with subprime securities.

This triggered painful global adjustments with a sharp economic downturn in the developed world and export factories shutting down overnight in China, leading to a large shift in economic resources to its housing and infrastructure sectors.

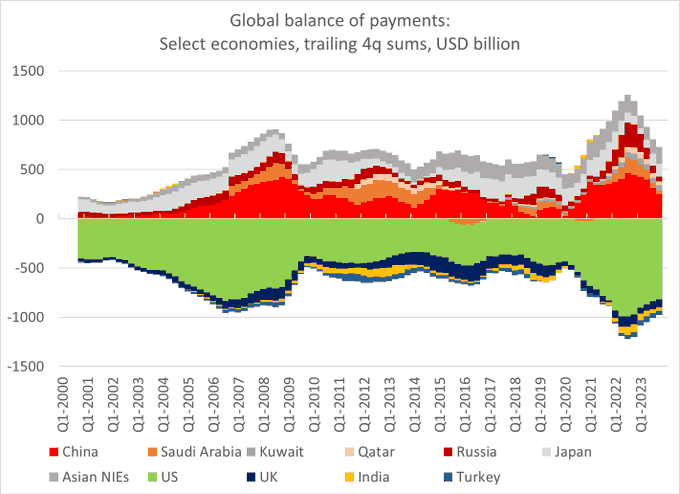

For the next decade through the end of the 2010s, there was a respite in the growth of the U.S. trade deficit, as you can see with the green shaded area in another one of Brad’s amazing charts:

However, the underlying issue had not really gone away. Moreover, beneath the seemingly calm waters of a stable trade deficit churned one of the most under-appreciated macro factors of the last two decades. The United States was turning from one of the world’s largest oil importers into an exporter:

Declining trade deficits with the oil-exporting countries of the world meant that the deficit in manufactured goods continued to rise during this period, even as China turned inwards to focus more on its domestic economy, contributing to further deterioration of onshore manufacturing. In the most recent iteration of “Dutch Disease”, a beleagured American manufacturing sector had to deal with even greater support for the appreciation of the U.S. dollar.

This came to a head with the Global Pandemic, when we discovered just how much we relied on the supply of manufactured goods from the Asia-Pacific region, especially China. Imports of manufactured goods grew while “exports” of travel and education (two of the largest imports by China) came to a standstill. The trade and balance of payments deficit once again ballooned.

Further exacerbating trade tensions has been the rise of Chinese advanced manufacturers. While everyone was distracted by the pandemic and China’s emerging property woes, the clean energy triumvirate of electric vehicles, batteries and renewables were incubating within the comfortable confines of protective Chinese industrial policy. Now, as we have seen exemplified by rapidly rising vehicle exports, Chinese advanced manufacturers have emerged as ferocious global competitors.

Whither the almighty dollar

Compared to Japan in the 1980s, the United States has minimal leverage with China today. At that time, the U.S. was Japan’s largest car market. Chinese automakers are de facto banned and have minimal presence in the country. China’s domestic markets in most manufactured goods categories are much larger than the United States or even the combined markets of the G-7 in some cases. Notably, the United States has its largest military forces stationed in Japan. Further, frosty geopolitical and trade tensions have made it difficult to even have conversations.

Since it is clearly out of the question to negotiate or cajole China into moving away from a weak RMB policy, what options does that leave us? Other countries that have more control over their currencies can weaken them. That is what has happened with the Japanese Yen in recent years. But our hands are mostly tied because of this exorbitant privilege.

I do not have a good answer here except to say that now seems as good a time as any to consider the pros and cons of keeping this status, with manufacturing competitiveness in the front of our minds.

Brad Setser seems to me to be as good as we've got with the chops to talk to the PBOC, and I have begged him in the past to do so.

If the White House authorized him, I am sure the PBOC Governors would love to spend a morning kicking around ideas and timetables for currency reconciliation by say, 2030.

Naga happen.

We're too dumb to talk, too gutless to fight, and too committed to a discredited economic fad.