The World's Largest Economy in 2100

If China surpasses the USA, who is most likely to surpass China in the future?

I am going to go with the United States, re-capturing the “largest economy” title sometime in the late 21st / early 22nd century. Note: Standard caveats about long-term forecasting apply (e.g. that it is nigh impossible).

Let’s try to keep things as simple as possible by boiling it down to the two variables that really matter:

Population — the easiest to forecast over a long period of time. As they say, “demographics are destiny”.

Productivity — as measured by per capita GDP in relative as opposed to absolute terms.

The obvious contenders for the title of largest economy by the end of the the 21st century are China, the United States and India.

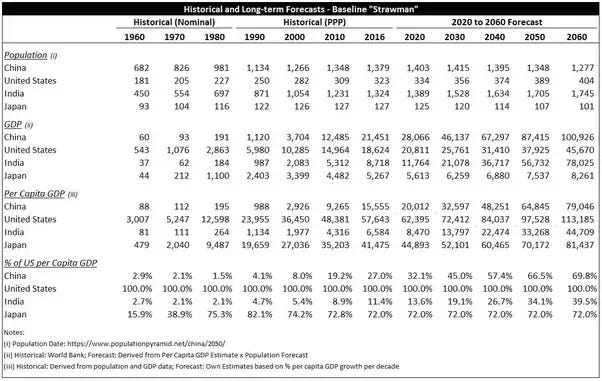

Here was my first stab at forecasting GDP over the next half-century:

Keep in mind that this is really just a strawman to kick off the conversation. These assumptions could — indeed, are almost guaranteed to — turn out to be quite off.

I do not want to get stuck on this table but instead use it to set up a mental framework on how to think about these assumptions and what they ultimately imply in terms of the “big picture” questions.

From there I will look at alternative scenarios that show how the U.S. can re-capture the title or how India could rise to the top.

Variable 1: Population

Let’s start with the easier variable because we have a pretty good idea of what population looks like … at least for the next two or three decades.

China’s population is expected to peak in the late 2020s and then start to gradually decline while the U.S. population is expected to grow albeit at decreasing rates. Meanwhile, India’s population is not expected to peak until around 2070 at close to 1.8 billion.

“Demographics is destiny” holds true for the next two decades but afterwards population begins to increasingly depend on things like birth rates, life expectancy and immigration policy over this period of time.

For example, China recently relaxed its notorious “One-Child Policy” to a “Two-Child Policy”. While this will have very little tangible effect on population forecasts for the next two decades, it could have a large effect on the population forecast in 2060. Case in point: Apparently, there has been a mini-baby boom since the relaxation of the “One-Child Policy”.

For the United States, the population forecast depends largely on our immigration policy. The U.S. has seen population growth spurts several times throughout its history. There was the big European immigration wave in the late 19th century and then the post-1960s wave from non-European countries. Although right now it feels more like there is a backlash against such open immigration policies.

Meanwhile, India is almost guaranteed to have the largest population sometime in the next decade. But what will the population ultimately peak at? As I’ll delve into below, for India more than the other two, there is a major question as to how supporting such a large population will affect economic development itself.

Variable 2: Relative Productivity

For very long-term projections, I think about relative productivity — measured as the per capita GDP ratio between two economies. In today’s economy, the benchmark is the United States and contenders are analyzed as “catching up” to the U.S.

On this measure, the average Chinese person in 2016 was 27% as productive as the average American. This leads to the key question for China: what is the ceiling for this number? Can the average Chinese person be 40% as productive? 65%? 120%?

This is of course a very difficult question to answer. But we can look back towards history to give us some perspective. I included Japan on the table because we can see how at its peak Japan got to around 82% of U.S. per capita GDP and is currently sitting at around 72%. So one can ask questions like “Can the average Chinese person can be as productive as the average Japanese person?” If so, given current population projections, China’s economy is still likely to be larger than the U.S. by the end of the 21st century.

We can also flip this around think about it from the opposite angle. For example, asking the question “What level would China need to hit in order for the U.S. to catch up by 2060?” Now it becomes just simple math. China’s population is forecast to be 3.2x larger, so if economic development hits some sort of ceiling at 32% of U.S. per capita GDP then that means the U.S. may very well pull ahead of China on the basis of improved demographics.

India is the real wildcard here. Economically, it is the hardest to project because it is starting at the lowest level of development out of the three. We can apply the same simple math to India (but instead compared to China) to see what percentage per capita GDP it needs to hit in order to pull ahead. In 2060, India’s population is forecast to be 37% higher than China’s, which implies that all it needs to achieve is 73% of China’s per capita GDP to pull ahead.

Now that we have established a mental framework, let’s try to boil this down into some critical real-world questions that will determine each economy’s prospects for holding the title of “world’s largest economy” by the end of this century.

Contender #1: China

China’s critical questions revolve around how far it can ultimately go with economic development. A secondary question has to do with population policy but that will be less important.

What is the ceiling for Chinese productivity?

35% of the U.S. (countries like Argentina and Uruguay today)?

70% (countries like Japan and South Korea)? Even higher?

Will Chinese policy changes today lead to a stabilization of population in 2040 and beyond?

Example of the mini-baby boom going on following relaxation of the One-Child Policy — could have significant ramifications on population projections two decades from now.

China has higher forecast risk than the U.S. (but lower than India) because it is still scaling the economic development ladder but it looks quite likely at this point that it is fully breaking out of the “middle income trap”. Fairly conservative forecasts predict China will become a “high income” economy within the next five to six years.

China probably holds the title for quite some time until long-term demographics reduces the population gap with the United States.

Contender #2: India

India’s critical questions revolve around the interplay between population and economic development:

Will India be able to manage 1.7+ billion people?

How does India solve basic questions about food security, pollution and natural resources?

At what point does over-population impair the ability to develop economically?

Will India be able to break out of the “middle income trap”?

India’s prospects clearly revolve around its economic development. While it is very clear that India will have the largest population quite soon, because its economic development is well behind even China, there is significantly higher risk on this measure.

It is by no means pre-destined that India will become a fully developed country and the strain caused by over-population (pollution, coordination etc.) just makes the development problem harder.

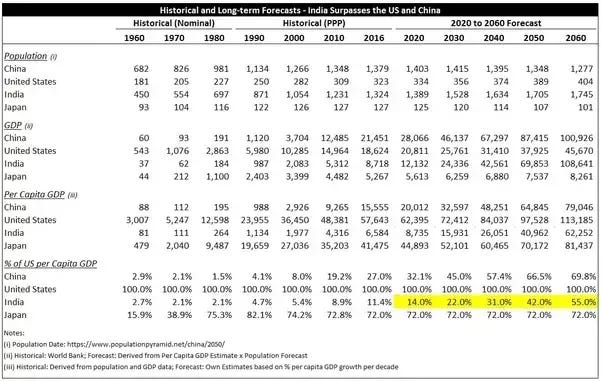

But if India is indeed able to break out of the “middle income trap”, it will be a strong contender to challenge China in the second half of the 21st century. Here’s what that might look like in a scenario where India reaches 55% of US per capita GDP (from 11% today):

Contender #3: United States

I ultimately chose the United States because I think it has the lowest forecast risk out of the three:

We are the most secure economically with an already welathy economy and highly educated population.

We are the most well-defended with the world’s leading military, two wide oceans protecting us from potential enemies and natural allies surrounding us.

Population-wise, we have the most arable land which I presume will still be quite important a century from now. Based on this, we can support a population several times higher and still maintain a high quality of life. It’s really just a matter of our collective choice to do so — primarily through our immigration policy.

Really our job is to just avoid “screwing up” whereas China and especially India have their work cut out just to catch up.

So out of the three, I am about as confident as one can be when making any such long-term forecast that the United States will be one of the wealthiest and most productive economies in the world a century from now. As such, the one critical question just has to do with what our immigration policy looks like going forward.

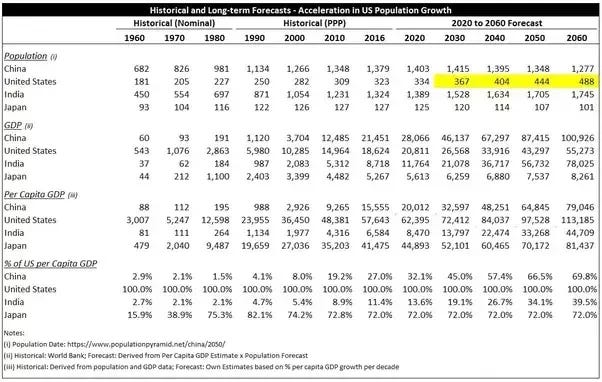

If we increase the rate of population growth in the long-term forecast to around 10% per decade (which is well below historical rates e.g. the 70s or 80s), by 2060 we would be rapidly closing the gap with China and on track to regain the title by the end of the century.

Here’s what that scenario looks like:

This was originally published on Quora on January 4th, 2018.