Why are high-speed train tickets in China so cheap?

Minimize cost and maximize utilization

For the average Chinese person, high-speed rail (HSR) tickets aren’t necessarily “cheap” at this point in time. While not entirely unaffordable, travelling on high-speed rail is a luxury for the majority of Chinese people, especially the roughly two-fifths that live in the countryside.

Of course, I would note that leisure travel itself is a luxury for poor people … and there are still a lot of poor people in China. For middle class urban families, high-speed rail is a relatively economical and civilized way to travel compared to the alternatives.

Also, since these are ultra-long-lived assets, one cannot solely focus on the first four or five years of the project. What matters is whether it delivers value over the next hundred years. And it is increasingly clear that China’s new high-speed rail network will deliver significant long-term benefits to the development of society and the economy.

There are three key factors that drive the long-term economics of high-speed rail and influence how ticket prices are set:

Up-front build cost (mostly fixed)

Operating costs (mostly variable)

Utilization

High-speed rail ticket prices will be set based on the recovery of fixed costs, variable costs and some sort of profit or return on capital expectation.

To minimize ticket prices, the strategy is very straightforward from a mathematical perspective:

Minimize the up-front build cost

Minimize variable costs

Maximize utilization

I’ll take each of these points in turn below and describe how they apply to China’s HSR network buildout.

(1) Minimizing fixed costs

Typically, the largest cost item in a high-speed rail project is the fixed upfront cost of building out the rail network. This includes major categories such as:

Land acquisition and resettlement

Civil works

Track

Signaling and communications

Electrification

Rolling stock

Buildings including stations

Other costs including capitalized interest

Once built, these items are classified as long-lived assets: railway companies are typically capital-intensive businesses that feature big balance sheets dominated by the “plant, property and equipment” category. These long-term assets need to be financed, typically by a combination of debt and equity.

The way that very long-lived assets are accounted for on the income statement (and ultimately in the calculation of ticket prices) is via:

Cost of capital

Depreciation

Both cost of capital and depreciation are calculated as a percentage of that up-front fixed cost. So the more you can minimize these percentages and/or the up-front fixed cost — ideally, both — the more effective you will be at keeping ticket prices affordable while still maintain a degree of profitability and return on capital to debt and equity holders.

It turns out Chinese HSR planners did a pretty good job on both fronts.

China’s cost of capital is relatively low. This was largely the result of some key economic and financial policy objectives:

Macro-economic stability

Relatively low inflation

High savings rate that can be funneled into investments

State-controlled banking sector that plays a critical role in allocating capital

China also managed to hold down the cost of building its high-speed rail networks with build costs of between $17–21 million per km compared to $25–39 million in several E.U. countries. This was the result of several key factors:

Scale and its impact on construction productivity

Scale and its impact on technology acquisition — leverage to negotiate technology transfer and support the build out of indigenous industry for many key areas in the rail value chain.

The State’s ability to minimize land acquisition and resettlement costs and reduce project build time.

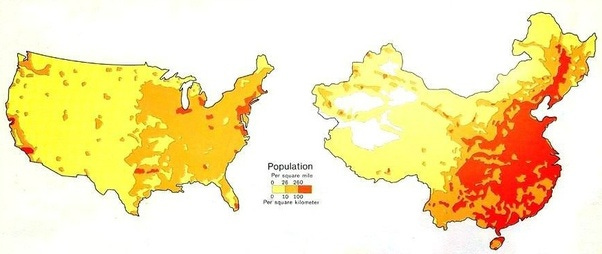

Somewhat favorable topography — reducing the need for expensive bridges and tunnels — as the vast majority of China’s population lives in relatively flat areas. You can see this by super-imposing a population density map on top of a physical map.

Relatively inexpensive labor cost

(2) Minimizing operating costs

Once a train network is built, the key operating items are:

Labor costs (running the trains, maintaining the assets, managing the entire operation)

Electricity and energy costs

Material costs to repair trains and track and maintain operating facilities like train stations, train depots, and electrical and signaling equipment

In aggregate, the largest cost in running a network are labor costs. To the extent labor costs are low, operating costs will also be low.

Of course, labor cost is highly correlated with income and affordability. As China’s labor costs rise, incomes should also rise so these effects largely cancel each other out. “Cheap” is a relative concept.

(3) Maximize utilization

The most important long-term factor driving railway economics is utilization. With train networks, the marginal cost of carrying another passenger on a train, or running another train on the same line is relatively low compared to the fixed cost of building that line.

As such, the more a rail network is utilized, the more you can amortize the high fixed costs associated with the up-front costs of building out the rail network across a larger pool of usage.

For example, by doubling usage of a network, you would effectively halve the fixed charge per passenger-km.

In addition, there are other indirect benefits to heavy utilization. For example, Chinese train stations are among the heaviest trafficked places on the planet. This traffic can be (and is) monetized by leasing out the real estate at relatively high retail lease rates or by selling advertising. Indeed, China Railway Corporation — the state-owned enterprise that owns the entire HSR operation — is profitable no doubt in large part due to its ability to monetize the traffic that its passenger rail network generates.

There are several reasons why China’s utilization is so high:

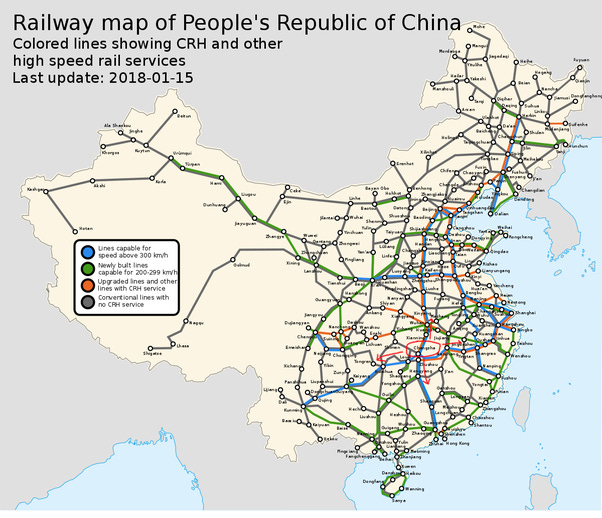

Higher population density (particularly in the eastern half) which drives higher demand for inter-city transportation.

The “web-like” pattern of Chinese city placement. Web-like rail networks drive higher utilization than point-to-point networks because there is a lot of interchange traffic. The city of Changsha (circled in red below) is a good example of this: It sits at the crossroads between several major regions and many passengers use the city to transit from one region to another.

HSR is less expensive than alternative transportation options for certain routes, especially when you factor in comfort. It is relatively more expensive to have your own car in China (taxes, parking costs). Bus transport is very inexpensive but slower for journeys longer than 200 km.

To summarize, here are some of the key themes:

(A) China enjoys many “natural,” structural factors that make the economics of high-speed rail attractive, especially compared to the United States:

High population density

Web-like pattern of city placement and urban development — less low-density suburban sprawl which makes land acquisition more difficult

Generally mild topography — reducing need for expensive tunnels and bridges

Slack labor capacity — soaking up labor in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis

(B) The heavy role of the State clearly is a recurring theme here across many areas:

Economic policy directives that result in lower cost of capital

Ability to “efficiently” requisition land along the straight paths needed by high-speed rail lines

Whatever your views may be on the heavy role the State plays in China’s economy, it is hard to argue against the idea that it played a critical role in the build-out of China’s high-speed rail network.

(C) China’s scale was a major factor here. Scale allowed China to make certain planning decisions that are not necessarily available to other countries:

Negotiating leverage to demand technology transfer agreements with other countries (again, whether or not one agrees with this practice is a different issue).

Standardized processes — best practices in design and site selection could be quickly propagated from one line to the next. This is why many train stations (outside of the Tier I cities) look and feel very similar, down to the design of intermodal links they have with local transport like buses and subways.

Improved productivity — scale allowed construction firms to come up with innovative new ways to increase construction productivity.

(D) The relationship between cost of labor and income is an interesting subject to ponder.

On the one hand, low labor costs are almost always correlated with low incomes. In other words, just because you can build it relatively inexpensively compared to other countries does not mean it is necessarily affordable for most people. Indeed, one of the criticisms of Chinese high-speed rail projects has been that they were unaffordable for the vast majority of Chinese people.

On the other hand, if you are confident that future incomes will rise significantly, to the point where what was once unaffordable is now affordable, then you can think about high-speed rail as an arbitrage between yesterday’s inexpensive labor situation and a rich, productive world of tomorrow. Yes, you could have waited a few years to start building high-speed rail but each year that you waited would increase the build cost commensurately. Even if ticket prices are relatively unaffordable for the first five years of the line, what really matters is whether they are affordable over the next hundred.

On a related note, as much as labor costs may rise in the future, the inevitable rise in Chinese NIMBY-ism could very well have an even greater effect on the cost of future HSR development.

(E) High-speed rail lines freed up capacity for commercial freight. Given the unique requirements of high-speed rail (very straight, level paths with ultra-wide turning radius), almost all lines were of the new build construction variety.

In other words, existing rail lines that had previously been used for passenger traffic could be used for additional freight capacity (commercial freight is less time-sensitive than passenger travel).

(F) The role that the relatively low cost of capital played in financing the build-out of China’s high-speed rail network also deserves some airtime.

Some have argued that without subsidies (including financing subsidies), the high-speed rail network would not make economic sense on its own. First, I am not sure this is even true. Second, even if it is true now, it could very well be because many of the lines are still relatively new and take time to ramp up. Third, is not even clear whether low cost of capital available to finance HSR is a function of a stable, well-run economy or direct subsidies.

But even beyond this, the argument that it’s not “right” to subsidize high-speed rail is suspect as well. It is obvious that high-speed rail delivers societal benefits beyond the financial returns to banks, bond and equity-holders.

These benefits include:

Environmental impact — reducing reliance on less energy-efficient modes of transportation like air travel and single-passenger vehicle transport.

Increased economic activity — by providing a more attractive transportation option, you stimulate economic interactions that may have been heretofore unavailable. Reducing the friction costs of business has benefits that compound over time. HSR is a key infrastructure element in enabling the development of a next-level of Chinese megalopolises, including ones that may ultimately house over 100 million people. These are something the world has never seen before and there could be interesting second-order effects that have not been heretofore contemplated.

Strategic benefit — China catalyzed the creation of new industry where it now has a fairly decisive comparative advantage. The knowledge and experience it gained building its own network can effectively be monetized to the economy’s benefit by selling its expertise to the rest of the world. We are seeing this play out heavily in its “One Belt, One Road” initiative.

With so many non-financial reasons to point to, there is actually quite a strong rationale for HSR development in China to be subsidized. One role of government is to encourage socially beneficial economic activity that might be hard for the private sector to handle. This would include projects that deliver sub-par financial returns — or take a very, very long time to deliver returns — but come attached with major spillover benefits to society.

This was originally publised on Quora in October 2018.