Why is China wealthier than Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines?

Tapping into entrepreneurial energy

It all comes down to figuring out how to tap into the entrepreneurial energy of a nation and directing it in ways that are beneficial not just to the entrepreneurs themselves, but to the rest of society as well.

In China, for the most part entrepreneurial energy is directed at activities that benefit the broad population e.g export businesses that create jobs that can provide a life of dignity for millions. Thailand is actually doing okay too.

However, in Indonesia and especially in the Philippines, a lot of entrepreneurial energy goes into zero-sum activities like rent-seeking and political patronage.

Why certain countries figured it out while others did not can be to a large extent explained by a surprisingly common thread that many today do not really appreciate: Land Reform.

The Importance of Land Reform

Similar to how land reform played a positive role in the early development of Taiwan and South Korea, agricultural and market reforms in China in the early 1980s (building on earlier land reforms) kickstarted its economic reforms. In contrast, lack of serious land reform led to slower development (in varying degrees) in Thailand, Indonesia and (especially) the Philippines.

Land reform was hugely important for these poor Asian countries because all of them featured large populations and a relative scarce amount of land.

Compare this to most developed Western countries, where land is relatively abundant while it is labor that is scarce/expensive [1]. This means that agricultural development strategies – large plot sizes, liberal employment of technology/capital and generally less labor-intensive approaches — that work well in countries like America, are not necessarily a good fit for Asian countries.

Still — and frankly not surprising at all — this was the approach the European colonialists took with the Philippines and Indonesia [2], setting up large “plantation style” farming enclaves often managed by a local boss. As you might guess, most of the best land was owned and controlled by the European masters as these colonies were viewed mainly as resources to be exploited as rapidly as possible.

When these countries gained their independence, these local bosses very naturally assumed control of the plantations in place of their erstwhile European masters. Of course, these local bosses quickly grew to prefer the “plantation” style farming because that meant that they were the ones that owned and controlled the land. For very poor countries, almost all of its capital stock is tied up in its stock of arable land.

As a result the vast majority of people ended up continuing (just like they had in colonial days) to work on these farms as laborers. Under such a system, there was really very little chance for them to save money and accumulate capital — they were destined to be laborers for the rest of their lives. Even more significantly, productivity remained stubbornly low because the incentives were just not there for these laborers to work hard or get creative and figure out ways to become more productive.

Not that the governments in these countries did not try to implement land reform programs. But the problem was that these “local bosses” (who were rapidly accumulating wealth and turning into “Asian Tycoons” and oligarchs) held a significant amount of economic power and many of them used this to influence the politicians and the government – such as by halting or minimizing land reform programs. The best measure of how well land reforms did is by looking at the ratio between landed farms and non-landed laborers. These percentages simply did not improve much in the Philippines and Indonesia, despite repeated attempts at land reform.

In China, one of the good things that the Communists did in the early 1950s was to implement a massive land reform program, distributing land that had previously been concentrated with a small group of landowners to the villagers [3].

However, the positives of these land reforms were all but nullified by other policy disasters like the Great Leap Forward. And because this was the peak of Communist Red China, there were no market mechanisms in place to provide farmers with the incentive they needed to work hard. Agricultural productivity improved at first, but later stagnated and even declined in later years. It wasn’t until market reforms were introduced in the late 1970s and early 1980s by Deng Xiaoping that the positive benefits of land reforms done three decades ago began to bear real fruit. It was not a coincidence these first market reforms took place in the agricultural sector.

An even better example of the power of land reform was Taiwan. Like the Communists in China, the KMT also believed in land reform and they implemented major land reforms in the 1950s, which led to a more than doubling [4] in the number of farmers that owned land. Taiwan’s agricultural productivity soared in the 1950s and 1960s, turning it from a net food importer to an exporter and allowing it to starting accumulating hard capital that it would use during its next phase of industrialization.

Hammering home the point that incentives really matter, its labor-intensive approach with highly incentivized “farmer-entrepreneurs” was able to produce far higher yields per acre than plantation-style farming in all of the Southeast Asian countries. This is despite the fact that Southeast Asia has some of the most fertile farmland in the world [5].

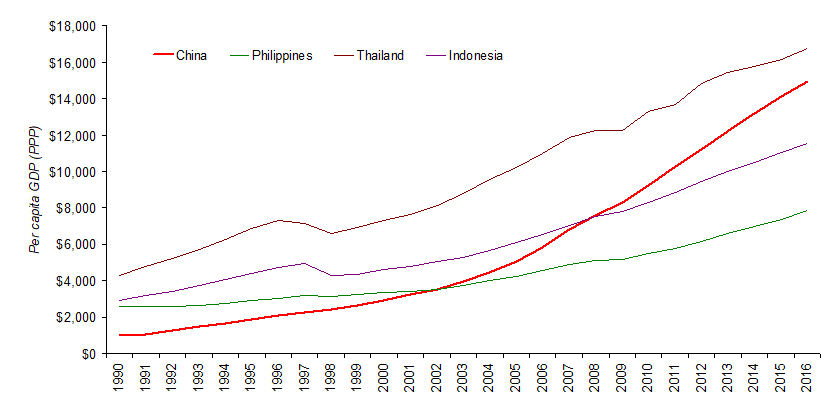

To be clear, China did not “do land reform” as well as Taiwan. Moreover, policy blunders and a rigid adherence to Communism held mainland China back for three decades. But it “do it” better than these three countries and once market forces were unleashed, the Chinese economy leapt forward. Starting in a very distant last place, China sustained double-digit growth rates for three decades. It passed the Philippines in 2002, Indonesia in 2008 and is likely to pass Thailand by 2020.

Land reform policies also impacted the industrialization path that was chosen ...

The benefits of successful land reform did not just stop at simply higher agricultural productivity. Because capital was spread more evenly throughout the population, opportunity was also more equally spread out. For example, most farmers in Taiwan got a small plot — and some of them figured out very early that their skills might be best utilized elsewhere. They were able to sell off their land, netting them a small amount of capital and with this capital, they could perhaps start a small factory making toys or something. Moroever, the government encouraged these types of businesses to export out to the world, which helped the country find jobs for and tap into this inexpensive labor streaming out of the countryside into the cities. Many of these business entrepreneurs are fabulously wealthy today but more importantly, they have created millions of jobs for the population and helped their nations move up the value chain. Like Taiwan, China also made exports a key part of its industrialization strategy. Moreover, China had the benefit of experience of Hong Kong and Taiwanese exporters that had laid a lot of the groundwork to establish export businesses.

Opportunity was not as readily available in the Philippines and Indonesia because after a couple more decades of wealth accumulation, the entrepreneur-tycoons had lots of capital and were figuring out new ways to deploy it. Moreover, the most successful tycoons were generally the ones that knew how to work the best with politicians and government officials. So it is natural that as the countries moved to the industrialization phase, the most capable tycoons used the same blueprint. Instead of building export businesses where you had to compete on merit, the natural inclination is to build a protected domestic business, actively engaged in what economists call “rent-seeking”. This wasn’t true industrialization or manufacturing — in many cases, these protected businesses merely imported close-to-final products, merely adding a thin layer of light final assembly. Their profit margins were primarily driven by the moat created by an artificial government-sanctioned license/monopoly. Many tycoons became even wealthier, but by engaging in activities that did not have many positive spillover benefits for the masses.

The problem with the Philippines and Indonesia (and to a much lesser extent, Thailand) today is not that the masses lack desire and energy to be entrepreneurial and work hard. Just look at the hard-working domestic workers from these countries that leave their children and families to go off to an alien place where they are treated like second-class citizens just so they can earn enough money for their families just to survive. The issue is that wealth inequality has metastasized to the point where the ones with economic power also have political power and if anything, their incentive is to stifle entrepreneurs from encroaching on their protected income streams. Society tends to moves forward at a lurching pace under these conditions and that’s exactly what has happened.

Addendum

I want to end on a positive note so I wanted to add a couple more points:

That they didn’t “do land reform” that well doesn’t doom these countries economic purgatory. It does mean that it will take more time however, because there are more obstacles to overcome. With more time, I do believe that their citizens will figure out how to leverage market forces and new technologies to the institutional challenges presented by wealth inequality.

In fact, these countries have prospered in recent years. The Philippines’ BPO/call center industry recently topped India’s to be the world’s #1. Indonesia is a thriving democracy and its young consumer population is driving robust growth. Thailand is one of the most exciting social media market for Facebook.

I do not necessarily blame the “Entrepreneurs cum Oligarch Tycoons” in these countries. They were the product of a broken system and just doing what smart, motivated entrepreneurs do everywhere which is to “get theirs”. The blame lies almost entirely on the system itself. Fix the system to make sure they are directing their entrepreneurial energy the right way, and everyone can benefit and prosper.

Notes

[1] This is a major reason why America, where this scarce labor / abundant land ratio is one of the most skewed, is home to the world’s leading agricultural technology (capital equipment as well as agricultural biotechnology). Most Americans don’t realize this (because most of us live in suburbs and cities), but the agriculture and agricultural technology sector rank as one of America’s most significant comparative advantages.

[2] Thailand was not colonized, which is probably why it has done better in this area. Still, while it implemented its land reform programs better than the Philippines and Indonesia, it was still far less successful than China, South Korea and (especially) Taiwan.

[3] I have a bit of family experience with this – both the paternal and maternal sides of my family lost their land.

[4] From 30% in 1945 to 64% by 1960. Source: How Asia Works by Joe Studwell (page 31). Mandatory reading for this topic.

[5] Taiwan’s isn’t bad either but they were also being beat by South Korea, whose farmland is nowhere near as productive.

This was originally published in Quora in February 2016.