Why is counterfeiting so pervasive in China?

Perspectives from the front lines

From 2010 to 2014, I served on the board of a public company [1] that helped brands and governments fight counterfeiting using a combination of physical authentication, software and services. My private equity fund had invested in this company and we spent a lot of time with management thinking about China given how large its market is and how critical it is in the world’s manufacturing supply chain.

People often try to come up with cultural or social explanations to explain the pervasiveness of counterfeiting in China. While I would not go so far as to say these do not matter at all, I do think they are a lot less significant than people think and in any case virtually impossible to measure with any degree of accuracy.

In my view, it really just comes down to China being in the middle stages of development and having all of the characteristics that go along with being a developing economy, including:

A less educated, less affluent population

Weak and immature institutions

Different priorities between brands and regulators

The one factor though that is specific to China compared to other developing countries is that China has become the world’s manufacturing hub for almost every consumer (i.e. branded) good imaginable. This makes it really easy to source any amount of high-quality counterfeits at low cost.

As China gets closer and closer to being an advanced economy, we should see the size of its counterfeit economy shrink relative to the overall economy. The rise of domestic Chinese brands and advancements in anti-counterfeiting technology will help this along. In fact, I would not at all be surprised if at some point in the next decade Chinese companies themselves begin to take the lead in developing anti-counterfeiting technologies and measures.

(1) Social Proof

The temptation to counterfeit is omnipresent and comes from both the supply and demand side. I’ll tackle the demand side first.

Why do consumer purchase counterfeit goods in the first place? Let’s take bootleg DVDs as a simple example.

The first and most obvious reason is because consumers cannot afford the real thing or want to save money. Back in the 2000s it could take the equivalent of several days’ wages for an average Chinese person to purchase a single Disney movie on DVD at the full international price [2]. At the time (and even in many cases today), Chinese people simply could not afford imported intellectual property (i.e. media, software etc.) at international price levels.

The second reason is that Chinese consumers did not see anything wrong with counterfeiting. There was little stigma attached to watching pirated movies or wearing knock-off brands. And when certain behavior or attitudes get ingrained in society, it can be self-reinforcing — read what Charlie Munger has to say about how “social proof” can lead to fairly intractable “bad” behavior.

In developing countries like China, there are a lot of poor and less-educated people. They were either unaware, didn’t care or didn’t have the money to pay for authentic goods. This behavior eventually became the norm.

On the supply side, you find similar behavior. Consumer demand will inevitably be met by entrepreneurial counterfeiters. In the best-case scenario they do it openly — consumers know they are buying counterfeit goods and are okay with it. In worst-case scenarios, they do it by purposely trying to deceive consumers or secretly infiltrating the supply chain. It’s one thing to meet the demand of consumers who are okay with purchasing counterfeits; it’s something altogether different to deceive them particularly for the type of goods that can harm or even kill.

But in my view this “bad” behavior is merely a phase that developing countries go through and if you looked at Taiwan or South Korea in the 80s and 90s, you saw the same activity on a smaller scale. As I will delve into below, when developing countries become developed countries, consumers can also change often driven once again by the power of “social proof”.

(2) The Milk Powder Scandal

On July 16, 2008, sixteen babies in Gansu province were diagnosed with kidney stones. The babies had been fed formula produced by the Sanlu Group based in Shijiazhuang and it was discovered that the food products had been adulterated with melamine, a chemical that gives the appearance of higher protein content when added to milk. Presumably this had been done for cost-saving reasons.

After authorities investigated it was revealed that this was a more widespread industry issue that included almost two dozen other companies (there’s the “social proof” concept at work again). Of an estimated 300,000 victims in China, six babies died from kidney stones and another 54,000 were hospitalized.

This was one of the largest food-safety scandals in recent history and it ultimately led to criminal prosecutions including two executions.

Buying bootleg DVDs is one thing. Selling harmful food products to babies is on a completely different level. But is this a reflection of Chinese culture and society? Do Chinese people fundamentally love their babies less than others? And where were the authorities in all of this?

I would argue that it is more a reflection of where China is in its stage of development. The reality is that up until this point, China’s institutions had to deal with much more basic issues than milk powder safety … like making sure people actually had enough food to eat in the first place. Poor mothers don’t buy milk powder for their babies — they breast feed. Authorities did not have to deal with tainted milk powder before because until now it had never been “a thing”.

But as China’s middle class got big and as busy urban mothers began to look to alternatives like milk powder, it became “a thing”. And companies looked to meet this demand. Cut-throat competition (very common in China) led to corner-cutting and cutting corners became widespread, almost a competitive necessity. Then the inevitable scandal breaks out. It is investigated, people are executed / go to jail and authorities come up with new rules and processes to try to make sure this situation doesn’t happen in the future.

That is how development works. You cannot create rules and processes to cover every anticipated situation. And as China develops, it is constantly facing new situations and its regulations need to be constantly updated. Not to diminish the suffering of those involved in the milk powder scandal, but setbacks like this are a necessary part of development. And there will unfortunately be many more of these type of incidents as China continues to develop in the future.

Anybody who has ever read Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle will appreciate this and understand that this phenomenon was not a China-only thing.

(3a) Different Priorities …

Working with OpSec Security, I learned that there are many different “levels” of counterfeiting and I learned how regulators and brands differed in their approach to anti-counterfeiting measures. One framework categorized different types of counterfeiting along two vectors:

Consumer awareness:

Does the customer know that they are purchasing a counterfeit good?

Severity of impact:

Regulator perspective: How much harm can be caused by using counterfeit product?

Brand perspective: What are the economic costs (direct and indirect) caused by the proliferation of counterfeit product — measured against the often non-trivial costs of policing it?

Generally, the farther to the top-right corner of the table, the more incentive there is for regulators and brands to fight counterfeiters. Regulators would of course care about anything that could kill or harm consumers. Brands would care about the economic harm caused to the brand, whether it was through lost sales or brand damage.

And generally regulators and brands cared much less (if at all) about the types of counterfeits at the bottom-left corner i.e. customers that knowingly purchase counterfeit goods, particularly low-quality knock-offs. They might make a big deal about some huge theoretical loss number but deep down they know these were never true customers anyway.

The middle of the chart is where things get a bit murkier. Higher-quality counterfeits could cause significant economic harm to brands because they might be stealing a potential customer that may have otherwise purchased the more expensive authentic good.

Brands are usually most concerned about the bottom-right corner. First, regulators tend to not focus as much here, especially in China where high-value consumer brands are usually foreign. Most significantly, this quadrant is where the most potential economic harm occurs — i.e. mass affluent type goods with big aggregate dollars involved. A prime example of this was sports licensing.

(3b) … Different Solutions

Sports licensors (think MLB, NBA, NFL) ranked among the largest customers for the anti-counterfeiting company I was involved in.

Licensing has become a major revenue generator for the sports leagues, ranking third after media/television rights and ticket sales in overall contribution. As licensing started to gain traction several decades ago, the sports leagues immediately found themselves having to deal with the counterfeiting problem.

Unlike clothing manufacturers which have operating expertise, sports leagues had no prior operating knowledge when they started to license. So they outsourced heavily to third-party manufacturers, most of whom were based in Asia.

There is a joke in the industry that the first box of went out the front door and the second box went out the back.

The sports leagues quickly realized that the biggest counterfeiters were their own factories. And this was really harmful because they were manufacturing counterfeits that were exactly the same as the real thing. On top of that simple tracking and collecting of revenue was difficult. Consumers were either being fooled or they were ecstatic to pay less for what was essentially the same good.

Suing the factories was pretty much useless. China’s legal system was woefully undeveloped — it did not even enact modern Tort Law until 2010. Switching factories might work for a bit but it was a pain and soon the new partners would find how temptingly profitable it was to do a little counterfeiting on the side.

So how did the sports leagues ultimately address this issue? It turns out a simple holographic label did the trick. Here is one on my favorite Brooklyn Nets cap:

These labels were inexpensive to produce and very difficult to replicate perfectly. For the same reason that holograms were used on credit cards, consumers came to recognize these labels as a mark of authenticity. The sports leagues could now just ship a batch of labels to its licensed factories and charge them on a per-label basis. The factories could still ship stuff out the back door, but that product would not come with a label marking its authenticity.

When they did ship stuff out the back door, it was much easier to track the goods through the supply chain. Licensors use field agents that go around the world doing spot checks at various retail outlets to see if their product is authentic. When they spot problems, they can gather evidence that can trace the counterfeiting problem to the source. If they find out that it is their own factory shipping product into the "gray market", they can confront them with evidence and give them a very easy choice — stop this behavior or we will switch to your competitor. Usually the factories choose the former.

Today, counterfeiting is still an issue for sports leagues but it is less their own factories cheating them and more an issue with lower-quality knock-offs proliferating the market. But they are less concerned with this type of counterfeiting because the clientele for lower-quality counterfeits were probably never going to purchase authentic goods in the first place.

The Future of Anti-Counterfeiting

I remember being very surprised when I found out that the customer with the most sophisticated (from a holography perspective) anti-counterfeiting needs was a Chinese cigarette manufacturer.

Many people outside China think that it does not have many valuable consumer brands. Part of the issue is again where China sits on the economic development curve — it has not quite reached the point where foreigners and even locals put a whole lot of value on domestic Chinese brands (although we appear to be hitting an inflection point). The other issue is that up to now, many of China’s most valuable brands only catered to Chinese people [3].

For example, one of them is baijiu (白酒). Normal bottles of Moutai baijiu can go for thousands of yuan and vintage bottles have been sold for over a million. Kweichow Moutai is among the most valuable liquor companies in the world.

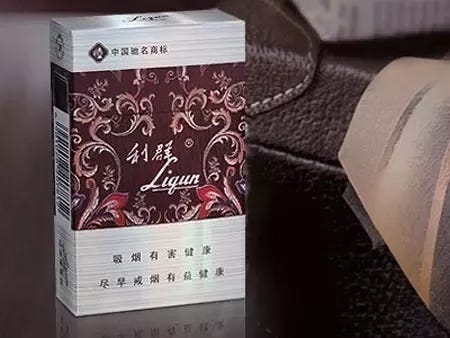

Another is luxury cigarettes like Liqun (利群) brand. Cartons of the luxury versions of these cigarettes can go for 1,900 RMB per carton. Both luxury alcohol and cigarettes were the de facto choice for “gift giving” before Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption crackdown.

Both of these Chinese-branded alcohol and tobacco products are heavily counterfeited in China. And both have had to learn how to utilize various anti-counterfeiting measures to combat counterfeiters.

In the case of cigarettes, just like with licensing, holograms play a significant role in the fight against counterfeiters. And in the case of cigarettes, the hologram is on the box and has become an integral part of the brand. Due to very specific technical reasons that I won't get into here, these holograms had the most sophisticated requirements and were the most difficult to manufacture at high yields.

By the way, Liqun is part of China National Tobacco Corporation which has a virtual monopoly on the cigarette business in China. It is a state-owned enterprise so we are not exactly talking about the most entrepreneurial and innovative company here.

The reason I bring this up is because it was an indication to me that — when it matters to them — Chinese firms have proven that they will go to great lengths to combat counterfeiting. And as other Chinese brands start to rise in value and prominence in other industries — something I think we are on the cusp of today — they are going to start having to deal with the counterfeiting issue as well in a big way.

Meanwhile, consumer behavior is also changing as China's middle class expands and society is generally better off. Incidents like the milk scandal inform and educate society on the harmful effects of counterfeiting and cutting corners. Economic incentives change. “Social proof” starts to work its magic in the other direction as the stigma attached to counterfeit goods rises. Consumers increasingly demand and are willing to pay a premium for authentic goods.

Indeed, when I left the board of the anti-counterfeiting company in mid-2014, we were already starting to see Chinese entrepreneurs tackle this problem head on and coming up with new and innovative way of combating the counterfeiting problem. Given the size of China's market, the scale of the counterfeiting issue and the changing behavior of consumers, I think it is quite likely that China will start to play a leading role in the anti-counterfeiting industry in the coming years.

Related

Notes

[1] OpSec Security Group. The company was subsequently taken fully private and de-listed in October 2015.

[2] Average hourly compensation for a Chinese manufacturing worker in 2002: 60 cents per hour. Movie DVDs cost anywhere from $15 to $30 back in those days. This is equivalent to 2.5 to 5 days of 10 hour per day labor and does not factor in taxes and other daily expenses.

[3] 2012 Top 50 Chinese Brands. If we exclude domestic services companies, you will find that the top Chinese brands five to ten years ago were in the alcohol and tobacco category.

This was originally published on Quora in January 2018.