What is the economic significance of BRICs?

The emerging markets acronym

The individual BRIC economies are clearly significant but the BRIC grouping itself was not — at least not in the same way other groups are like the OECD or Group of Seven.

BRICs stood for Brazil, Russia, India and China (later South Africa was added). Economically, there wasn’t actually much commonality among these four (later five) economies and try as they did to “make it work” the artificial grouping never really amounted to much. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see how after a flurry of excitement and coordination, each country has really gone down its own separate economic path.

The Acronym

In late November 2001, economist Jim O’Neill (then Head of Global Economic Research at Goldman Sachs) penned a report entitled “Building Better Global Economic BRICs” highlighting these four large emerging economies and forecasting that they would likely account for a rising proportion of global growth in the coming years. I remember this report quite clearly because I had just started working as an investment banking analyst in Hong Kong and some of the first projects I worked on were related to China, Russia and India — three countries I really knew very little about at the time.

This prediction turned out to be correct as over the next decade the growth of emerging economies outstripped the growth of developed economies. Even so, the reasons for why these four countries were chosen (and why others were excluded) did not ever seem to extend beyond the superficial.

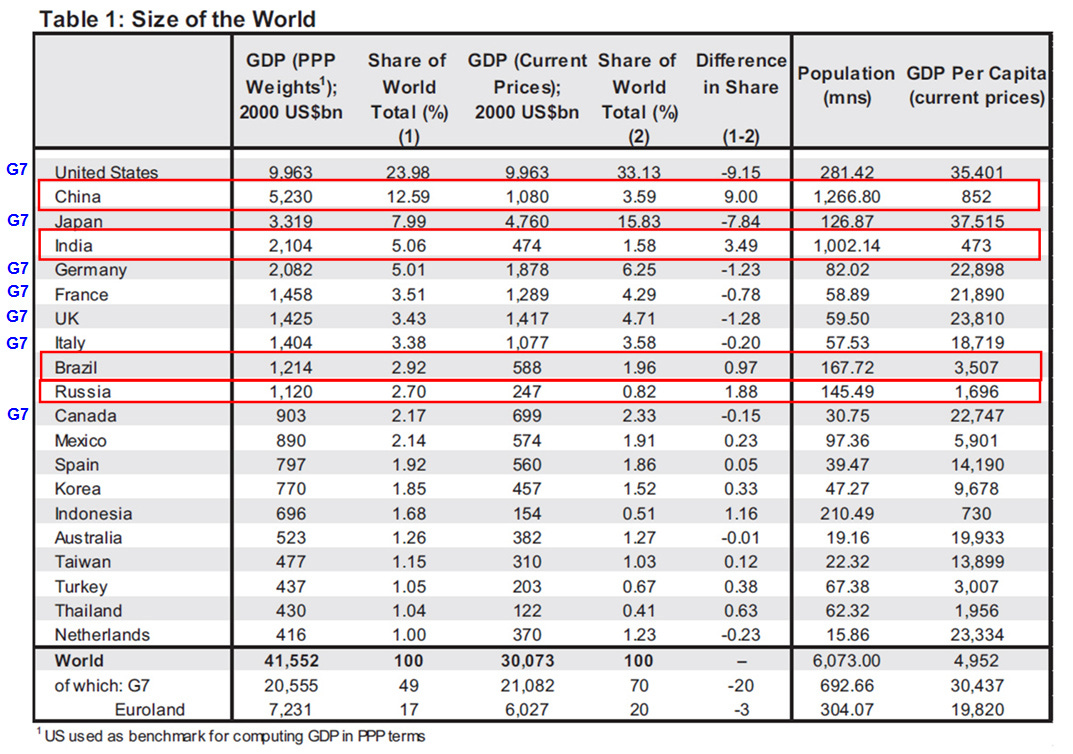

There was one really obvious reason why these economies were chosen — these four were the largest economies in the world that were not a member of the Group of Seven. Here is a table from the BRICs report (with my annotations in red and blue):

But then one has to ask … why did it stop at Russia? What about Mexico or Indonesia? After all, economically Mexico has more in common with China than Russia or Brazil and the same can probably be said about Indonesia with India.

I have a sneaking suspicion that the reason why it was cut off at the four was because adding Mexico would have messed up the BRIC acronym. “BRICM” or “CBRIM” just don’t roll off the tongue as well!

Developed vs. Developing

To be fair, the “not being part of the G7” part was somewhat meaningful. The post-WW2 global economy had been dominated by institutions that had been established and controlled by the G7 countries. For example, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was effectively controlled by the E.U., the World Bank by the United States and the Asian Development Bank by Japan.

Mr. O’Neill correctly identified that emerging economies were likely to take an increasing relative share of the global economy and as such, would also likely want to have greater say and influence in setting the global rules. Indeed, the BRICs report contemplates whether the G7 might eventually be expanded into the G8 or G9.

And that is exactly what happened. Led by China, emerging economies became a huge investment theme in the ensuing years. China’s economy grew in the teens and the country became a ravenous consumer of nearly everything. Commodity prices skyrocketed, buoying Brazil and Russia. India started to see its growth inflect following its economic reforms in the early 1990s. BRIC became synonymous with unfettered economic growth and Mr. O’Neill became known as “Mr. BRIC” himself — not to mention eventual Chairman of Goldman Sachs Asset Management.

The four countries began to wonder if BRIC could be more substantive than just a clever marketing acronym — and if locking arms together would help them advance their individual economic interests. In September 2006, foreign ministers from the four BRIC countries met in New York at the UN to kick off a series of high-level meetings. The first full-scale diplomatic meeting was held in Russia in June 2009. South Africa officially joined the group in 2010 and the BRICS Forum was officially formed in 2011. There was talk about establishing a “New Development Bank” that would rival existing international institutions like the World Bank or ADB.

But things sort of peaked there and the BRICS grouping has since fallen by the wayside. I don’t really hear much about it anymore.

The Usual Suspects

What happened is that the world had changed. By 2013, these four/five economies realized that they really did not have much in the way of economic commonality or similar economic interests:

The Russian and Brazilian economies are resource-rich and heavily dependent on the prices of commodities (e.g. oil, iron, soybeans). China and India are large commodity importers.

China and India each had over a billion people; Brazil and Russia were both less than a sixth the size with very different demographics and population pyramids.

The Russian economy was already industrialized but dealing with the after-effects of botched “big bang liberalization” that left much of the economy in the hands of a small oligarchy.

Brazil had started industrializing earlier but now seemed to be stuck in a bit of a “middle income trap”.

China was rapidly industrializing on the back of global trade and employing “financial repression” to prioritize infrastructure development.

India was starting from the lowest base, still in the early stages of the rural-to-urban migration and trying to shake off the heavy bureaucratic legacy of the Licence Raj.

I’m not even going to go into South Africa whose economy is about the same size as a large Chinese city.

The economic weightings within the group were disproportionately weighted towards the two poorest countries, China and India, simply by virtue of their massive populations.

I think the final blow for BRIC came with the slump in commodity prices following the Global Financial Crisis, culminating with the crash in crude oil prices in 2014–15. This hit the Russian and Brazilian economies particularly hard while China and India saw significant benefit — the BRIC countries were literally at opposite ends of the spectrum from each other on this economic issue.

Looking back with the benefit of hindsight, the whole BRIC grouping kind of reminded me of the 1995 film The Usual Suspects where a group of guys are thrown together seemingly randomly and end up spending most of the rest of the movie trying to figure out why.

China strikes out on its own

The other thing that happened is that China ended up dwarfing the other BRIC countries, accounting for most of the group’s growth: 63% of GDP growth in PPP terms — and an even higher percentage in nominal terms:

Now the largest or second-largest (depending on whether you look in terms of PPP or nominal) economy in the world, China was getting increasingly frustrated with its lack of proportional influence in international organizations such as the IMF and World Bank. Being part of the BRIC grouping did not seem to advance its interests one bit on this front.

So at some point, China said “Eff this” and decided to take things into its own hands. Things really accelerated after Xi Jinping took over in 2013: In quick succession, China established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (established October 2014), the Silk Road Fund (December 2014) and announced its “One Belt One Road” vision for the future of global trade (related: What do you think about the AIIB?). The other BRIC countries are participating in varying degrees in these organizations but at the end of the day, they are really China-led initiatives.

In May 2016, “Mr. BRIC” himself looked back and gave his own post-mortem assessment on the term he coined: I got 2 out of 4 countries right, ‘Mr BRIC’ Jim O’Neill says. Economic forecasting ain’t easy and batting 0.500 is pretty darn impressive! Even though there was very little in the way of actual economic similarities tying these four countries together, BRIC did end up having a major influence on financial markets and the ultimate economic development of its member countries.

This was originally published on Quora in December 2017.