Why does the US have such a high trade deficit?

Because our economy has gotten more advanced over time

The trade deficit is high because our economy has gotten more advanced over time.

At first glance, this may sound counter-intuitive, but hear me out:

The “stuff” we produce today is more sophisticated than before. Generally, this means that it is by nature less physical and more intangible (i.e. software, services and intellectual property). Instead of producing physical things with our hands and physical labor, the value has shifted to producing intangible things with our minds and creativity.

Our economy has gotten more specialized over time. Instead of handling every single piece of the manufacturing process, we have broken it up into a series of discrete steps and analyzed each step to decide whether certain activities are worth more of our time to handle than others. As above, this typically means activities where we use more of our brains vs. our hands. To free up resources on the higher value-add activities (which includes living more comfortable lives), we have diverted some of the more labor-intensive activity to our trading partners.

As our economy has become more sophisticated, traditional metrics like “trade deficits” are less representative of how real economic value flows in international trade. To gain a more holistic view of it, we need to understand something called “Balance of Payments” or “BoP”.

Even BoP is unable to fully capture all of the economic value flows. The increasingly intangible nature of the products and services we produce has led to a rise in the artificial shifting of trade offshore for tax purposes, to the point where goods and services created by Americans and sold to our trading partners do not even show up in our international trade accounting.

After accounting for all of these points — which I will explain in greater detail below — it is important to note that we do still run a fairly large deficit with the rest of the world. However, this number is much smaller than the headline figures that are often bandied about.

Also significant is the concept that we need to run some level of deficit with the rest of the world as part of the U.S. Dollar’s role as the global reserve currency, which turns out to be a very powerful and highly advantageous tool at our disposal.

International trade is complicated and not the easiest thing to understand but I will try my best to explain using real-world examples. I believe it is worth taking the time to think about this topic so we can be better equipped (as a society) to make smart decisions when it comes to trade policy, especially at this critical juncture in history. The decisions that we make today will have long-lasting ramifications that will impact us for decades to come.

To start, we will examine why the traditional “trade deficit” is really just one piece — that is becoming less significant over time — of international trade. To understand why, we need to get a little smarter on the intricacies of international trade and Balance of Payments accounting.

Then, we will take a look at how the increasing sophistication of our economy has shifted value flows within BoP from “trade deficits” to other categories. We will also take a look at how certain trade flows aren’t even captured due to tax tricks that multi-national corporations utilize to minimize taxes. Finally, we will look at how this impacts our thinking on trade policy.

Specifically, we will examine this question through the lens of the U.S.-China bilateral relationship, as it is one of the most important economic relationships in the world today and one that has been dominating news headlines in recent months.

Welcome to class, my friends. It’s time to put on your learning caps. There might be a pop quiz at the end.

BONUS: There will be guest appearances by Alec Baldwin and Emily Ratajkowski. And to spice things up even further, you are encouraged to channel the voice of Ben Stein, who plays an economics teacher in Ferris Bueller's Day Off:

“Balance of Payments” 101: The Current Account

“Balance of Payments” represents … anyone? anyone? … money flows coming in and out of a country for things like international trade and cross-border investment.

At a very high level level, one can think of this as all of the various cashflows going in and out of your banking and investment accounts, perhaps as captured in an online personal finance service such as Mint.

One difference is that most of the money flows for a household take place externally whereas for a country — especially a large one like the United States — most economic activity takes place internally, i.e. within the borders.

BoP does not measure activity that does not cross the border. So if the foreign subsidiary of an American company sells in that foreign country, and decides for whatever reason not to send the profits back to headquarters, this activity is not captured in the BoP (at least not directly).

In other words, BoP represents only a small percentage of the economic activity of a large country like the United States — and it only measures the economic activity that officially crosses the borders. This is a really important idea that will become more evident as you read further.

Within the Balance of Payments, there are two major types of money flows:

Current Account — regular, ongoing economic activity like trade and income from foreign investments. In the household example, this is analogous to your salary, business income and income on passive investments/assets like dividends and interest income.

Capital/Financial Account — investment-related economic activity like investing in foreign subsidiaries, issuing debt, etc. This is analogous to investing in stocks, or buying a house (both the equity down-payment as well as the mortgage you take out).

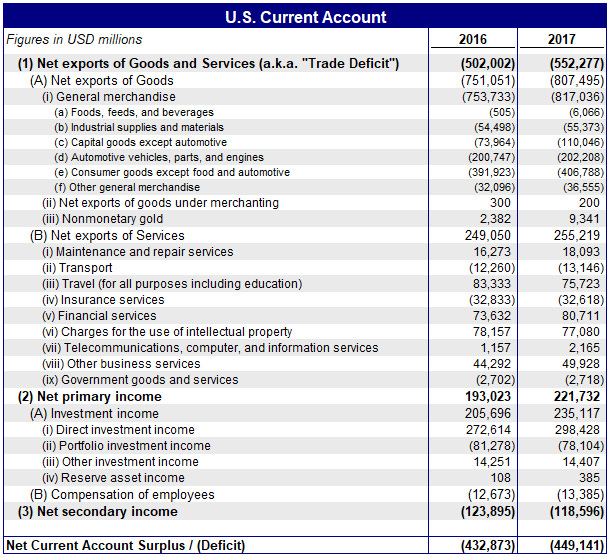

We will first go through the Current Account. In 2017, the U.S. ran a $449 billion deficit on its Current Account — this is the number in the bottom-right corner of the table below. (Note: This is an important table; I will refer back to it a number of times throughout the discussion.)

Outside of the trade in goods and services, the other big components are “Primary Income” (Line 2) and “Secondary Income” (Line 3). These categories represent, among other things, income generated by foreign subsidiaries, investment income generated on holdings of foreign securities, salaries paid to expatriates, remittances from foreign labor, etc.

The other side of the BoP equation is the Capital/Financial account. We will get to this later but for now, let’s look at how the value flows from international trade are captured by the BoP. Specifically we will take a look at how our evolving economy has shifted certain values within the various Current Account line items.

Economic Trend #1: Paper to Software

In 1992 cult classic Glengarry Glen Ross (adapted from the 1983 Pulitzer Prize-winning play), Alec Baldwin plays the role of an experienced salesman who is tasked with motivating a few low-energy brokers in a sleepy branch office of a real estate firm. In one of the most electric single-scene performances in modern film history, he delivers a masterful and vicious monologue on the art of selling. He is our first guest lecturer.

As you watch the monologue, pay attention to all the various selling tools of the day — index cards with the sales leads, spinning Rolodexes, poster advertisements on the walls, office supplies, landline telephones, and motivational prizes like cars and steak knives. (Note: You may have to watch a couple of times because Baldwin really does deliver a captivating performance.)

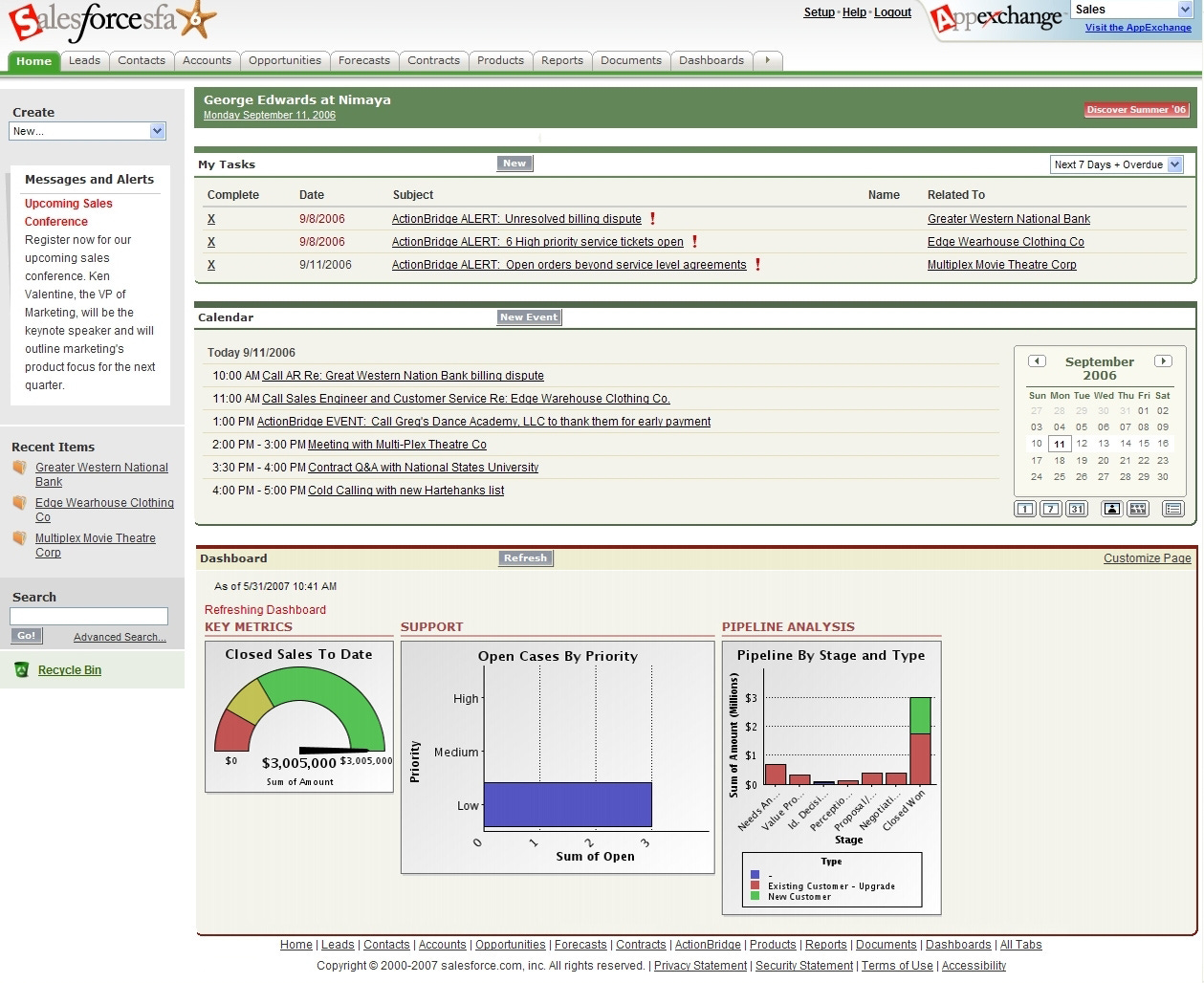

Seven years after the film was released, software executive Marc Benioff left Oracle to start a new type of software company, one that delivered its services through the browser on an on-demand basis instead of having to be purchased up-front and delivered as an application on a PC or workstation. The first business department that it targeted was the sales department and was named, aptly, salesforce.com.

Today, its software powers everything from selling, marketing, customer service to communications for thousands of businesses with operations spanning the globe.

In just a few decades, the shift from the “pen and paper” era of Glengarry Glen Ross to sales automation software delivered as a service represented a shift from the physical world to the intangible. And the same shift can be seen in countless other industries and businesses across the globe.

On the BoP, trade of physical goods is accounted for differently than trade of intangible goods. This is rooted in history.

When modern nation-states started to keep detailed records of their international trading activity, essentially all trade was comprised of physical goods. Physical goods would cross borders and moneywould be exchanged. Nation-states were particularly interested in keeping detailed records of international trade because it was one of the most popular ways to raise money to fund governments and armies. For example, in 1915, approximately 30% of U.S. Federal Government revenue was funded through customs duties compared to 6% from the newly instituted income tax.

As the economies and technology advanced, it became possible to start trading non-physical things. For example, let’s think about leisure travel. Back in 19th-century America, round-trip international tickets were not common. Usually international travel was a one-way ticket, i.e. permanent immigration and settlement. But improvements in the speed and cost of new transportation options opened the door to leisure travel. Today, leisure travel is one of the larger intangible services that is traded between countries. On the BoP statement, international travel is accounted for under Line 1.B.iii “Net Exports of Services / Travel” and contributed a $76 billion surplus to the American economy in 2017. Living in Lower Manhattan, which draws over 14 million visitors a year, many of them international, I witness this on a firsthand basis every day.

Going back to our Glengarry Glen Ross example, whereas Rolodexes (or is it Rolodices?) and steak knives would show up on Line 1.A. on the table above (“Net exports of Goods”), software and intellectual property would show up elsewhere, possibly under Line 1.B “Net exports of Services”.

The good news is that when most people refer to the overall “U.S. trade deficit”, they refer properly to “Net exports of Goods and Services”. (Unfortunately, “most people” does not include the Leader of the Free World as we will see down below.)

For example, from a February 2018 Wall Street Journal article:

The U.S. trade deficit in goods and services grew 12% last year to $566 billion, its widest mark since 2008 and a challenge for President Donald Trump, who has pledged to re-balance the nation’s books with the rest of the world.

However, I have seen issues arise when when we start talking about bilateral trade surpluses/deficits — such as the one between the U.S. and China — where they only focus on the goods portion. For example, from the very next paragraph in that article (emphasis mine):

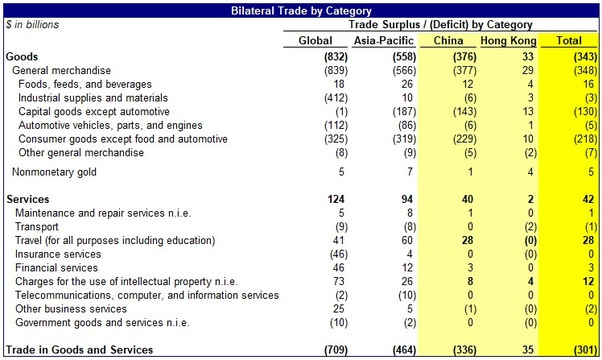

The goods deficit with China alone rose 8% during Mr. Trump’s first year in office to a record $375.2 billion, or nearly half the total global gap between U.S. imports and exports, the Commerce Department said Tuesday.

By including services in the first paragraph and ignoring it in the second, this presents a misleading picture of the U.S.-China trade relationship. Specifically, it overstates the “true” deficit we have with China. The slightly better figure to use would be $336 billion, which nets out the positive surplus that the U.S. gets from the trade of services with China.

Further, since much intermediate trade goes to China via Hong Kong, an even better figure to use would be $301 billion, which factors in the trade surplus the United States has with Hong Kong — which is accounted for separately from Mainland China.

But as I will explain in the next section, due to the increasing specialization in global supply chains, even this $301 billion figure over-states the “true” value deficit between China and the United States.

Economic Trend #2: Global/Special-ization of Supply Chains

Where does the money I pay for an iPhone go?

In this earlier answer, I took the reader on a journey around the world, from the initial purchase of an iPhone in London, to its manufacture in China, to its original design in California. At the end, I summarized by showing how the economic value of a £999 iPhone is split up between the various contributing economies.

One of the key takeaways in the answer — which should be fairly evident after all of the frequent flier miles accumulated on the journey — is that the global supply chain today has gotten really complicated. Components are designed in one place, manufactured somewhere else and shipped to a third place to be assembled by machine-assisted hand. IP is invented in one region, domiciled in another (for tax purposes) and monetized in an increasing number of creative ways.

This was, of course, very different two centuries ago, when “goods” were largely manufactured from start to finish in a single economic zone or region. Think back to the Triangular Trade of the 18th and 19th centuries when manufactured goods would flow from industrialized England to the Americas, raw commodities would flow from the Americas to Europe and, of course, the despicable trade of humans from Africa to the Americas:

Because of this, trade surpluses and deficits back then were pretty accurate reflections of the true economic value flows between nation-states. But as supply chains specialized over time — driven by a massive reduction in friction costs, primarily in the form of lower tariffs and lower transportation costs — international trade accounting has had a tough time keeping up with the changes. This is especially true when applied to measuring bilateral trade relationships such as the one between the U.S. and China.

The particular issue here is that China captures only a fraction of the economic value of the (primarily) physical goods that it exports to the United States. But from an international trade accounting and BoP perspective, “Made in China” gets full credit.

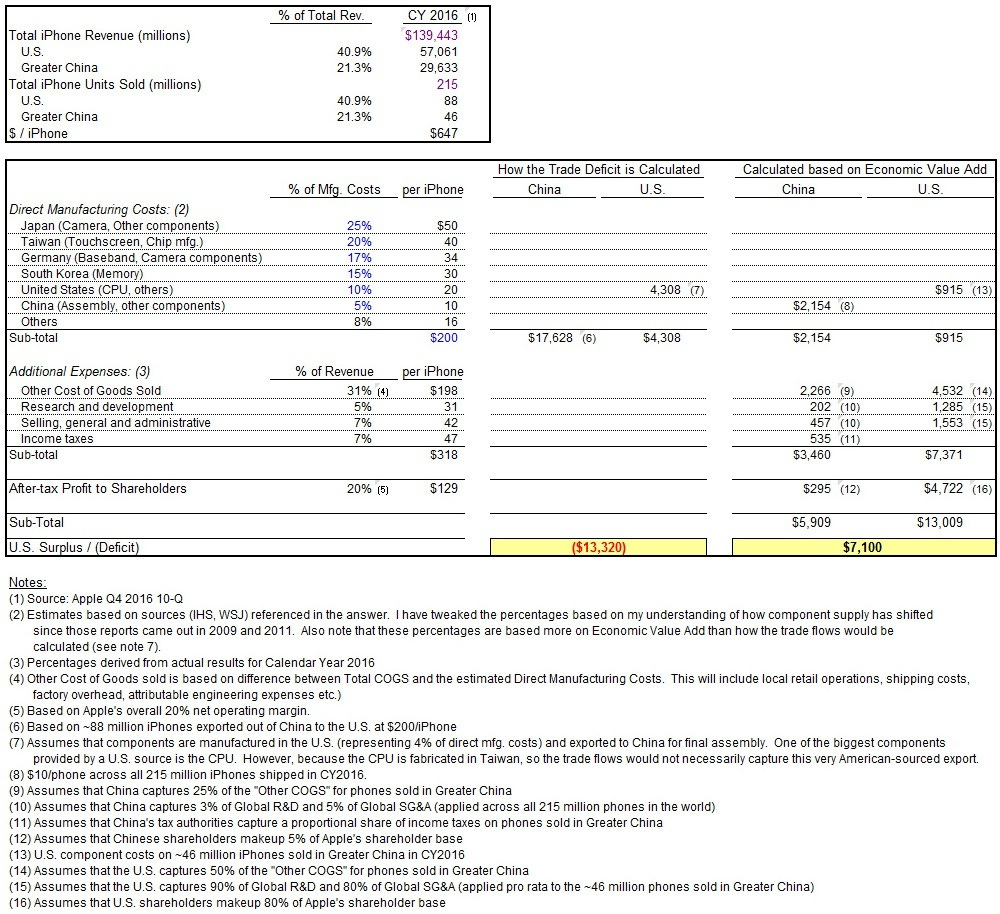

For example, I showed in the iPhone example how China captures at most one-eighth of the production value (BOM) of an iPhone … and an even smaller amount of the retail value:

It needs to import dozens of expensive components from places like South Korea, Taiwan, Germany, Japan as well as the United States.

It needs to import crude oil from Saudi Arabia to power the trucks and ships that ferry the components and finished goods back and forth.

It needs to import advanced industrial equipment to perform many of the intricate manufacturing steps needed to produce hundreds of millions of iOS devices every year.

Despite all of the impressive advances the Chinese economy has made over the years, it is still really only capturing a thin layer of value-add of the iPhone, as well as many other common export categories.

This shows up in international trade accounting in the large trade deficits that China runs with many of the upstream component and intermediate goods manufacturers. It imports sophisticated capital equipment from places like Japan and Germany to build out its factories. It imports energy and commodities from places like Australia and the Middle East to power its manufacturing operations. It imports the high-value components that make up the innards of the finished products that it assembles.

In other words, much of its bilateral trade surplus with the United States is merely passed along to other countries. We can see this in some of the large bilateral trade deficits China has with other countries:

One quick way to gauge how much pass-through trade surplus China takes on from the United States is to look at Balance of Payments data from its perspective. In 2017, China generated a Current Account surplus of $165 billion, or around 1.4% of GDP. This was down from a peak of $421 billion in 2008 on the eve of the Global Financial Crisis, which represented almost one-tenth of China’s (much-smaller) GDP at the time.

The difference between the $336 billion and the $165 billion is a rough approximation of the “pass-through” trade surplus to other countries and $165 billion is a much more accurate reflection of the true economic value flows.

(Note: One side takeaway from the chart below is that China is far, far less reliant on a mercantilist, export-centric economic development strategy today compared to a decade ago.)

On top of this, we also need to remember that the United States is not the only trading counter-party that China runs a large trade surplus with. In particular, it runs large trading surpluses with the U.K., India and much of Europe (ex-Germany). In other words, perhaps only 60–70% of its Current Account surplus is actually attributable to the United States.

But even the more holistic Current Account metric fails to capture all of the international flows of economic value. This because in many cases, the money flows from U.S.-produced IP never even directly crosses the U.S. border. Value is still captured by Americans but mostly indirectly and spread out over a long period of time. To see why, we need to look into international tax accounting and the Capital/Financial Account portion of Balance of Payments ledger.

Economic Trend #3: The Absurdity of International Taxation

How will the race to 5G dominance play out between Qualcomm and Huawei?

Here I discuss how Qualcomm built up a massive patent portfolio over the years and monetized it largely by collecting licensing fees from smartphone and network equipment OEMs. Like Apple in the earlier example, much of this IP sits offshore for tax reasons.

If the end customer is American, the money flow will show up through the importation of what is typically a physical hardware device, like an iPhone. Because of some of the quirks in BoP accounting I described above, even though most of the iPhone’s IP originates from the U.S., it still ends up contributing to our bilateral trade deficit with China.

This absurdity can be seen in an example from an earlier post that shows how this might work for an iPhone:

Things get even more non-sensical when the end sale takes place outside the United States.

For tax reasons, the IP is domiciled offshore, in a tax-friendly jurisdiction like Ireland. When Apple sells an iPhone to an end customer in London, the profits are collected offshore. None of the money ever flows back “onshore” to the United States, lest it be subject to something called a “repatriation tax”. (Note: this may change with the new 2017 tax laws but is relevant for all of the data we are looking at here; see Explanatory Note i)

As such, even though this is clearly an export of American IP, much of it is not even captured in any of the BoP line items.

To be fair, a small portion of it would show up in Line 1.B. “Exports of services”, likely under the “charges for the use of intellectual property” sub-category. This is because there are rules around something called transfer pricing that govern intra-company asset transfers:

For example, say Qualcomm engineers in San Diego come up with a new invention and patent it. The company’s tax accountants want the IP to sit in a tax-friendly place like Ireland so it needs to arrange the transfer of IP. It must follow some transfer pricing rules, which means selling the IP at some nominal “cost-plus” markup. It would recognize a nominal amount of onshore U.S. profit, on which it would pay a small amount of tax. From Ireland, Qualcomm can sell the IP globally and pay a much lower tax on profits than it would have if it had sold it from the United States.

(Note: I am not an international tax accounting expert and I might be missing some steps and/or jurisdictions but this should be directionally correct based on discussions I’ve had with actual experts.)

The net effect is that international sales of this IP do not generate any onshore money flows and, accordingly, are not calculated in the U.S. BoP accounts. But this does not mean that we are missing out on the benefits of the trade. It just shows up in different line items and is spread out over time. To find out how, we now have to learn about the Capital/Financial Account section of the BoP.

“Balance of Payments” 102: The Capital/Financial Account

We’re back in the classroom, students. Kudos to all of you who decided to come back for second semester.

I’ve been writing this darn thing so long that I’ve aged quite a bit since we last met:

As you might guess from the name, Balance of Payments ultimately needs to … anyone? anyone? … balance.

So if you run a large Current Account deficit, the deficit will need to be funded somehow. If you run a large Current Account surplus, you will need to send the surplus capital outside the country. These transactions are captured in the Capital/Financial Account.

As we have been running large trade deficits for most of the last three decades, as Warren Buffett likes to say, we have been issuing “claims checks” to our foreign trading partners to pay for all of the extra stuff that they send us.

These claims checks generally come in two forms: debt and equity. The debt is primarily made up of U.S. government bonds, debt backed by various forms of real estate, and debt issued by our corporations. The equity is made up of publicly traded equity as well as private (non-traded) investment, also known as “direct foreign investment”.

Over the years, our foreign trading partners have accumulated quite a large stash of claims checks. But how much exactly?

The U.S. Treasury releases monthly data on the market value of traded securities held by foreigners and the number is around $19.0 trillion as of September 30, 2018 This figure is comprised of:

$6.6 trillion in U.S. Treasuries and Agency bonds

$3.8 trillion in U.S. corporate bonds

$8.6 trillion in U.S. equities

$19 trillion is a whole lotta skrilla.

But this figure needs to be reduced, or netted off, by foreign assets held by Americans of around $11.8 trillion, comprised of:

$2.9 trillion in government and corporate bonds

$8.9 trillion in other securities (e.g. corporate debt, equities)

These figures exclude foreign direct investment (FDI) but the good news here (for those of us who are less mathematically inclined) is that outbound FDI stock is almost exactly equal at $6.4 trillion each.

So, netting everything out, foreigners own about $7.2 trillion more of America than Americans own of the rest of the world. As a sanity check, this number ties (roughly) to the accumulated Current Account deficits that we have generated since 1999 (which was about the time we started to generate large deficits) of $9.3 trillion. (Note: it will not be exact because there are other line items in the Capital/Financial Account like straight-up currency and direct loans, as well as a plug account “statistical discrepancy”).

Also, remember all of that cash that never made it onshore because American multi-nationals (“MNCs”) were trying to avoid taxes? This cash (and re-invested foreign profits) — some $2.6 trillion of it sitting in foreign subsidiaries of the MNCs — is part of this $7.2 trillion net figure.

If MNCs had been repatriating their overseas profits as it was earned, it would likely reduce our Current Account deficit by at least $150 billion per year. It supports the market/intrinsic valuation of the companies, and the mostly American shareholders of these MNCs benefit from this value, but from an international accounting perspective it does not show up directly.

Over the very long run, the benefit will show up in the Balance of Payments accounts, via foreign purchases of equity and securities that have increased in value value over time. But the key point here is that the BoP effect will show up over a long period of time and also be subject to fluctuations in market sentiment (affecting valuation multiples).

Phew! That was a lot of math and big numbers. The good news is that our final guest lecturer has arrived!

Just kidding, we are are not going to talk about Emily Ratajkowski. I just noticed some of you in the back falling asleep and I needed to get your attention because the next point is an important one.

(Note: Yes, I know, that was quite shameless. But before I get inundated with #MeToo hashtags, remember y’all got young Alec Baldwin earlier in the lecture. Not to mention a young-ish Ben Stein.)

Economic Trend #4: The Almighty U.S. Dollar

So … $7.2 trillion is still a lotta skrilla. As a country, you would rather have a net positive international investment position than a negative one. But America has another trick up its sleeve: Our currency is the global reserve currency.

Without getting too much into the details, one of the advantages you get by controlling the global reserve currency is that you end up owning a much more productive pool of foreign assets than foreigners own of you. To illustrate this point, we will make our last reference to Balance of Payments.

Here’s the important table repeated from up above. Line 2 is something called “Primary Income”. Most of this line item is made up of investment income earned on bonds (interest income), stocks (dividends) and foreign direct investment (repatriated earnings).

Despite the fact that foreigners own over $7 trillion more in American assets than Americans own of theirs, the United States generated $222 billion more Primary Income than it exported in 2017. In other words, the mix of overseas assets that we hold is significantly more productive than the U.S. assets held by foreigners.

The main reason for this is that a large portion of the $19.0 trillion in liquid assets held by foreigners is made up of low-yielding U.S. Treasury government bonds. Whereas the majority of liquid foreign assets held by Americans are higher-upside (and often higher-yielding) equities — and even the bonds that they hold typically generate higher yields than U.S. Treasuries. Moreover, American outbound FDI tends to be comprised of more productive business assets while inbound FDI from foreigners includes more passive investments like real estate.

It’s not that foreigners like holding low-yielding American assets. It’s that they are effectively forced to because of the U.S. Dollar’s status as the main global reserve currency. As the de facto global store of value, it becomes the standard place to “park” assets. So when countries like China run massive trade surpluses year after year, they are essentially forced to acquire low-yielding U.S. Treasury assets. As long as the U.S. Dollar dominates global trade, we get to set the rules.

Having your currency as the dominant reserve currency gives you the world’s Most Amazing Credit Card: One that comes with unlimited credit, low borrowing rates and the general right to “not give a f—” when it comes to monetary policy.

Like this, but made out of an Adamantium-Vibranium alloy.

It also has no expiration date — provided you remain the dominant reserve currency. And to remain the dominant reserve currency, you need to be willing to take a leadership role in trade, not turn your back on the world. I do very much hope that we are doing our very best to make sure this card is in our wallet for decades to come.

The Bottom Line: What Needs to be Fixed and How Do We Fix it?

To fix things, we first need to get the facts straight. The problem with our trade policy decision-making today is that we are using the wrong numbers … and this will inevitably lead to the wrong prescription.

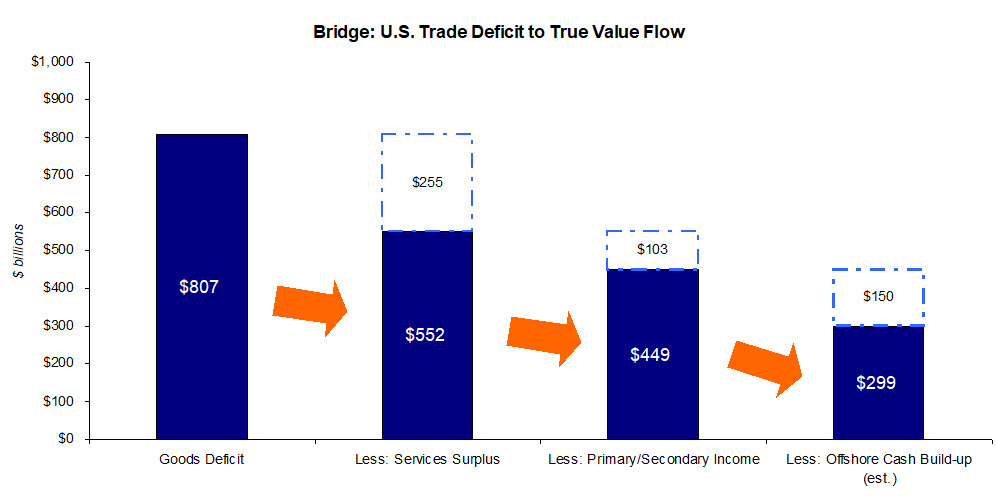

During the 2016 Presidential Debate, Donald Trump said that America had an “almost $800 billion trade deficit”. After becoming President, he has continued to repeat this $800 billion figure ad nauseum.

As I have described above, this number is completely misleading. Our economy is not a goods-based economy, it is a knowledge-based economy and if we account for this, the true deficit is much closer to $300 billion than $800 billion:

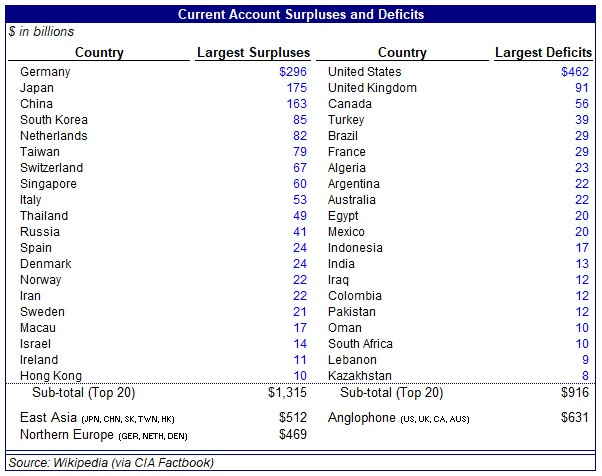

The other problem is that President Trump appears to be almost singularly focused on China for taking our jobs, attributing “$500 billion” of the trade deficit to them. But again, to ground ourselves with the right facts and reality, we need to look at how other countries stack up:

What’s really going on here is that the Anglophone (English-speaking) countries as a group are importing capital (and exporting jobs) to two major economic regions: East Asia and Northern Europe.

China is only part of the issue — it makes up less than one-third of the aggregate “East Asia” surplus. Even more importantly, the labor-intensive jobs that we have lost to China are probably not the ones we want. It’s the high value-add, highly paid knowledge worker jobs that we should aspire to and those are more likely found in places like Japan, Germany, South Korea and Taiwan, not China.

If we look at things on a per capita basis, the contrast is even more stark. At least from the traditional definition of mercantilism, China barely registers.

Note: Data may not sync up exactly with previous table; data was pulled from an older post.

If we put all of our trade policy focus on China, we are going to have a tough time solving the real economic realities that we face.

Now there may be other strategic and geopolitical reasons to focus on China these days and that might very well be the right course of action. But if that’s the case, let’s be up front with ourselves about call a spade a spade. Moreover, enacting trade policy that leads to us pulling back global trade is probably exactly opposite action we should be taking from a geopolitical perspective.

Let’s make decisions based on facts and reality, not falsehoods and blind populism.

Anyone Left? Anyone?

For the few remaining readers who have made it to the end, I have a special bonus for you. Pop quiz time!! (Chill … they are all true-false questions. Plus you were warned at the beginning of class.)

True or False?

The modern evolution of our global economy has meant that the goods we trade are less physical and more intangible.

Traditional ways of measuring international trade flows like “trade deficits” are having a hard time keeping up and accurately representing modern trade.

Using more holistic measures of trade, the U.S. trade imbalance is much smaller than the headline numbers.

In particular, the “true” bilateral deficit with China is significantly lower than the headline numbers once you account for “pass-through” surpluses and the crazy things that companies do to avoid paying taxes.

Running a manageable deficit is not actually a bad thing, especially if it is part of controlling the world’s dominant reserve currency.

It’s important to get smarter on trade so we can avoid enacting stupid trade policy.

Alec Baldwin was pretty awesome in Glengarry Glen Ross.

The U.S. trade deficit is high in large part because our economy is more advanced and sophisticated than ever.

(Answer Key: All TRUE)

Class dismissed.

Explanatory note

[Note i] With the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, changes in the tax system have reduced the disincentive for companies to repatriate taxes back to the United States. While it seems likely that this will change the onshore/offshore cash dynamic, history has shown how the amazing creativity of investment bankers and accountants when it comes to creating new and sophisticated tax structures.

This was originally published on Quora in January 2019.

Simple, they’re DUMB & LAZY.