Where does the money I pay for an iPhone go?

A journey around the world chasing the money trail

Let me invite you on a journey around the world: From the high streets of London … to Zhengzhou, a booming Tier II/III city in China … to Apple’s corporate headquarters in sunny California … to the Emerald Isle … and finally back here to Lower Manhattan.

As we travel on this journey, I will try to explain how the money flows from that point-of-sale purchase to my brokerage account when the company pays out its quarterly dividend.

This journey is interesting because it helps shine a light onto the increasingly complex and globalized world in which we live.

(1) Retail — the Apple Store

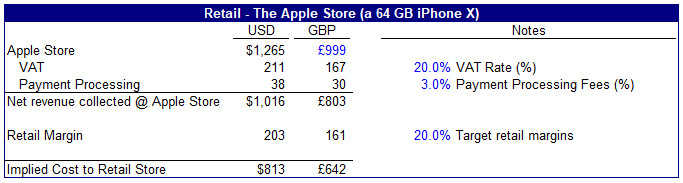

I walk into the Apple Store on picturesque Regent Street in London’s posh Mayfair district. 15 minutes later, I stroll out with a base-level 64 GB iPhone X for £999.

The money starts to flow as soon as I successfully input the PIN for my Barclaycard into the payment terminal:

The U.K. has a 20% value-added tax (similar to a sales tax in certain states in the U.S.) which means £167 comes right off the top to fund government and public expenditures.

Since the iPhone was purchased with a credit card, another 3% or so is taken out by the payment processing companies, leaving the retail operation with a net total of £803 collected. If I had paid with cash, there would be some indirect cash handling expense that the retail operation would absorb (probably higher than 3%).

For illustrative purposes, let’s say that Apple targets 20% retail margins to cover the costs of its beautifully designed Apple Stores. This means that the store is allocated about £161 per iPhone to pay for that expensive Regent Street rent, store employee salaries, Apple Geniuses, utilities, depreciation on the store’s capital improvements, etc.

This leaves £642 that ultimately flows to Apple’s UK entity.

(2) Manufacturing — A Globalized Supply Chain

Now we need to hop on a Cathay Pacific flight from London to Hong Kong with a quick layover before transferring to a Dragon Air flight to Zhengzhou, a city in China that is about the size of New York City’s five boroughs … that many of you have probably never heard of.

Don’t worry, though. These days even the locals simply refer to it as “iPhone City”.

Zhengzhou is the capital of the densely populated, relatively impoverished Henan Province whose industrial economy had historically been centered around light textiles and food processing. Situated at the transition between the North China plain and the Qinling mountains, it is about a 4–5 hour (around 900 km) high-speed train ride from Shanghai.

This is where Apple’s Taiwanese contract manufacturing partner Foxconn decided to locate its second major industrial operation after its main Shenzhen complex. With generous support from the local government, Foxconn spent hundreds of millions of dollars building out factory operations in an area that was specifically set up to export consumer electronics. For example, it is located in a “special bonded zone” that is legally considered foreign soil under Chinese regulation (doing it this way helps makes the logistics more efficient).

In August 2010, the first lines at Foxconn’s Zhengzhou factory began production. A little over eight years later, it produces around half of all of the iPhones in the world, churning out upwards of 500,000 per day.

Along with 350,000 employees who work at the factory (during peak times), tens of millions of components from all around the world and other regions in China stream into Foxconn’s Zhengzhou factory on a daily basis. Many of the semiconductor components are designed in one part of the world only to have their ECAD designs electronically transmitted to Taiwan’s chip foundries for fabrication.

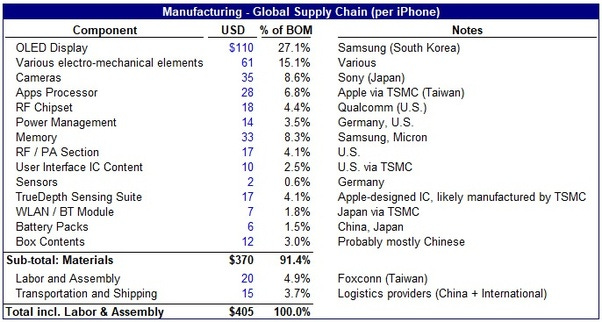

Here is a summary of how the bill of materials (BOM) breaks down:

My recently purchased base-level 64 GB iPhone uses an estimated $370 worth of materials and components. Adding in around $35 in assembly and logistics costs and we are looking at a total BOM cost of around $405.

The biggest cost item is the OLED display from Samsung, making up around 27% of the BOM. This is because Samsung is the dominant supplier of advanced OLED screen technology and is able to command premium prices. It is also why Apple is pushing so hard to foster greater competition in the industry.

Another notable component is the RF chipset supplied by Qualcomm. While a relatively modest 4% of the BOM, what is not included in the table above are additional 4G licensing fees that are paid separately by Apple. I’ll come back to this in the next section.

Many of the other discrete analog and digital semiconductor components primarily supplied by U.S., German and Japanese fabless semiconductor designers are often fabricated in chip foundries in Taiwan (e.g. TSMC).

Notably, China’s value-add to the BOM is relatively low and mainly comprised of more labor-intensive elements or less advanced components like the lithium-ion battery, packaging or simple accessories like the standard white Apple headphones. Overall I estimate China’s contribution to the BOM at around 13%.

Okay, we’ve spent enough time in the “iPhone City”. We now need to catch our Air China flight from Zhengzhou to San Francisco via Beijing. We are heading to Silicon Valley.

(3) Corporate — One Apple Park

This is where the magic happens.

Apple’s recently opened new headquarters occupy 2.8 million sf in Cupertino, in the heart of Silicon Valley. Built at a construction cost of around $5 billion, it houses 12,000 highly compensated employees.

It is here (well, technically nearby at the old Apple Campus) that the iPhone and other Apple products were conceived and designed. It is where corporate executives like Tim Cook make big decisions about the next versions of existing product lines, the next advertising campaign, or how the company should allocate the product development dollars.

And this is where — at this very moment in late 2018 — executives are likely debating whether it makes strategic and financial sense to diversify Apple’s manufacturing base outside of China by setting up another “iPhone City” in places like Vietnam.

These corporate expenses are primarily fixed costs that you can amortize across the entire global revenue base of the company. As an example, in FY2018, Apple’s R&D expenses totaled $14.2 billion, or 5.4% of revenue. If we break it down on a per-unit basis, this comes out to something like $41 per iPhone sold [see Note i]:

Between the £642 ($813) that flows into Apple’s UK corporate entity and the $405 BOM, you have $407 that flows back to Apple Inc. This money will be used to pay for:

Corporate costs including sales and marketing, product development and general and administrative costs

These costs are mostly comprised of employee compensation, whether in the form of salary, bonus or stock-based compensation.

Rent for all of the leased office space around the world; maintenance and depreciation for its owned properties.

Spending is heavily concentrated in Cupertino/California although Austin, Texas is rapidly turning into Apple’s version of “HQ2”.

Apple also spends heavily on brand advertising.

Global licensing fees / Qualcomm

As I alluded to above, Qualcomm is entitled to collect royalties on any device that connects to a 3G or 4G network (which includes basically all smartphones).

This is because of patents and intellectual property that it created (and acquired) over the years, primarily around a “channel access method” called code-division multiple access (CDMA) on which almost all modern wireless standards are based today.

Moreover, the licensing agreements that it negotiated many years ago stipulate that it collects a percentage of the entire “final sale” price of the smartphone — so as these devices have gotten more complicated (and more expensive) over time, Qualcomm has collected more revenue.

As you might imagine, this is causing a lot of friction along a number of fronts — many companies are questioning why Qualcomm should collect the same percentage (or any percentage at all) on peripheral components that have nothing to do with wireless.

This is one of the primary reasons why so many other companies are focused on building their own IP portfolios for the next generation of wireless standards (5G). This article from Macro Polo discusses the whole saga in detail and I would recommend reading it if you have time.

In any case, what this means for Apple is that it has to pay 3.5% of the final sale price of the iPhone to Qualcomm (with “final sale price” capped at $400 to $500).

After paying off all of its corporate expenses and (reluctantly) cutting a massive check to Qualcomm, there is $281 left. This equates to 27% of the net revenue collected on Regent Street. Apple’s overall operating margin is 27% … so this passes the sanity check [see Note ii].

(4) The Tax Man

“We all know this deal is as certain as death and taxes.” — from Meet Joe Black, one of my all-time favorite movies.

Apple is enormously profitable. In its last fiscal year (FY2018: 12 months ending 9/30/2018), it generated $72 billion of earnings before taxes. That is $72 followed by 9 zeroes. And the Tax Man is salivating at the sight of all of that taxable income.

Historically, the U.S. corporate tax rate was 35%. Under the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the corporate rate was lowered to 21%. Including state-level corporate taxes, the average corporate tax rate is 26%. Apple is a U.S. company headquartered in California, so all we have to do is multiply the $72 billion by 26% and call it a day, right?

Wrong.

In FY2018, Apple provisioned $13.4 billion in corporate income taxes, which comes out to an 18% effective tax rate. That’s 8% lower than the prevailing rates. How is this possible?

The reason is that tax rates are different all around the world, so multi-national corporations (and their accountants) are always trying to figure out how to legally lower the amount of taxes they have to pay. For uber-profitable companies like Apple, the stakes are massive — each 1% reduction in your effective tax rate is $700 million of additional net income.

Technology companies are especially good at this, because much of what they are selling is “intangible” (i.e. software, intellectual property, etc.) and they also tend to sell globally which means the flexibility of multiple tax jurisdictions to play with. So even though the IP assets that Apple develops are mostly created in Cupertino and the United States, from a legal and tax perspective, the IP is actually located outside of the country.

This is why instead of flying to Washington, D.C. where the IRS’ headquarters are located, we are now boarding an Aer Lingus flight to Dublin, Ireland.

In the aftermath of World War II, while most of Western Europe boomed on the back of the Marshall Plan and post-war reconstruction, Ireland was held back by its “economic nationalism” resulting high tariffs and import substitution policies. Its economy stagnated and the country entered the 1980s with high levels of public debt, 20% unemployment and a public sector that accounted for a third of the workforce.

Economic reforms starting in 1987 led to reduced public spending, lower taxes and increased competitiveness — especially for global capital. The government made a major effort to lure technology companies such as Intel and Microsoft. In the 1990s, its economy finally began to pick up and soon people were talking about Ireland as the “Celtic Tiger”. In less than three decades, Ireland went from being one of the poorest countries in Western Europe to one of its wealthiest.

One of the areas that helped Ireland attract so much foreign investment was favorable tax policy. Without getting into the details, Ireland enacted policy that made it possible for companies to shift profits on intangible assets like software and patents from higher-tax locations to lower-tax ones. For global technology companies like Apple, this is the main reason why its effective tax rates are so much lower than the prevailing tax rates of its primary tax domicile in the United States.

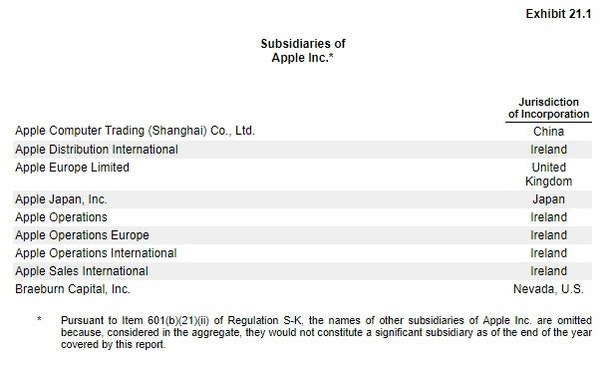

And this is the reason why wee little Ireland features so heavily in Apple’s annual report:

When Apple sells its products overseas, the vast majority of the profits remain offshore. Bringing this cash onshore would require Apple to pay something called a “repatriation tax” to the IRS. Leaving it offshore means that it can delay its payment. Instead, this cash can be used for overseas acquisitions, or perhaps they can wait for the U.S. government to issue periodic “repatriation holidays” to try to coax that money back home. But more often than not, the offshore cash is parked in government and corporate bonds [see Note iii].

Out of approximately $257 billion in cash (and equivalents, including bonds) held by Apple, about 93% of it is sitting offshore.

In any case, the corporate income taxes that Apple does pay — mostly from profits on its U.S.-generated revenue — comes out to about $39 per iPhone. This leaves $243 in after-tax profits.

(5) The Shareholders

Time to head home. I hop on a United flight from Dublin to John F. Kennedy Airport. I head home, fire up my PC, log onto Quora on one screen and my trading platform on another.

This is where we wrap up our journey following these money flows around the world.

The $243 in after-tax profits belongs to the bondholders and equityholders in the company. More accurately, nearly all of it ends up with the equityholders.

Let’s start with the bondholders: Apple has about $115 billion in outstanding bonds that pay lower rates than the U.S. government (less than 3%). It pays out about $3.2 billion in interest expense, which is actually more than offset by over $5 billion it earns from interest income on all of its offshore bonds.

Now some of you might be wondering why such a profitable company like Apple needs to issue bonds. This is where we turn our attention to the shareholders (disclosure: I am one of them).

The reason is because Apple wants to return capital to shareholders by repurchasing its shares. However, to repurchase its shares, it needs to use onshore cash and as we learned above, getting that offshore cash onshore means paying the repatriation tax.

But some enterprising investment bankers figured out a while ago that instead of repatriating the cash, Apple could come up with the cash by issuing onshore bonds that are indirectly collateralized by all of that offshore cash (and all of the other assets of the business). Because it’s Apple, the interest rates are almost negligible. Now Apple can take this newly raised onshore cash and buy back its shares without having to pay the repatriation tax.

On top of share buybacks, Apple pays dividends on a quarterly basis. In FY2018, Apple paid out close to $14 billion in dividends. November 8th, 2018 was the most recent ex-dividend date for Apple shareholders. The cash showed up in my brokerage account a week later. For every share you held prior to that date, Apple paid out 73 cents.

Since announcing its original Capital Return program in 2012, Apple has returned approximately $249 billion to its shareholders via share buybacks and $74 billion via dividends. These share buybacks have allowed Apple to reduce the number of shares outstanding by 25% since 2012. This creates value for shareholders because it means that one share you hold today entitles you to a much larger share of future profits than one share that you held back in 2012 (split-adjusted, of course).

The vast majority of Apple shares are held by Americans, either directly or indirectly via index funds, mutual funds, hedge funds or their pensions. This means that Americans have disproportionately benefited from the enormous amount of value created (and partially returned) by Apple over the years.

Summary

Thank you to the brave few that have stuck with me on my journey all the way to the end. Your reward is the last, and most important table — how all the various money flows get split up by country:

As you can see very clearly, the United States takes the highest share of economic value-add. This is even in the scenario we imagined above where the iPhone is sold overseas (i.e. the U.K.) in a jurisdiction that charges relatively high consumption taxes.

For iPhones that are sold here in the United States, the fraction of economic value-add that circulates back into the American economy is over two-thirds once you factor in the retail operations.

Think about that for a minute: Apple has 132,000 employees (note: this figure includes many lower-paid retail workers), many of whom are located overseas. Yet the American economy is able to capture over 70% of the economic value of an iPhone. Foxconn has well over a million people in China working to assemble iPhones and other Apple products — yet is only able to capture 13% of its value. Let’s keep this in perspective next time we hear complaints about how advanced economies are getting “screwed over” by globalization.

Finally, one of the big ironies is despite the massive surplus value that Apple clearly creates for the American economy, the way that global supply chains and international trade accounting work, Apple products actually add to our bilateral trade deficit with China. This is why it is so important to understand how the money flows really work — so that you can avoid enacting trade and other policies that can end up completely backfiring.

Explanatory Notes

[Note i] The average ASP per iPhone sold was $766, not the £999 retail price. 5.4% of $766 is $41.

[Note ii] On top of hardware sales, Apple also collects significant ancillary revenue: its 30% cut of iOS apps and in-app purchases, search fees from Google, etc. Operating margins on iPhones sold in the store should also have slightly lower margins than those sold online due to lower overhead costs. Finally, margins on iPhones are typically higher than margins on iPads, Macs and other Apple hardware products.

[Note iii] With the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, changes in the tax system have reduced the disincentive for companies to repatriate taxes back to the United States. Following this, Apple announced that it was going to start repatriating its cash over an 8-year period. While it seems likely that this change the onshore/offshore cash dynamic, history has shown how the amazing creativity of investment bankers and accountants when it comes to creating new and sophisticated tax structures.

This was originally published on Quora in December 2018.

Masterfully done!

Please analyse what this iPhone sale in the UK does to the US trade balance with different countries.