What is the intrinsic value of gold?

Wealth signaling

The intrinsic value of gold is based on its primary use case today as a way for humans to signal wealth — expressed mainly through ornamental jewelry — and to a lesser extent from certain industrial uses.

It also gets value as a reliable “store of value” but in my view this component is ultimately derived from these first two real-world use cases.

In the past, gold was also a fantastic medium of exchange, especially in “trust-less” foreign trade but modernity and technology have negated this aspect of its intrinsic value.

This is the second in a three-part series where I will explore the intrinsic value of various forms of money: Fiat currency, gold and Bitcoin. Please refer to my blog post for some of the summary observations:

Blockchain and exploring the intrinsic value of money

In the third and final piece of this series (still to come), I will discuss the “intrinsic value of Bitcoin”. In that one, I will provide my take on John Pfeffer’s “(Institutional) Investor’s Take on Cryptoassets” paper which attempts to size Bitcoin and the larger crypto asset market by framing it as a potential replacement as a “store of value” for gold and possibly even fiat currencies. I hold a slightly different view and much of that answer will refer back to concepts that I discuss in more detail in these first two answers about fiat currency and gold.

In the beginning, there was Barter

From the dawn of homo sapiens through the Mesolithic era, humans lived together in small villages or hunter-gatherer groups, and this economy was communal (i.e. trusted) and non-specialized. There were only a handful of major tasks (e.g. hunting, farming, making clothes, raising children) and since everybody within the group knew each other, assets and work were generally shared within the group.

Trade between different groups (i.e. “trust-less”) would take place using the barter system. An illustrative trade route could be a mountain village that trades animal skins to a village by the lake for fish. Trade was quite rare.

The issues with the barter system are related to its extremely high frictional costs. It is rare for two individual parties to be able to need exactly what the other party requires at a specific point in time. For example, it is hard for a blacksmith to trade his smith services for a loaf of bread from the baker, because the baker may not own a horse.

So while the barter system worked fine when people lived in small, individual groups where everyone knew and trusted each other, to get to the next level of civilization (small towns and cities), humans had to innovate.

Thus the invention of money.

Money facilitated trade because it reduced the friction costs of trade. Now you could have a common medium of exchange that allowed the blacksmith to trade his services indirectly to the baker for some bread. As anyone who has ever played Civilization knows, money (a.k.a. currency) was a key invention that enabled the rise of small towns and cities.

Money took many forms — from cowry and stone to metals and other materials. Money developed independently in multiple regions and while it may have differed in form, the general concept was the same. But over time, one form of money separated itself from the pack.

The Rise of Gold

Gold has several interesting natural properties that make it particularly useful as money, including:

Scarcity — there was not a lot of it

Anti-counterfeit — easy to identify and authenticate

Portability — easily transported

Divisibility — low melting point, easy to break into smaller pieces

Indestructibility — it will not rust, die or rot

Over the years, these qualities were increasingly recognized by societies around the world, especially as these societies became more sophisticated. Towns became cities, cities became city-states and city-states became empires.

Gold has been used as a medium of exchange and store of value for thousands of years. It was independently recognized in multiple cultures around the world. This made it particularly useful for facilitating trade between different states (i.e. “trust-less”).

It also developed and became recognized as a signal of wealth. Gold could be fashioned into ornamental jewelry or given as high-value gifts. At its core, gold was very useful in fulfilling the innate human need to signal wealth and reinforce social hierarchies.

For many centuries, the intrinsic value of gold was supported by multiple use cases — as a medium of exchange, as a signal of wealth and as a store of value (which as I will go into more detail below, is more of a derivative use case based off the first two).

Gold’s intrinsic value as a medium of exchange is disrupted

As the modern nation-state emerged, modernity and progress began to chip away at some of gold’s advantages as a medium of exchange.

Gold’s relative scarcity meant that it was always used alongside other “cheaper” forms of money as a medium of exchange. For example, as nation-states and the modern banking system emerged, paper money became more widely used. Gold could still be used as a medium of exchange for foreign transactions as holding paper bills from your trade partner was not all that useful (hard to convert to real-world value; devaluation risk).

As we entered the electronic and digital age, money transitioned from a physical concept to a more abstract one. Foreign trade could be conducted by simply updating ledgers — first physical ones and then eventually digital versions. As with most things, this was mainly driven by economics and convenience — gold became an expensive way to transfer value compared to writing checks, sending wires and issuing IOUs backed by nation-states.

As a result, gold’s intrinsic value as a medium of exchange gradually faded away as it became easier to do business using other forms of money. Fiat currency was backed by gold (meaning you could exchange bills for physical gold) but even most of these types of monetary systems were dismantled in the first half of the 20th century.

Gold and the utility of wealth signaling

Worldwide gold stock is around 165,000 metric tons (5.3 billion troy ounces) [1]. At $1,340 per troy ounce, this is equivalent to around $7.1 trillion in today’s dollars.

Gold’s primary use cases are jewelry, official reserves, investment purposes (gold bars) and industrial applications:

As shown above, jewelry is clearly the dominant use case for gold today. When you boil it down to First Principles, wearing jewelry is really just a way for humans to signal wealth to others in a socially acceptable way. It has been socially accepted for thousands of years and will in all likelihood continue to be well into the future. The very human need to maintain social hierarchy is an essential element of who we are.

Now compare gold’s wealth-signalling utility to Bitcoin and crypto-currencies. As “attractive” as the sweaters below might look, do you really think this unique method of expressing “crypto wealth” is anything more than a fad or meme, and will still persist many years in the future? Will it be socially acceptable (as gold jewelry has been) in a different time, under different conditions? Probably not.

Source: NY Times. You don’t even need to own any of it to wealth signal!

Gold as a Store of Value

Moving on to the next use cases, the 18% of gold sitting in the official reserves of nation states and 16% sitting as private investments represent the use of gold a store of value.

The store of value concept is quite misunderstood in my view. For example some commonly cited reasons for holding gold are as a hedge against inflation or getting screwed by an “evil” banking system. But if we dig deeper and evaluate the store of value concept from a more fundamental “First Principles” type framework, we can better understand what drivers are really at work here.

There are several elements that you need to think about when trying to rationally determine whether something is a good store of value:

First, you need to specify a timeframe i.e. when you expect to retrieve value. Is it three months? Five years? Five decades?

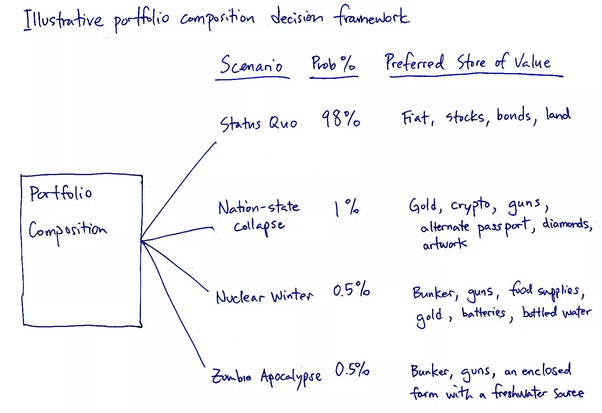

Second, you need to specify the scenarios that you are trying to “solve for” and apply a probability to it. Are you worried about the collapse of your nation-state? The collapse of the banking system? Nuclear war? Zombie apocalypse? What are the probabilities of such events?

Third, you need to consider how your proposed store of value (gold, fiat, crypto, stocks, bonds, land etc.) will “perform” in such a scenario.

Depending on your timeframe and scenario, the various options for storing value may differ in attractiveness.

For example, if the timeframe is six months from now, unless your country is suffering from true hyper-inflation, traditional fiat currency does a pretty good job of storing value. Even if you live in a country that is suffering from hyper-inflation, another more stable country’s currency may be a good store of value.

But if the timeframe is say ten years, even in stable nation-states you may be worried about the long-term effects of inflation or even a de-stabilizing even like the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. Under such a scenario, maybe gold is not such a bad way of keeping its value.

Usually when people think about store of value, they are more concerned about retaining value than growing it. And gold has done a good job of retaining value over long periods of time as it has some inflation-resistant properties. Now it has done a very poor job of growing value over time (e.g. compared to stocks and bonds) but people who hold it in their portfolios tend to be more focused on the downside than upside.

Let’s consider a scenario where many nation-states collapse due to war or some other calamity. Human society goes backwards, perhaps something depicted in the TV Series Revolution. Any fiat money, stocks, bonds, crypto assets that you held would most likely be worthless.

But even a more backwards society would still have some sort of an economy. And one can even imagine these more primitive economies falling back on traditional forms of money like gold. Indeed, it might even regain its standing as a commonly used medium of exchange under such a society.

Here’s another way to illustrate what I am saying here — boiling all of this down into a decision-framework on how to think about various stores of value in the context of these various scenarios:

The other misunderstood aspect of “store of value” is that “store of value” itself must ultimately be derived from some form of real-world utility. As mentioned above, I believe that gold’s fundamental use case is really based on the human need to signal wealth and the implicit understanding that this human need will persist for as long as we walk the earth is what imbues gold with the quality of being a good store of value. If you do not think such utility will last in the future, the item will not be a good store of value.

Fiat currency is a good store of value as long as people believe in the resiliency of the nation-state because it derives all of its intrinsic value from the nation-state itself. However, if the nation-state collapses, its fiat currency becomes worthless.

From this perspective, gold is a superior store of value to fiat money over very long periods of time, because whereas nation-states collapse on a fairly regular basis, the innate need for humans to signal wealth in a social hierarchy will likely exist to the end of civilization itself.

To illustrate this, imagine you are Rip Van Winkle settling in for a long one hundred-year nap. You want to be able to wake up 100 years from now and still have some sort of asset base. So you have $10 million in assets and have a choice of either burying that amount in physical $100 bills or gold. With physical bills, there is a high likelihood that the bills will either (i) rot away (ii) be inflated away or (iii) be de-monetized by the regulatory authority (like what happened in India recently). But with gold, there is a pretty decent chance you can retrieve it and still live be able to live a decent life in the year 2118.

Epilogue

Outside of purchases of jewelry or gifts, I have never “invested” in gold. Nor do I plan to — I put “invest” in quotes because I do not even consider purchasing gold to be investing. I live in a very stable nation-state and I find fiat currency to be a perfectly reliable store of value for my short-term needs. For example, my rule is to hold at least six months of your monthly outlays in liquid cash for that “rainy day” (albeit non-catastrophic) scenario.

Over the long run, instead of being focused on retention of value, I am very much focused on compounding wealth — and I find that investing in businesses and entrepreneurs through stock and private investments is the best way to maximize wealth creation for me.

My approach to evaluating true disaster scenarios like nuclear war or a “zombie apocalypse” is to not think very much of them at all. First, I think the chances are quite low. Second, because if they really do happen, there is probably a decent chance that we don’t make it anyway and frankly I am unsure if I would even want to live in such a dreary world. Even if we survive, I think — as I alluded to in the decision-making heuristic above — it might have been better all along to “invest” in guns, a bunker and/or an alternative passport instead of gold.

However, I do understand that other people may view this very differently, or may simply apply a higher probability to such a catastrophic event than I do. I also understand that most people who have invested in gold have probably not thought as much about breaking down this “store of value” question as I have. Indeed, perhaps the most substantive takeaway on gold is that the permanence of irrational thinking in the world, especially as it relates to gold — and the extremely high likelihood that this irrationality is permanently ingrained in our DNA just like the need for social hierarchy.

Note

[1] Source: All The World's Gold

This was originally published on Quora in February 2018.