Does Warren Buffett buy options?

a.k.a. "weapons of mass destruction"

Warren Buffett does not buy options [1] but he might sell you some!

Strange behavior — some would say hypocritical — coming from a man who has in the past derided options and other derivatives as “weapons of mass destruction” that could potentially tank the entire global economy — a prediction which by the way eventually came true in the form of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

But with deeper examination we can gain a more nuanced appreciation for exactly what he meant by this and why he is not being hypocritical, and in the process also learn a little something about options and derivatives.

“Weapons of Mass Destruction”

Derivatives are contracts that derive value from the performance of an underlying security or asset. A simple example of a derivative is a stock option that pays off depending on the price of a stock at a given date. Derivatives can get a lot more complicated as Selena Gomez — yes that Selena Gomez — will explain down below.

In the 2002 Shareholder Letter, Warren Buffett raises an alarm on the increasing usage of derivatives in the financial sector. As always, he doesn’t mince words and gets straight to the point:

Charlie [Munger] and I are of one mind in how we feel about derivatives and the trading activities that go with them: We view them as time bombs, both for the parties that deal in them and the economic system.

A year earlier, Enron had gone bust in the largest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history and derivatives had played a major role in the rise and eventual collapse of the infamous energy company.

In addition, Berkshire’s 1998 acquisition of reinsurance company General Re had given Mr. Buffett a direct lesson in having to deal with the negative consequences of poorly written derivatives contracts [2].

In the letter, he references both of these experiences when he describes the critical underlying issues posed by derivatives:

The Principal–Agent Problem — situations where an Agent is empowered to make decisions on behalf of another person or set of persons, the Principal(s), and has difference set of incentives.

Mark-to-Market Valuation Issue — derivatives can be very difficult to value because there is a lot of judgment that goes into the calculation. The longer the contract term, the bigger the issue, as simple assumption changes can result in significant changes in the ultimate valuation.

Collateral Risk — derivatives are often structured where additional collateral is required if the bet moves against you. In other words, you may have made the right long-term bet but short-term volatility can force you to close out the bet at a loss before you have a chance to prove that you are right. As John Maynard Keynes once (may have) quipped, “the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent”. In other words, you need to be be right on both the bet itself as well as the timing of the bet.

Counter-Party Risk — with derivatives, not only do you have to evaluate the specific bet that you are making, you also have to consider the risk of the entity “paying up” if losses get really big. During the Global Financial Crisis, there was a non-zero chance that many of the prescient bets made by folks like Michael Burry and Steve Eisman never actually paid off because their counter-parties came that close to going bust.

“Daisy Chain” Macro Risk — increased systemic risk that is created when risk is passed down from party to party in a long complicated chain. Oftentimes, the risk can be concentrated in the hands of a few derivatives dealers, creating structural instability when things go wrong.

“The Smartest Guys in the Room”

By taking a deeper look at Enron, we can see how derivatives and the issues that arose by leaning on them had played a role in the rise and eventual collapse of the company:

Major Principal-Agent issues as senior executives — through large stock option grants — were financially incentivized to “juice” the stock price.

Shareholders held almost all of the downside risk, but senior management stood to make hundreds of millions of dollars if the stock price stayed high.

Management used Mark-to-Market accounting of derivative contracts that they entered into to manipulate earnings to create the illusion of growth despite major operational issues that were going on under the surface.

Liabilities were surreptitiously transferred to off-balance sheet entities structured by the CFO Andrew Fastow that were designed to be difficult to understand by the accountants (who were also financially incentivized to look away) and outsiders. Enron shareholders were still responsible for these liabilities, they just didn’t know it.

Enron ultimately went bankrupt when its counter-parties lost confidence in it and forced it to come up with cash collateral — cash that Enron didn’t have.

And while the Enron bankruptcy did not lead to broader systemic issues, seven years later derivatives contributed to the near-collapse of the global economy. In the film The Big Short, Dr. Richard Thaler and Selena Gomez provide an excellent explanation of what Mr. Buffett is referring to with “Daisy Chain” risk and how it could lead to macro blow-ups.

“Do as I say, not as I do”?

Despite everything he said about derivatives in 2003, Mr. Buffett personally structured around ten billion dollars worth of derivatives in the mid-2000s for Berkshire Hathaway. After again lambasting derivatives and how they contributed to the unfolding Global Financial Crisis in the 2008 Shareholder Letter, Mr. Buffett goes on to write:

Considering the ruin I’ve pictured, you may wonder why Berkshire is a party to 251 derivatives contracts (other than those used for operational purposes at MidAmerican and the few left over at Gen Re).

He goes on to describe how these derivatives fell into four categories:

Long-term equity put options on certain major market indices. For example, Berkshire Hathaway may have sold a “$1 billion 15-year put contract on the S&P 500” with a strike price of “say 1,300”. This means that if in 2022 the S&P 500 is 10% below 1,300, Berkshire Hathaway might have to pay out $100 million.

Credit default swaps on various high-yield bond indices. The standard contract here was a “five-year contract [involving] 100 companies”. These swaps would pay out if and when companies that were covered went bankrupt.

Credit default swaps on individual companies. Similar to the above except for individual companies vs. an entire index.

Tax-exempt bond insurance contracts that are structured as derivatives.

Wow. The standard-bearer railing against the evils of derivatives has just explained how he just went ahead anyway and entered into billions of dollars worth of derivatives.

What. A. Hypocrite.

“Kids, don’t try this at home”

Or was he?

In the letter, Mr. Buffett goes on to explain exactly why he entered into these derivative contracts in the first place:

The answer is simple: I believe each contract we own was mispriced at inception, sometimes dramatically so. I both initiated these positions and monitor them, a set of responsibilities consistent with my belief that the CEO of any large financial organization must be the Chief Risk Officer as well. If we lose money on our derivatives, it will be my fault.

And if you look more closely at these derivatives you will see how the situation is completely different from AIG or Enron and why the manner in which Mr. Buffett went about structuring these derivatives does not clash at all with the principled points he wrote years earlier:

First, there is no Principal-Agent issue here. Mr. Buffett was very clear in pointing out that he (as the “Chief Risk Officer”) is the one making these calculated risks. As the largest shareholder in Berkshire Hathaway, he has the most on the line if these risks go sour — both financially and reputation-wise. Contrast this with AIG executives who stood to gain tens of millions in bonuses while subjecting the corporation to risk measured in the tens of billions.

Second, Berkshire Hathaway took very little collateral risk. Berkshire was the one collecting the premiums on an up-front basis and in most cases, was not subject to collateral posting requirements. In the few cases where they agreed to post collateral, the maximum amounts were de minimis compared to Berkshire Hathaway’s balance sheet. Moreover, the long-term equity put options were European style meaning that they could only be exercised by the counter-party at the end of the contract — in other words, they could not force Berkshire Hathaway to settle the contracts in the middle of the contract.

Third, with the exception of certain credit default swaps written for individual companies — with premiums collected over the duration of the contract instead of up front — Berkshire Hathaway was not taking on any counter-party risk.

Fourth, mark-to-market valuation was not an issue. Mr. Buffett took great pains to explain the complicated process by which these derivatives were valued quarter-to-quarter only to advise shareholders to not even pay attention to the accounting on a short-term basis. He was certainly not looking to game earnings with derivatives — he has been very consistent for the last five decades about how to value Berkshire Hathaway.

At the end of the day, these derivatives were calculated bets made by a very shrewd investor on behalf of a corporation (and its shareholders) with the balance sheet to make these bets. He entered into them because he thought that more likely than not, they would pay off.

And if they did not pay off, they would never pose any sort of existential risk to Berkshire Hathaway itself. For example, in the very extreme scenario where Berkshire Hathaway is forced to pay $37.1 billion, the maximum loss on the equity put contracts, it will hurt but is still manageable (the company had around $121 billion of book value at the end of 2007 and this number would very likely be significantly higher in 2019 when the first option contract came due).

Of course, if Berkshire Hathaway had to pay the maximum loss, it would mean that stock markets have gone to zero and we are probably dealing with something more serious than having to worry about the solvency of Berkshire Hathaway. Like zombies.

What had actually transpired and precipitated Mr. Buffett’s involvement with derivatives was that other companies approached the company with very specific needs knowing that Berkshire Hathaway was one of the only companies out there (e.g. Triple-A credit rating) that could help them. They were structured to be very similar in nature to contracts written in Berkshire Hathaway’s core insurance operations — where premiums are collected up front to be invested over a long period of time. These contracts absolutely fell within Berkshire Hathaway’s “circle of competence”.

Warren Buffett wasn’t being a hypocrite … he was just trying to make some more money for Berkshire Hathaway shareholders … and derivatives are more of a “kids don’t try this at home” type situation.

Epilogue a.k.a. “Don’t expect to win a bet against Warren Buffett”

Sitting here in early 2018, we can see how these contracts have performed over time with the benefit of a decade’s worth of hindsight. Not surprisingly, Mr. Buffett has won many of these bets for Berkshire Hathaway and its shareholders … and ultimately society-at-large as he has pledged to is donate his entire stake to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

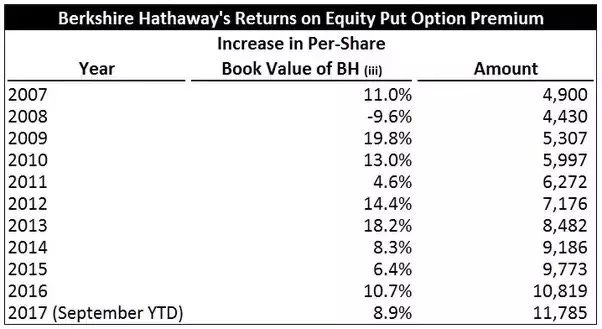

Let’s look at the long-term equity put option contracts which were written in 2007 near the top of the last bull market — not exactly great timing! For these contracts, Berkshire Hathaway collected $4.9 billion in up-front premiums. The maximum loss (if stock market indices went to zero) on these contracts was $37.1 billion.

When markets tanked around the world during the Global Financial Crisis, Berkshire Hathaway had to recognize accounting losses measured in the billions. But today, with equity markets more than recovering to all-time highs, Berkshire Hathaway’s liability is quite low if non-existent. Some contracts are already close to expiring. Meanwhile, Berkshire Hathaway has been able to invest the original $5 billion in market premiums. Assuming the same blended return as the rest of the business, these original premiums would have grown to around $12 billion by the end of 2017 [3].

That’s $12 billion in book value that would not exist if Berkshire Hathaway had not entered into these contracts. Not bad for what could very well have been a day’s work back in 2007!

Notes

[1] Okay, this is not technically true. In the past, Berkshire Hathaway has purchased options at its subsidiary MidAmerican Energy for “operational purposes” — my guess is for hedging fuel supply costs for certain power supply contracts. Also it inherited long-term derivatives from its 1998 acquisition of General Re.

[2] General Re was a large reinsurance company that had a derivatives operation that caused some major problems. These problems were eventually dealt with, but it was long, expensive and reputation-damaging exercise that Mr. Buffett did not want to have to go through ever again.

[3] Berkshire Hathaway received $4.9 billion in up-front premiums in 2007. This cash could be invested anywhere throughout the conglomerate. Based on Berkshire Hathaway’s growth in book value per-share since 2007, these premiums would grown to close to $12 billion by the end of 2017:

This was originally published on Quora in January 2018.