What are the geopolitical implications of oil dropping below $30 per barrel?

Winners and losers

Oil has played a significant role in most of the major geopolitical events of the modern era. For instance, it was the major reason why Germany split its invasion force during Operation Barbarossa which led to its defeat on the Eastern Front (and ultimately the entire European theater). Getting its oil supplies cut off spurred Japan to attack Pearl Harbor and later over-extend itself in Southeast Asia, ultimately leading to its defeat in World War II. OPEC-induced oil shocks led to economic stagflation in the 70s; later, the low-price environment in the 80s led to fiscal issues in the Soviet Union and ultimately the fall of Communism.

So one thing is for sure: major changes to oil supply, demand and price will almost certainly have major geopolitical implications down the line. The tough part is predicting what these things are and when they might happen. In fact, given how many important factors impacting oil are determined by a small group of people sitting in the room in Vienna, I would say it is nearly impossible to predict with any sort of accuracy what happens over the short to medium-term.

I think the best you can do is think about some of the important aspects and speculate about potential scenarios that might result over the long-term. It is also useful to look back at history to see how things played out (and over what timeframe) back then.

Let’s first think about the winners and the losers of lower oil prices:

Winners

Major oil importers like Japan, South Korea, China and India are saving hundreds of billions of dollars a year with crude oil priced at $40-50 compared to when crude oil was priced at $100 for much of the last decade. These importers are the big winners.

India is probably the biggest winner on a relative basis. They import around 4.3 million barrels per day, so a $50 drop in crude oil prices means $200 million per day in aggregate savings. For a country that has historically run major trade deficits, contributing to persistently high inflation, this is a major windfall that is allowing Modi, Raghuram and Company to concentrate on other economic issues.

The United States is also a big winner because we are one of the largest net importers of petroleum products. However, because we are also the world’s largest oil producer, there are also losers throughout the economy, like shareholders and bondholders in upstream oil producers. Many oil companies have already gone bankrupt and I expect many more to do so as low oil prices persist. This means the loss of jobs and adjustment for many areas of the country that up to even 18 months ago were considered economic bright spots. This has also created a heightened sense of risk amongst energy investors, and this fear is trickling into other sectors, especially those that touch energy like industrials.

Europe (with the exception of North Sea producers like the U.K. and Norway) is another winner, saving billions of dollars a year from lower oil prices.

Losers

The biggest losers are major oil exporters like countries in the Persian Gulf, Nigeria, Norway, Iran, Russia, Canada, Mexico, Venezuela, Libya and Algeria.

The more reliant the country’s economy and government budget is on oil, the more vulnerable it is:

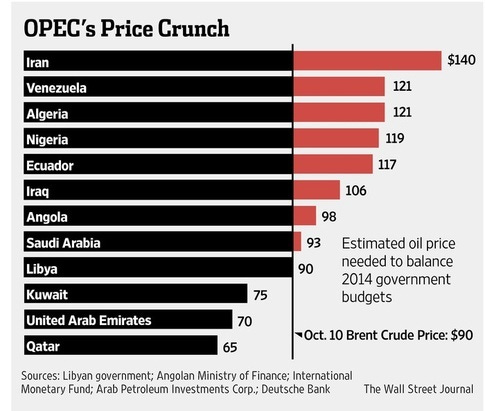

The chart above is from October 2014 when crude oil was trading at $90. Currently, prices are around $30. Some countries have hedged some of their oil production, or sell oil based on longer-term contracts that do not automatically re-price based on spot prices. But eventually hedges run out, and long-term contracts conform to market prices. By now, almost all of the major oil exporters are running large fiscal deficits as a result of low prices, which forces them to draw on their sovereign wealth funds and foreign reserves, or borrow on the international markets.

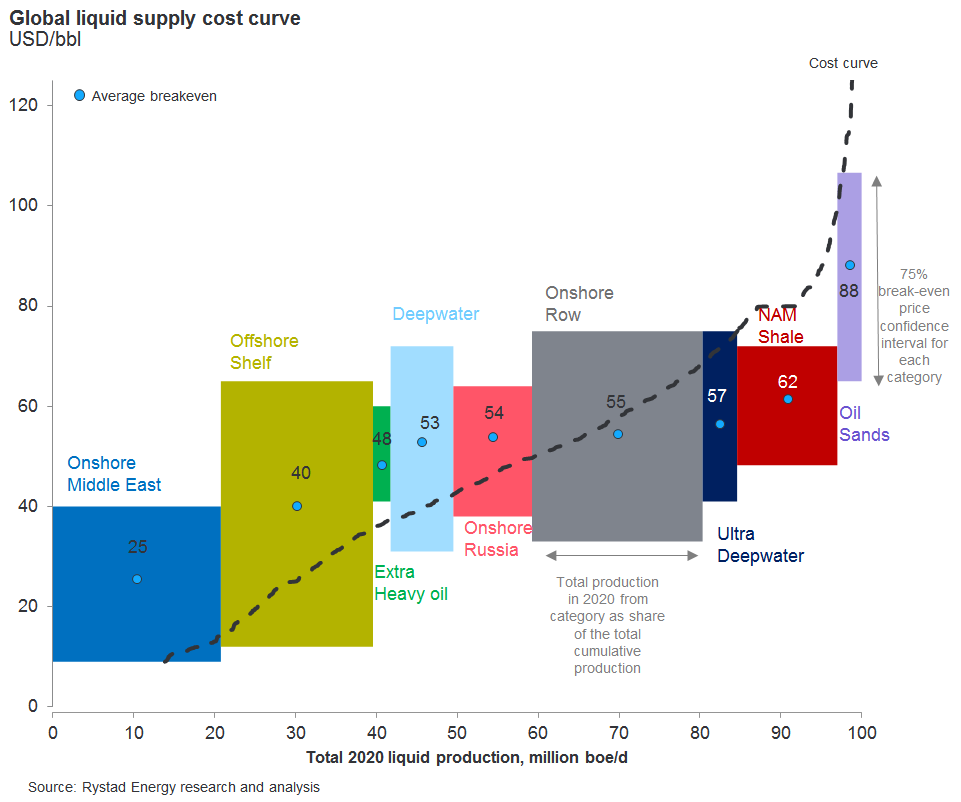

The other factor to consider is how expensive it is to extract and refine a country’s oil reserves. For example, Canada’s massive oil reserves are largely tied up in the Athabasca oil sands in Alberta and it is (i) very expensive to extract the oil and (ii) relatively expensive to transport and refine for end markets. At $30, it does not make economic sense to extract oil from oil sands. Venezuela’s “heavy” oil costs a lot of money to refine into products that consumers can use. As a result, their product is priced at a significant discount to the market price, which means some of their oil is being sold for much less than the already low $30/barrel benchmark price.

On the other end of the scale, in Saudi Arabia, getting oil out of the ground is like sticking a straw in a juice box i.e. extremely cheap. From this perspective, Saudi Arabia is in one of the best positions to weather a prolonged period of low oil prices.

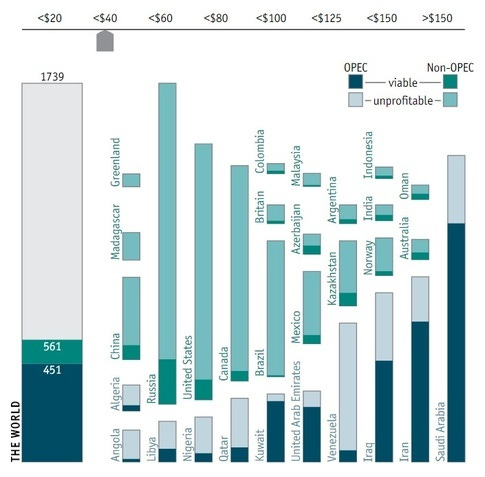

This interactive chart from the Economist just came out that illustrates this same concept from a country/regional perspective:

Geopolitical implications

The more diversified oil exporters like Canada are much less dependent on oil revenue and government budgets have thus far been able to handle the drop in oil-related revenue. However, “pain” is showing up in watching their currencies depreciate and dealing with major job losses in the oil and commodities sector. At this point, even diversified economies like Canada that are major commodities exporters are struggling to avoid a recession. Painful, but not life-threatening.

For less diversified economies whose government budgets depend almost entirely on the oil sector, it really is a question of “who blinks first?” The ability for major exporting countries to sustain fiscal deficits is based on their ability to (i) cut government spending and (ii) draw from foreign reserves they have saved for a “rainy day”. Already, you are seeing Saudi Arabia announce major cuts to their government budget, cutting government sinecures, reducing subsidies and benefits etc. And they are probably the strongest major OPEC country, capable of holding out the longest.

Prolonged economic and fiscal issues eventually lead to social unrest. Nobody likes to see their standard of living decline. In a tinderbox region such as the Middle East, this has the potential to flare up into crisis in a flash. The last time oil prices dropped this quickly and stayed low for a sustained period of time was during the 1980s and in no small part contributed to the breakup of the Soviet Union and the eventual fall of the Communist Bloc i.e. the most significant geopolitical event of my generation. The longer this situation persists, the more likely something breaks. It’s just really hard to say who or when. But I’ll try anyway!

Based on a combination of (i) fiscal position (ii) quality of oil assets and (iii) underlying social dynamics, within OPEC the most vulnerable major countries are Iraq and Venezuela. With its large, youthful and fast-growing population and the risk of having groups like Boko Haram mucking things up, I suspect Nigeria is dicey as well.

I feel like Iran is relatively safe – they were able to survive under major economic sanctions without regime change, and now those economic sanctions are being lifted (although one can argue that they had no choice because the situation was so dire). I think Saudi Arabia is relatively secure behind massive energy and financial reserves, but its rapidly-growing, under-employed youth population and potential succession issues could lead to something more serious. Then again, if things get to the point where Saudi Arabia is blowing up, the surrounding situation is probably already pretty bad.

For the U.S. because of our massive shale reserves, we depend far less on the Middle East than we did before. Strategically, this is a huge positive. How quickly things change: many forget that Energy Security was one of the most important issues during the George W. Bush presidency. From this perspective, we are coming out of this much better than the Europeans, who don’t have the same shale potential and also sit much closer geographically to the Middle East and Russia – with the Syrian migrant crisis, we can catch a firsthand glimpse how much more dangerous this is for them.

By the way, if we really want to press this advantage, there’s never going to be a better time than now to phase in fuel tax increases that can not only help curb future consumption but also spur further progress on fuel efficiency standards and breakthrough technologies that will ultimately impact demand the most in the long run. Lowering long-term demand is ultimately the best path to Energy Independence. I hope Mr. Obama is listening.

China and India are also big winners. Both countries import vast amounts of crude oil – I expect China to surpass the U.S. in crude oil imports sometime in the near future and India will probably at some point as well. Both countries are already savings hundreds of billions of dollars a year with oil prices >$50 lower than they were 18 months ago. This softens the blow from a weak export environment for China, which is seeing its merchandise surplus widen even as exports flatline. For the country which is in the middle of a challenging economic transition, this is very helpful. India, too, is trying to re-make its economy. In the past, persistent and growing trade deficits and high inflation have been their policymaker’s key challenge. With their oil import bill more than cut in half, this helps solve those two issue and allows more breathing room to execute in other areas, particularly manufacturing and attracting foreign direct investment. Both countries (especially China) like the United States is geographically insulated from any turmoil in the Middle East and/or Russia that might be caused by persistently low oil prices.

This was originally published on Quora in January 2016.