What can the US do to bring back manufacturing that has been outsourced in China?

It's about looking forwards not backwards

“I skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.” — Wayne Gretzky

We will be fine if we make sure we continue to look ahead and not backwards.

By almost every measure, America is in the lead. Leaders do not stay ahead by looking backwards. They keep their eyes fixated ahead with confidence and determination.

Job creation is actually really easy if you do not care about the quality of the jobs. In fact, the easiest way to “create” jobs is by turning the clock back on progress. In his 2015 Annual Letter, Warren Buffett wrote about the railroad industry, a topic he knows a little something about:

In 1947, shortly after the end of World War II, the American workforce totaled 44 million. About 1.35 million workers were employed in the railroad industry. The revenue ton-miles of freight moved by Class I railroads that year totaled 655 billion.

By 2014, Class I railroads carried 1.85 trillion ton-miles, an increase of 182%, while employing only 187,000 workers, a reduction of 86% since 1947 …

… As a result of this staggering improvement in productivity, the inflation-adjusted price for moving a ton-mile of freight has fallen by 55% since 1947, a drop saving shippers about $90 billion annually in current dollars.

Another startling statistic: If it took as many people now to move freight as it did in 1947, we would need well over three million railroad workers to handle present volumes. (Of course, that level of employment would raise freight charges by a lot; consequently, nothing close to today’s volume would actually move.)

Our own BNSF was formed in 1995 by a merger between Burlington Northern and Santa Fe. In 1996, the merged company’s first full year of operation, 411 million ton-miles of freight were transported by 45,000 employees. Last year the comparable figures were 702 million ton-miles (plus 71%) and 47,000 employees (plus only 4%). That dramatic gain in productivity benefits both owners and shippers. Safety at BNSF has improved as well:

Seventy years ago, a little over 3% of the U.S. workforce was employed by the railroad industry moving freight and passengers around the country. Today, only one-tenth of 1% of the workforce is involved in the railroad industry, yet it moves nearly three times the amount of freight around the country. If we wanted to create three million new jobs, all we would have to do is get rid of seven decades worth of progress and productivity improvement.

Obviously, these aren’t the types of jobs that we should aspire to create.

What we need to do is create the next Apple. Steve Jobs imagined the future and willed it into reality. He took Apple where he thought the puck was going to be.

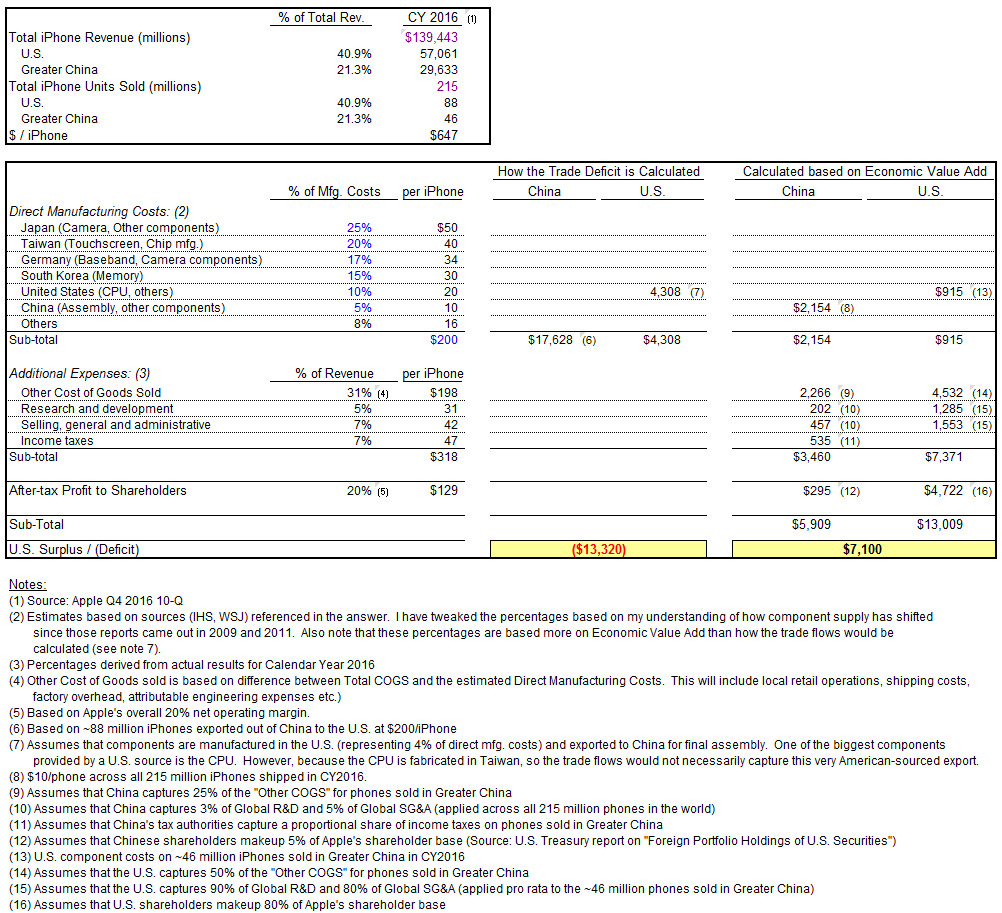

Nearly all of Apple's revenue today comes from products that did not exist a decade ago. In another article I calculated how much economic value a single product (the iPhone) brings in from a single region (China) on its own:

The $7.1 billion iPhone surplus supports a lot of high-quality American jobs: Something like 47,000 well-paid jobs in Cupertino at $150,000/person; not to mention all of jobs in the surrounding community that are indirectly supported by those high wages. And this is just hardware sales of a single product from a single region — it doesn’t include iPads, Macs, App Store purchases etc.

We need more iPhones. We need to come up with more Apples.

It should not be about “bringing jobs back” but more about figuring out what we will need in the future and making sure we are ahead of the pack in providing it to the world. If we focus too much on trying to recover all of the old jobs from China, we run the risk of watching them skate right by us — I guarantee that they are heeding Mr. Gretzky’s advice and laser-focused on the future. Same goes for the Germans, the South Koreans and the Japanese.

We also need to recognize that outsourcing (along with automation) have hit some groups of Americans really hard, especially in places like the Midwest and rural communities in the country’s heartland. It is okay to slow down a bit on outsourcing so that we can give time for our hardest-hit communities to heal. While lowering tariffs from 50% to 10% may have created a ton of value for the country, maybe the benefits of fully removing them is far outweighed by the disruption it may cause to a specific American industry, the workers it employs and the communities to which they belong. We are a wealthy country and we can afford to look after each other.

If we want to reap the benefits of outsourcing, we must be prepared to properly handle the inevitable disruption that comes with it. Perhaps that means coming together in a bi-partisan manner to figure out how we can best support fellow Americans through difficult transitions. Or being proactive by economically involving displaced workers and communities in the next-generation of products, technologies and services that our amazing entrepreneurs come up with.

But slowing down does not mean looking or going backwards. We can slow things down a bit yet still be laser-focused on where that metaphorical puck is going to be ten, twenty, or even one hundred years down the line.

This was originally published on Quora in February 2017. Also published in Forbes.