Last week, I started looking closely at the local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) that sit at the heart of many of the current economic concerns in the Chinese economy. Over the week, I continued my deep dive in a series of follow-up tweet threads1 on Twitter. I would like to synthesize, incorporate some of the feedback I have received, and expand on some of the key points here and a series of future posts.

Unlike much mainstream commentary on LGFVs, which tends to focus on the debt and liabilities side of the balance sheet, I have focused primarily on the assets. As I wrote last week, “LGFVs are asset-backed structures with revenue-generating or liquidatable assets to service and support the debt.” Focusing on a LGFV’s debt without considering its assets is like judging a piece of art based on how much it cost. LGFVs come in all different shapes and sizes and getting a handle on them requires some digging.

For this post, I will walk through the various categories of LGFVs that I have come across in my investigation:

The Infrastructure LGFV

The Real Estate Asset Management LGFV

The Structured Asset-Backed Warehousing LGFV

The Financial Intermediary and Investment Holding LGFV

The Conglomerate “All-of-the-Above” LGFV

LGFVs come in a variety of flavors

Assets held or controlled by local governments2 can be traced back to the major reforms (抓大放小) of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the 1990s. The first LGFV was established in Shanghai in 1991. Out of these reforms, the larger assets were retained under the direct administration of the central government while the remaining assets were “let go” to be privatized or restructured.

So if the central government got the large assets, what was leftover for local governments? There were some interesting assets, like regional liquor companies … but ultimately the biggest was land.

For the last two decades — and especially since the 2008 global financial crisis when LGFVs were used to deploy China’s ¥4 trillion stimulus package — the primary role of local and provincial governments has been to develop this land. The vast majority of assets created and sitting on LGFV balance sheets have something to do with the development of this land.

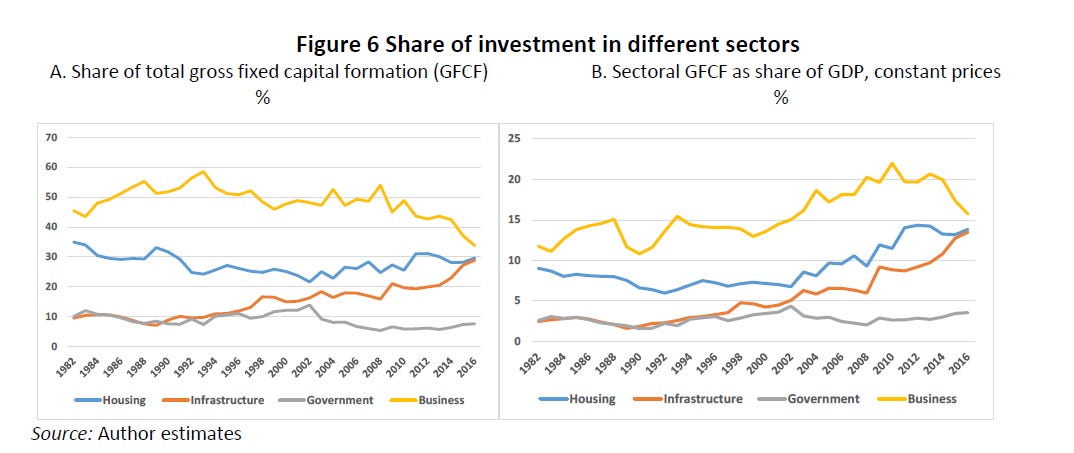

These charts show the share of investment3 in several major asset categories (housing, infrastructure, government and business) over time and are useful in framing an asset-centric discussion and analysis. As you can see clearly here, the rise in investment as a percentage of GDP since the 2007-08 GFC has been driven almost entirely by housing and infrastructure investment.

Housing, infrastructure and business capital stock represent three very different asset classes. Each has its own unique characteristics and different metrics to measure efficiency that can be lost by analyzing investment on an aggregate basis. Even within each of these asset classes, there are additional sub-categories of assets and sub-sub-categories … this next-level analysis is critically important.

Let’s get to know some of the various forms of assets held by LGFVs.

(1) The Infrastructure LGFV

Last week, we discussed the role that local and provincial governments played in the development of infrastructure by discussing a major high-speed rail (HSR) project in Southwest China, the GuiGuang High-Speed Railway.

For most HSR projects, the local or provincial government’s main role was to secure land for the HSR track and new stations. China Railway, the central government SOE, would be responsible for coordinating the actual construction using a standardized, nationwide process. Some of the construction work might be sub-contracted to local construction firms that were subsidiaries of LGFVs.

After the railway was completed, LGFVs would be responsible for maintaining HSR track located in their region and other related operations including real estate operations at the stations and local advertising. Real estate related to HSR projects was often very successful (and valuable) because train stations naturally attracted significant foot traffic, which is a key driver of real estate returns4. These operations would become a main source of revenue that could cover operational costs and service its associated debt.

Other types of infrastructure would follow a similar formula with varying degrees of involvement from central government entities. For highways and expressways, this was largely executed at a local or regional level with less involvement from the central government. They would have their own sources of revenue (tolls for expressways, usage fees for airports, etc.) to cover operations and service associated debt.

(2) The Real Estate Asset Management LGFV

Local governments played the principal role in developing land to support national urbanization and poverty alleviation goals. This included coordinating and facilitating the development of industrial parks, tourism venues, government facilities etc.

These types of LGFVs sat at the heart of many of the infamous “ghost cities” e.g. Zhengdong New District in Zhengzhou, which was featured on 60 Minutes in 2013. Zhengdong has been one of the more successful ones, driven by a relatively strong local economy. At least 1.4 million people have moved in and “more are on the way”.

Often, LGFVs would retain significant real estate assets “on the balance sheet” that would generate revenue in a variety of ways. Given the long-term nature of some of these new planning districts, the payback periods could be very long. The long-term success of these new planning districts ultimately rested on their abilities to catalyze economic development.

And not everyone was as successful as Zhengdong.

(3) The Structured Asset-Backed Warehousing LGFV

Local governments also played a principal role in developing land for residential housing and commercial projects. However, here they would not aim to retain assets “on the balance sheet” after they were built.

Instead, they would partner with private developers such as Evergrande to develop and market the properties, with the goal of ultimately liquidating by selling to households or private commercial property owners.

From this perspective, LGFVs could be viewed as temporary warehousing facilities. However, in China’s relatively unsophisticated banking system, there was little formal differentiation between different types of assets. Contrast this with modern financial systems, where your options to structure and manage asset-backed warehousing facilities can be quite different from your options for assets that you intend to keep on the balance sheet.

It is somewhat analogous to the business of structuring and selling collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) vs. the business of setting up and managing real estate investment trusts (REITs). “CDOs with Chinese Characteristics”, if you will.

With these types of structures, the critical success factor is asset turnover: How quickly can you secure the land, develop the property and sell the individual units? The shorter the cycle, the more capital that can be put to work into the real economy.

But as with CDOs during the Sub-prime crisis, it is like a game of musical chairs. When the music stops (i.e. the liquidity ends), capital is stuck within these entities. This is what happened to Evergrande and other real estate developers in August 2020 when China introduced regulatory guidelines to rein in the property-development sector. The music stopped, and a year later, Evergrande began running into liquidity issues.

And for LGFVs, this also means that the capital they had tied up would take longer to be recycled and redeployed for other purposes. Indeed, since private sector real estate developers started running into a liquidity crunch in 2021, LGFVs filled the liquidity gap by taking up 30-40% of commodity residential land supply in Tier I and II cities (up from <10% previously)5.

Acquiring and developing land is very capital-intensive and many LGFVs themselves have run out of money and/or borrowing capacity. So far the central government has not stepped in a big way to help with liquidity (we will discuss in a future post the reasons why).

(4) The Financial Intermediary and Investment Holding LGFV

In addition to the long-term assets, many LGFVs also sit on a ton of liquid assets like cash and short-term deposits. These need to be managed and typically this is done within the treasury department of large corporations.

LGFVs also differ in credit quality and rating, allowing some to borrow greater amounts at lower rates. This led to much “inter-LGFV” lending and borrowing as well as lending to the private sector where it was generally more difficult or more expensive to borrow from the formal banking sector.

In addition, LGFVs often would invest in other LGFVs or private sector companies. For example, they might band together and form a syndicate to invest in a regional project alongside others that (may or may not have) had a vested interest in the project.

If we imagine LGFVs as one large related conglomerate, like a Korean chaebol or Japanese keiretsu, this would be akin to the inter-company lending and borrowing operations between different conglomerate subsidiaries or equity cross-holdings with sibling companies.

While these informal financing operations made sense when the economy was poor and formal institutions relatively weak, it is not a particularly efficient way of managing capital flows — finance departments at LGFVs had little or no experience making underwriting decisions and there were few established standards over the process.

This phenomenon was again driven by the relatively unsophiscated and conservative nature of the Chinese financial system. Because the formal banking system took such a “one-size-fits-all” approach to lending, it gave the entrepreneurial local officials of the “mayor economy” reasons to find loopholes.

As often occurs with unregulated financial activity, it also led to poor decision-making, excess and impaired assets in many cases. For Japanese and Korean conglomerates, this informal financial intermediary role began to run into problems in the 1980s and 1990s, respectively, and it became increasingly difficult for these conglomerates to maintain acceptable capital efficiency levels.

(5) The Conglomerate “All-of-the-Above” LGFV

The reality is that most LGFVs were “All-of-the-Above” holding infrastructure assets, real estate assets, operating businesses, minority investments in other enterprises, etc.

In last week’s post I referenced Zunyi Road & Bridge Construction Group (遵义道桥建设) which in January had agreed with creditor banks to extend maturities and modify interest rates on about $2 billion in outstanding loans.

Despite its name, Zunyi Road & Bridge Construction Group (“Zunyi LGFV”) was much more than just roads, bridges, and construction operations. Fellow Substack writer David Fishman at Crossing the River by Feeling the Stones looked into Zunyi LGFV and here is a sample of assets from the $27 billion behemoth:

Agricultural Expo Park (遵义道桥农业博览园有限公司): a local tourist attraction in Zunyi’s suburbs located near the airport.

Hotels (遵义道桥酒店管理有限公司): a group of hotel developments

New Planning District holding company (遵义市新区建设有限公司):

Everything from commercial real estate to logistics, street sweeping and ecological management. An LGFV within an LGFV.

An investment holding subsidiary with a media company, public bikeshare, software investment park, airport expressway, a 49% stake in a Sinopec new energy venture and more.

Another investment holding subsidiary with minority stakes in a random mierda6 including a car rental company, titanium interest etc.

Thankfully, it also owns an actual bridge (遵义潘州路桥有限公司) and does construction (遵义房地产开发有限公司).

LGFVs were often set up by cities to facilitate investments within that administrative unit. As you may have guessed, Zunyi LGFV was established as one of the main entities holding major developments in a city called Zunyi (遵义).

Nestled in the hills of northern Guizhou, Zunyi is a prefecture-level city that sits between Guiyang, the provincial capital, to the south and Chongqing to the north. With an official population of 6.7 million, its actual urban population is 2.4 million (density of 1,800 per sq. km), putting it very roughly on par with the city of Houston (2.3 million at 1,400 per sq. km).

There was a wide range in the competencies of local officials managing these municipal-level LGFVs. Some of them were strong. Others were weak. And others were pure mierda. In follow-up posts, I will present frameworks that we can use to figure out which category certain LGFVs belonged in.

Including those not included in local government financing vehicles

Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF) comprises the vast majority of Gross Capital Formation, a.k.a. “Investment”. It includes the formation of fixed assets buy excludes changes in working capital such as inventory.

Many analysts often exclude ancillary “non-transport” revenue sources like commercial rent and advertising from their evaluation of HSR investment. But as I outlined here, this is a crucial part of the passenger rail model that provides a significant portion of its profitability or can effectively subsidize ticket prices.

UBS “China Banks: Is LGFV debt a potential drag on bank earnings & capital?” (May 29th, 2023)

David used a different word here but I am trying to keep this family friendly.