What are the results of 1997 Asian Financial Crisis?

The separation of the Best from the Rest.

Following the Asian Financial Crisis, certain Asian economies such as South Korea and Taiwan recovered and were able to continue developing and achieve enough escape velocity to break out of the “Middle Income Trap”.

Other former “miracle” economies such as Indonesia and Thailand have recovered but have not yet been able to elevate themselves to the next level. An analysis of development policies in these economies yields some clues as to why some economies were more successful than others in the years following the Crisis.

In 1993 – four years before the onset of the Asian Financial Crisis – the World Bank released a landmark study called the “The East Asian Miracle : Economic growth and public policy” which highlighted a group of countries they dubbed the “High Performing Asian Economies (HPAEs)”: Hong Kong, Indonesia, South Korea, Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. Looking at data across a number of economic, HDI and other factors, the study tried to figure out why these once desperately poor economies had been able to grow much faster in the post-WW2 period compared to economies in Africa and Latin America:

Since 1960, the HPAEs have grown more than twice as fast as the rest of East Asia, roughly three times as fast as Latin America and South Asia, and five times faster than Sub-Saharan Africa. They also significantly outperformed the industrial economies and the oil-rich Middle East-North Africa region. Between 1960 and 1985, real income per capita increased more than four times in Japan and the Four Tigers and more than doubled in the Southeast Asian NIEs. If growth were randomly distributed, there is roughly one chance in ten thousand that success would have been so regionally concentrated.

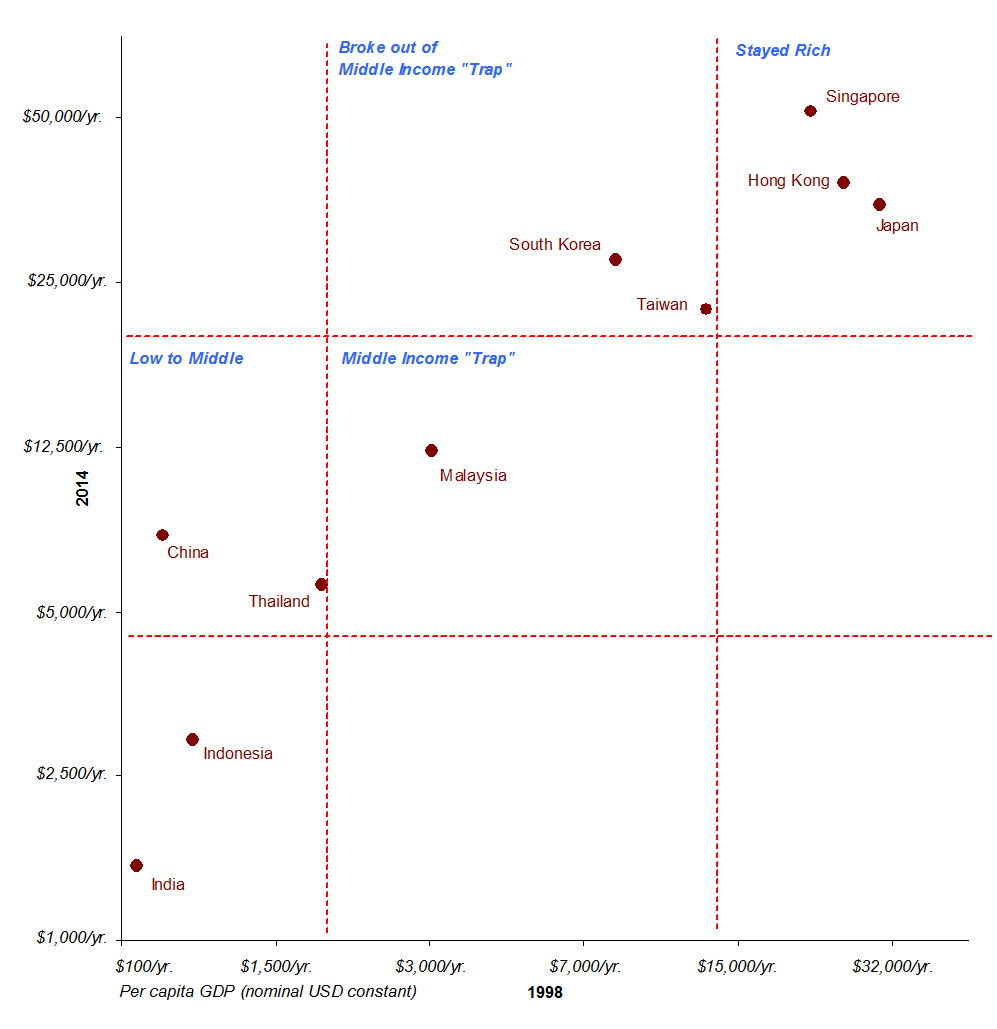

However, as we can see in the chart below [1], following the Asian Financial Crisis, some of these countries (e.g. Thailand and Malaysia) have gotten varying degrees stuck in the “Middle Income Trap“ area while others (South Korea and Taiwan) have broken out and become wealthy economies.

As it relates to developmental economics, the challenge is trying to figure out what countries like South Korea and Taiwan did differently from others that allowed them to break out of the “Middle Income Trap”.

In this article, I explore some of the key developmental policies that South Korea and Taiwan implemented differently, namely successful land reform and an export-oriented industrialization approach. But as I have talked about in other answers (Will India be able to avoid the “Middle Income Trap”?), I think the “grand unifying theory” of developmental economics is figuring out how to harness the entrepreneurial energy of a country in ways that are beneficial to both the entrepreneur and broader society:

Every country has enough entrepreneurial energy. The difference between success (getting rich) and failure (staying poor) lies in their ability to harness this energy in a manner that was not only profitable for the entrepreneur but beneficial to society at large.

Because of differences in history, culture, geography etc. the specific policies that each country chooses may differ, but the underlying principles should stick to this theme as much as possible.

For example, many Southeast Asian countries that have gotten stuck in the “Middle Income Trap” were former European colonies. When they gained independence, the domestic elite in these countries that the Europeans had relied on to run the colony took over political and economic control of these economies. Many of them were large landowners and they naturally did their best to block efforts to implement wide-scale land reform where their land holdings might be taken away from them.

Subsequently, these countries were unable to improve agricultural productivity as much as that seen in South Korea and Taiwan and even more significantly, they ended up with a small percentage of the population holding vast amounts of wealth while millions ended up in semi-feudal conditions scraping along at a subsistence level and unable to build up any wealth.

As these countries industrialized, many of the domestic elite used political connections to win domestic licenses to sell goods that where most of the manufacturing value-add took place in foreign countries. These could be very profitable franchises for the business owner, but they did not create many valuable local jobs and did not have much incentive to innovate as they had zero competition. In effect, they were rent-seeking franchises that simply transferred wealth from one pocket of society to their own without enlarging the economic pie. A country simply will not be able to break out of the “Middle Income Trap” under these conditions.

This contrasted largely with the experience in South Korea and Taiwan. While the governments did allow their nascent industrial companies to grow into adolescence in a relatively protected environment, at that point they were forced out into the global export markets to “sink or swim”.

Many failed but failure is an important part of the power of the market – it creates a self-reinforcing and relatively unbiased mechanism to separate and reward the “good” entrepreneurs from bad ones. This type of behavior enlarges the economic pie (benefiting not just the entrepreneurs) and helped drive these companies into the league of “high income” nations/economies.

Notes

[1] Data points are based on GDP per capita (nominal) in U.S. Dollar terms (source: World Bank). I calculated each country’s per capita GDP relative to the per capita GDP of the United States and converted to a log scale. This was similar but not exactly the same as an approach used by the Economist. The classifications for “low income”, “middle income” and “high income” levels correspond roughly with the World Bank’s classifications.

This was originally published on Quora in March 2016.