The cadence of reform in China

Economic and political cycles

One concept that is important for those that follow the various economic reforms in China is that there is a fairly predictable cycle in which reforms are conceived, planned and carried out. Typically, this structure follows a certain cadence that is to some extent tied to China’s political cycle (i.e typical ten-year term, divided into five-year halves).

As some of you may have suspected, I am alluding to the Five-Year Plans that China has used for economic development planning since the first one in 1953.

When I first learned about this aspect of Chinese history (mid/late-90s; see Explanatory Note i), there was a strong negative connotation associated with Five-Year Plans. And to be fair, at that time, there were many good reasons to be skeptical about Five-Year Plans. After all the first few cycles ranged from mediocre to disastrous and it was still too early to really judge the long-term effects of plans conceived under the watch of Deng Xiaoping — too early to be reflected in the mainstream thinking of the day, and certainly too early to be reflected in the few paragraphs (if that) dedicated to modern Chinese history in the high school history textbooks where I had gained my first exposure.

Five-Year Plans were also tied to the idea of central planning, an economic concept that was being thoroughly discredited in real-time with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the break-up of the Soviet Union and what many expected to be the eventual fall of Communist China, as symbolized and captured by those fateful spring days in Tiananmen in 1989.

With the benefit of the last three decades of hindsight, by now we all know that China did not follow the path of the former Soviet Union. This reality demands that we re-assess the concept of a Five-Year Plan, because it is a very important part of understanding the China of today.

Can China reform inefficient state-owned enterprises (SOEs)?

Here I discussed the history of how Chinese policymakers had reformed the famously inefficient state-owned industrial sector, which began in the 1980s alongside the higher-priority agricultural reforms but really only being pushed in earnest in the early 1990s.

One of the key takeaways of the answer is that there appears to be a “playbook” that modern Chinese policymakers follow when implementing economic reform:

Strategize — identification of the priority issues and discussion and brainstorming of various approaches to address those issues

Plan — drawing up specific policy and laws

Experiment — allow a wide variety of creative ideas to be implemented in a controlled manner

Assess — use real-time data from the field to evaluate which ideas are working the best out in the real world

Mass Implementation — choose the best ideas and roll out en masse across the country

The timetable for this playbook is often — but not always — tied to a five- or ten-year planning cycle. For instance, as the Five-year Plan sets out the high-level objectives, the first year may be tied to coming up with ideas on how to implement these objectives, the second year may be for drawing up specific legislation, the third year for selective experimentation and the fourth and fifth years for mass roll-out.

In other words, this five-year period sets the cadence of most reform programs today, and reforms typically follow the structure I outlined above.

We can see how this “playbook” has been implemented by looking at past reforms.

For example, when China looked to open up to the world and implement certain free market-oriented policies, they set up Special Economic Zones (SEZs) that had special treatment and followed different sets of rules from the rest of the country. Four coastal cities were designated as SEZs as well as the entire island province of Hainan.

The interesting thing is that for the most part, out of the original four, only Shenzhen became an export powerhouse. Nevertheless, by the early 1990s, this was enough validation and ammunition for Deng Xiaoping to make these reforms permanent with one of his last acts as China’s official leader, the Southern Tour in 1992. The lessons learned from Shenzhen were subsequently rolled out broadly to other cities in China.

The SEZ example illustrates an important concept — the competitive rivalry between Chinese cities and provinces in implementing economic reforms. Often times cities or provinces are used as controlled experiments, pitted against each other to see who can do the best job competing for investment capital, talent, etc. It is not unlike the process Amazon recently ran to select its second global headquarters.

Perhaps the most important — and possibly least well-understood — phases of the playbook are the “Experimentation” and “Assessment” phases.

During the Experimentation phase, sometimes there are a lot of crazy ideas that are considered. This does not mean that they will all be implemented at the national level, but still I often see some of the fringe ideas hyperbolized or otherwise blown out of proportion as if they represents a mainstream trend line. This is also not just limited to “Western Media” but Chinese-language media as well in Mainland China and throughout the region. A good example is how “Social Credit” — which is clearly in the middle of its “Experimentation” phase — is being covered i.e. all of the dark Orwellian and Black Mirror references.

During the Assessment phase, there is typically some sort of pause in the experimentation whereby some of the wackier ideas are discarded or thrown out but also where even the good ideas are temporarily halted. The problem I see is that this scheduled “time-out” is often viewed as a reversal in the reform program.

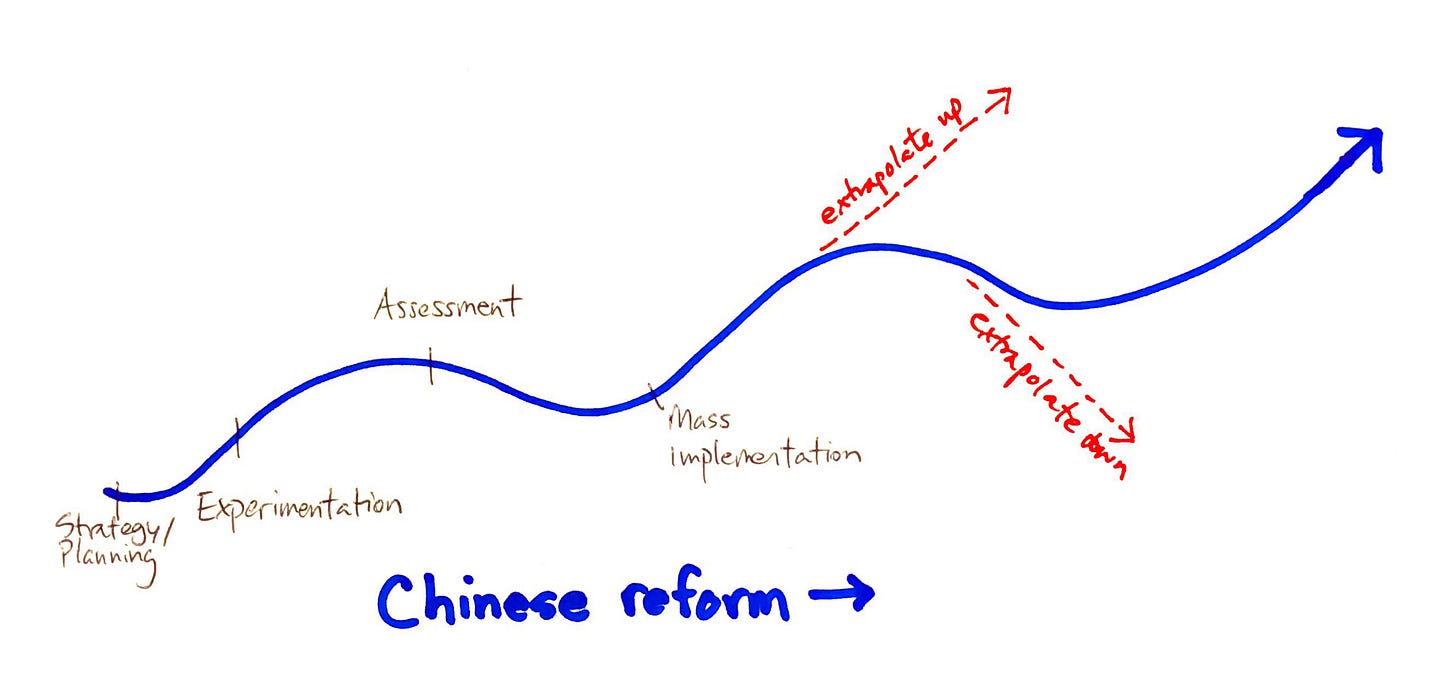

The problem is that Chinese and non-Chinese alike have a tendency to extrapolate based on whatever the most recent trend line is instead of considering this cadence that I am talking about. One well-known cognitive bias called “recency bias” provides a partial explanation for this phenomenon. The graphic below illustrates what I am talking about:

As the experimentation phase begins, you see a flurry of change in the Chinese economy. Entrepreneurs rush in (see: dockless bike-sharing circa 2016), new entrants feel emboldened to compete against incumbents (see: Ant Financial circa 2016), incumbents expand horizontally into new areas (see: SOE interest rate arbitrage). Capital, of both the human and financial varieties, is drawn into new endeavors. It is a period of great change and activity.

After a while, this whirlwind of activity and growth becomes the status quo. Some mistakenly assume that the slope of the trend line has made a permanent shift higher and extrapolate this trend line far into the future. This is how bubbles are blown in the economy, which leads to the inevitable bad behavior and declining marginal benefits. And many experimental ideas are simply bad.

This results in policymakers calling “time out”, followed by a phase where they are assessing the results to see which ideas hold water and which should be thrown away. To those on the outside, it may look like a step back in the reform program. Those that had over-extended themselves, thinking “good times would last forever” are now beginning to really worry whether their business is going to survive.

Economic growth reverses and fear rises. Companies lay off workers, preparing for a “nuclear winter”. Stock markets and the real economy stumble. After a while, people assume that now the “bad times will last forever”.

The fundamental mistake people are making is misinterpreting a cyclical trend for a secular trend. This is a common problem I have come across in many investing disciplines as well.

Knowing the cadence of Chinese economic reform can help you recognize whether something is cyclical or secular by providing you a sort of process roadmap. It may help you dig beyond the simple narratives that often get a disproportionate airtime in the headlines.

Let me explain what I mean by this by taking a deep dive into interest rate liberalization.

Keep in mind that interest rate liberalization is just one sub-category within a broader set of financial reforms, which includes things like equity capital markets, the insurance space, exchange rates, financial technology etc.

In mature financial markets, interest rates are typically used to reflect the financial risk of the underlying asset. For example, a relatively low-risk mortgage secured against an apartment by a highly qualified borrower may feature interest rates in the 3 to 5% range while a bond collateralized by the cashflows of a highly leveraged buyout could be as high as 8 to 10%. The higher interest rates reflect the higher risk of the borrower, the assets it is secured against, and/or the underlying rights of the debt instrument to protect itself.

Until about 6–7 years ago, China’s financial system was still very simple by modern standards. You really had a few financing options: debt in the form of loans or informal lending and equity from scarce savings pooled together from family and friends or FDI. If you wanted to get a loan from the bank, you pretty much had to either be a state-owned enterprise or own a hard asset like real estate. There was a narrow band of interest rates at which you could borrow — interest rates weren’t really used as a tool to price risk. Underwriting was a yes/no decision.

This simple system worked fine for the first two or three decades of economic reforms. China’s economy was very inefficient and capital was scarce, which meant tons of “low-hanging fruit” opportunities to deploy capital. The ability to gather and deploy capital was far more important than discerning the relative attractiveness of projects (and expressing the risk/reward in the form of differentiated interest rates). Every sector of China’s economy needed capital. Sophisticated financial innovation was not necessary to match savings to investment opportunities.

However, as the mid-2000s rolled around, China was no longer capital-starved and a lot of the “low-hanging fruit” investment opportunities had been picked. The question of how to further deploy capital in a more sophisticated manner became increasingly important. Certain sectors, with access to cheap capital, were starting to over-heat. The problems from rising corruption within SOEs was amplified by access to nearly unlimited, subsidized funding. This was reflected in various return on capital metrics within the broad SOE sector.

By 2012, the systemic risk for inefficient of capital had reached an elevated state. SOEs had been borrowing at near-zero real interest rates for the better part of the last decade. Chinese policymakers realized that time was overdue for major financial sector reforms. It was not a surprise then that financial reforms (including interest rate liberalization) featured heavily at the November 2013 Third Plenum announcing the major policy initiatives for the new Xi Jinping administration.

Policymakers encouraged the rise of “shadow banking” as an alternative way to funnel capital to the private sector at a wider range of interest rates, particularly in the real estate sector.

As the state-owned banks had never had to really learn how to underwrite much private sector credit, policymakers decided that new industry players would have to take on this role. State-owned banks would offer new products such as wealth management products (similar to certificates of deposit) to their retail customers and these funds would be pooled together and lent out at typically higher rates.

New intermediary institutions arose to take on the relatively new responsibility of underwriting and pricing risk. SOEs also got involved, leveraging their access to cheap bank loans to make easy profits by re-lending at higher rates to the private sector or even other less creditworthy SOEs. Completely novel approaches such as peer-to-peer lending also arose. From 2013 to 2016, the collective “shadow banking” sector grew rapidly.

However, as we have seen elsewhere, too much of a good thing can lead to excess, which is bad. Immature institutions were still learning how to assess and underwrite risk. As these new capital sources flooded the economy, bad behavior and excess grew. In 2017, policymakers began reining in credit, especially in the relatively immature “shadow banking” sector — which had a disproportionate impact on private real estate development.

This credit tightening cycle has crimped growth in the private sector. This slowdown started to become evident in 2018, several months before the U.S.-China trade dispute began to escalate. This was reflected in China’s capital markets, which began to pull back before the summer and today still sit in bear market territory. Thus far, the economic impact of increased tariffs has actually been quite low, as evidenced by an actual increase in China’s trade surplus.

The critical question here is whether this tight liquidity situation will continue. In other words, is this a secular trend or a cyclical trend?

Understanding where policymakers are in the reform cycle lends some perspective to this question:

From 2013 to 2015, policymakers agreed that interest rate liberalization was important and starting drafting plans and regulations.

In 2016 and 2017, China was in the “Experiment” phase. This is when there was an explosion of new credit products, peer-to-peer lending, new entrants in the market, etc.

In mid-2017, policymakers hit the “pause” button and entered the “Assessment” phase. Policymakers are in the process of trying to figure out which policies worked well, which industry participants demonstrated competence, etc.

The implication of this view implies that they will at some point push the “play” button and enter last phase, “Mass Implementation”. This time, there will be a clear set of more-or-less permanent policy initiatives to implement interest rate liberalization. The best ideas coming out of the “Experiment” phase will be kept and widely implemented.

In other words, the tight liquidity situation for private companies will at some point abate.

Of course, this is just one view and could be wrong. An alternative view I have heard is that China does not have any additional credit capacity and was essentially forced to tighten in order to avoid systemic risk associated with too much debt. I just do not think the facts support this view.

Based on my read of the situation, analysis of the “real” credit situation and understanding of the cadence and cycle of Chinese reform, I think it is far more likely that the Chinese economy is at the cyclical bottom as it relates to interest rate liberalization. This is not a permanent thing.

As policymakers move into “Mass Implementation” phase, credit will flow again to the private sector, and the players responsible for making underwriting decisions will have improved from the experimentation phase.

It will be interesting to see how things play out over the next year to see which view is ultimately correct.

To summarize, here are some of the key takeaways:

Development in China has often been a “Two steps forward, One step back” process. People often make the mistake of thinking the “One step back” piece is a permanent directional shift.

Sometimes you see some extreme, weird or wacky things going on in China. One should keep in mind that the more extreme elements may actually be controlled experiments that are not likely to be rolled out en masse.

China’s economy actually becomes a lot more predictable if you take the time to read its publicly available Five-Year plans. They really do provide a decent roadmap for thinking about development in the medium- to long-term. For example, financial reforms (including interest rate liberalization) are discussed in Chapter 16 here.

Understanding where a specific policy initiative is in the reform cycle helps you analyze the situation better at the micro-level.

Chinese policymakers often use cities and provinces as controlled experiments competing with each other on different approaches to implement policy. These experiments feed valuable data which is used to assess the viability of certain approaches for nationwide rollout.

Understanding the cadence of reform doesn’t mean you will know exactly how things will turn out. After all, the policymakers themselves are actively experimenting to see which policies work better than others. Sometimes they succeed, other times they fail and reforms are kicked down the road to the next Five-Year plan.

With interest rate liberalization the secular trend is reaching the long-term goal of a more sophisticated financial sector that can underwrite credit risk more finely than before (through a wider variety of financial products geared towards different type sales of risk). The cyclical trend points to China being in the “Assessment” phase and looking to eventually transition to the “Mass Implementation” phase in the near- to medium-term.

Explanatory Note

[Note i] My first material exposure to modern Chinese history (outside of hearing stories and anecdotes from relatives, mostly about wartime China during World War II) was probably in my World History AP class that I took in high school. There may have been at most a few paragraphs dedicated to the topic of modern China in the textbook. I may have also done more in-depth reading into the topic on my own.

My first college-level study on Chinese history was AMES 089 “China in the 20th Century” which I took my last semester of senior year in college, taught by Professor Arthur Waldron.

This was originally published on Quora in January 2019.