What is Warren Buffett's idea of a perfect acquisition?

Why See's Candy was so important to Berkshire Hathaway

On January 3, 1972, Berkshire Hathaway — through its affiliate Blue Chip Stamps — purchased See’s Candy Shops, a vertically integrated candy manufacturer and retailer located primarily in California. It paid $25 million for the business which went on to generate $4.2 million in pre-tax earnings that year [1].

Almost four decades later, Warren Buffett looked back with great pride at this early acquisition:

“Buy commodities, sell brands” has long been a formula for business success. It has produced enormous and sustained profits for Coca-Cola since 1886 and Wrigley since 1891. On a smaller scale, we have enjoyed good fortune with this approach at See’s Candy since we purchased it 40 years ago.

Last year See’s had record pre-tax earnings of $83 million, bringing its total since we bought it to $1.65 billion. Contrast that figure with our purchase price of $25 million and our year-end carrying-value (net of cash) of less than zero. (Yes, you read that right; capital employed at See’s fluctuates seasonally, hitting a low after Christmas.) Credit Brad Kinstler for taking the company to new heights since he became CEO in 2006.

On a $25 million purchase price, See’s Candy had delivered $1.65 billion in pre-tax earnings to Berkshire Hathaway. By itself that is an enormous return but it actually massively understates the aggregate impact it had on the organization.

You see, See’s Candy requires very little in working capital or fixed assets (indeed, ex-cash it was less than zero). Its business model allowed it to increase earnings with very little re-investment back into the business. To generate that $1.65 billion in pre-tax earnings, See’s Candy only had to increase its capital base from $8 million in 1972 to around $40 million by 2007 [2] — which happens to be right in line with the general inflation rate.

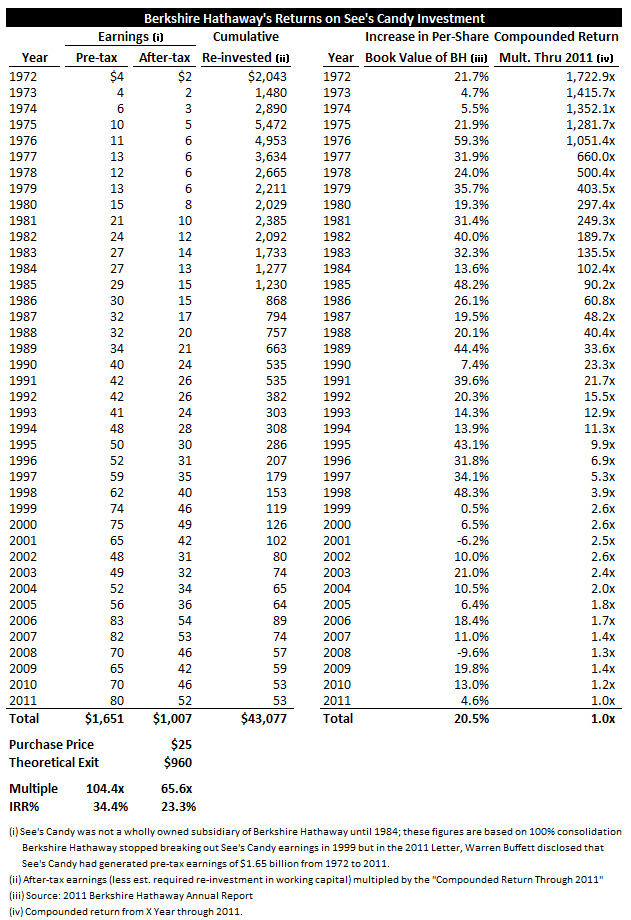

This means that nearly all of those earnings (less taxes) could be re-invested back into stocks, bonds and entire businesses. And Mr. Buffett / Berkshire Hathaway have done a pretty nice job of investing over the years to say the least. The table below shows the cumulative return that See’s Candy has delivered to Berkshire Hathaway factoring re-investment of its excess earnings back into other parts of Berkshire Hathaway:

See’s Candy generated a 23% after-tax IRR for Berkshire Hathaway in the roughly four decades of ownership through 2011. Including re-invested earnings, by the end of 2011, the See’s Candy acquisition made four decades ago accounted for $43.1 billion of Berkshire Hathaway’s book value. This amounts to more than a quarter of Berkshire Hathaway’s book value ($162.5 billion) at the end of 2011 [3].

It is no wonder why Warren Buffett refers to See’s Candy as his “dream business” [2]:

Let’s look at the prototype of a dream business, our own See’s Candy. The boxed-chocolates industry in which it operates is unexciting: Per-capita consumption in the U.S. is extremely low and doesn’t grow. Many once-important brands have disappeared, and only three companies have earned more than token profits over the last forty years. Indeed, I believe that See’s, though it obtains the bulk of its revenues from only a few states, accounts for nearly half of the entire industry’s earnings.

At See’s, annual sales were 16 million pounds of candy when Blue Chip Stamps purchased the company in 1972. (Charlie and I controlled Blue Chip at the time and later merged it into Berkshire.) Last year See’s sold 31 million pounds, a growth rate of only 2% annually. Yet its durable competitive advantage, built by the See’s family over a 50-year period, and strengthened subsequently by Chuck Huggins and Brad Kinstler, has produced extraordinary results for Berkshire.

We bought See’s for $25 million when its sales were $30 million and pre-tax earnings were less than $5 million. The capital then required to conduct the business was $8 million. (Modest seasonal debt was also needed for a few months each year.) Consequently, the company was earning 60% pre-tax on invested capital. Two factors helped to minimize the funds required for operations. First, the product was sold for cash, and that eliminated accounts receivable. Second, the production and distribution cycle was short, which minimized inventories.

Last year See’s sales were $383 million, and pre-tax profits were $82 million. The capital now required to run the business is $40 million. This means we have had to reinvest only $32 million since 1972 to handle the modest physical growth – and somewhat immodest financial growth – of the business.

In the meantime pre-tax earnings have totaled $1.35 billion. All of that, except for the $32 million, has been sent to Berkshire (or, in the early years, to Blue Chip). After paying corporate taxes on the profits, we have used the rest to buy other attractive businesses. Just as Adam and Eve kick-started an activity that led to six billion humans, See’s has given birth to multiple new streams of cash for us. (The biblical command to “be fruitful and multiply” is one we take seriously at Berkshire.)

There aren’t many See’s in Corporate America. Typically, companies that increase their earnings from $5 million to $82 million require, say, $400 million or so of capital investment to finance their growth. That’s because growing businesses have both working capital needs that increase in proportion to sales growth and significant requirements for fixed asset investments.

Looking at See’s Candy we can see what characteristics Mr. Buffett looks for in a “perfect acquisition”:

A business with a defensible competitive edge (in this case, it was the “See’s Candies” brand)

A business that has significant runway to grow earnings (See’s Candy was primarily a West Coast business at the time of acquisition; today it is worldwide)

A business that can increase earnings without having to re-invest significantly back into the business (See’s Candy could raise prices every year without dampening demand)

A business with honest and excellent management (Warren Buffett has continually praised See’s Candy management through the years)

A business that can be purchased at an attractive price (Berkshire Hathaway purchased See’s Candy for approximately 6x pre-tax operating earnings)

Notes

[1] Source: Berkshire Hathaway 1991 Shareholder Letter (All letters since 1977 can be found here: Shareholder Letters)

[2] Source: Berkshire Hathaway 2007 Shareholder Letter

[3] This is only an approximation. See’s Candy was not a wholly-owned subsidiary for its first dozen years as a Berkshire Hathaway affiliate, so not all the benefit of those earnings in the early years accrued to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders. Moreover, See’s Candy itself contributed to Berkshire Hathaway’s compounded returns but it is not easy to isolate Berkshire Hathaway returns ex-See’s Candy — so there is a bit of double-counting. On the other hand, there have been a few acquisitions over the years that have increased Berkshire Hathaway’s aggregate book value via the issuance of stock (i.e. increase in aggregate book value but not an increase in per-share intrinsic value) — most notably the acquisition of General Re in 1998 which increased total shares outstanding by around 21%.

This was originally published on Quora in December 2017.