Why is China so good at building HSR compared to the U.S.?

Economic comparative advantage

Building high-speed rail networks is more about coordination than any sort of underlying technology issues:

The software and signaling systems used to coordinate hundreds of trains in a rail network are less sophisticated than systems used to coordinate the thousands of planes that are flying in the air at any given moment.

The technology to accelerate a passenger train using electricity to over 200 mph has been around for a long time. But to do it safely means building very straight tracks with wide curve radii.

The largest cost item in most high-speed rail projects is a result of the need to cut these straight lines through populated areas. Reducing land acquisition costs is all about coordination with local communities along the right-of-way.

Providing a good transit experience for commuters is about reducing intermodal friction costs. In other words, making the hand-off from long-haul inter-city rail to local transit networks (bus, subway, auto) as seamless as possible. Once again, this involves coordination between state and local officials.

Thus, the decision to invest a massive amount of effort and coordinate resources is really a question of economics: Do the incremental economic benefits of going through this coordination exercise outweigh the costs? And to put it bluntly, the economics of high-speed rail work in China and they don’t work as well in the U.S.

This could change in the future with technology advancements in related areas (e.g. autonomous vehicle technology, proliferation of electric vehicles) but under the current situation, this is the reality that prevails.

In the United States, it costs a lot to build high-speed rail:

It is expensive and time-consuming to acquire land — that is the price you pay for strong property rights.

Construction costs are high — that’s the price you pay for being an advanced economy with developed safety laws and regulations.

Topography may also play a role, depending on the region.

Cost is not just about money, it is time as well. Authorities are projecting Phase I of the California HSR project to be completed in 2033. Because it takes so long to complete, you have to contend with the double-whammy of delaying the benefits well into the future while dealing with living next to a construction zone for many, many years.

Assuming you can overcome these obstacles and get the rail network built, you then need to contend with the risk of low capacity utilization or ridership:

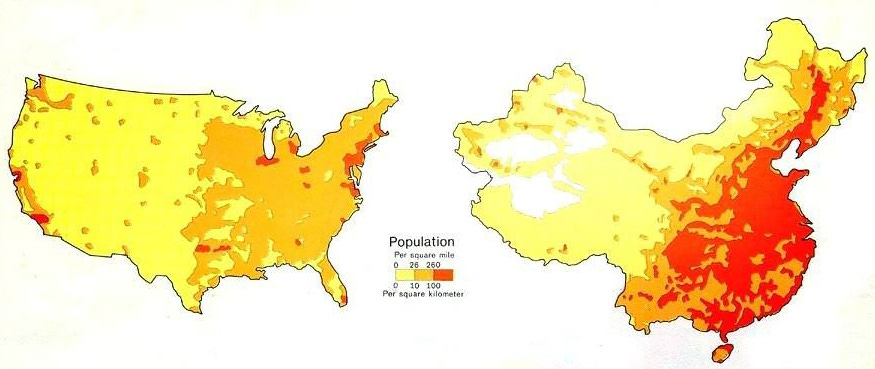

Population density is relatively low and even in developed areas, families seem to favor living in low-density “suburban sprawl” type development. Train station design is very different in high-density vs. low-density environments. For example, the amount of space dedicated to parking is significantly higher in suburban environments vs. urban environments.

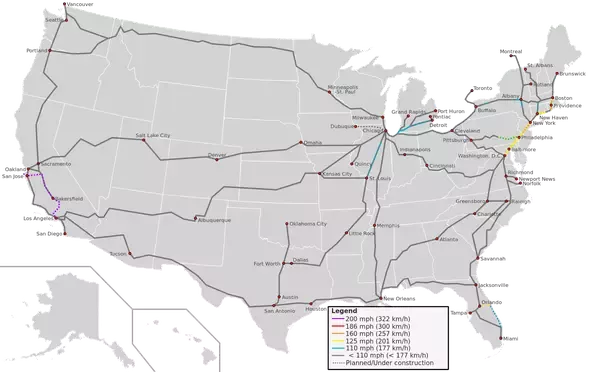

The most heavily trafficked and populated corridors in the U.S. are point-to-point vs. web-like networks. Think San Francisco to Los Angeles or Boston to Washington, D.C. Furthermore, the heavily populated coastal regions are separated from each other by thousands of miles of relatively sparsely populated interior. The time savings of high-speed rail tend to get overtaken by air travel around the 400 to 500-mile mark — this is why it doesn’t make much sense to build high-speed rail in Australia either.

Transportation alternatives are well-developed. The incremental time and convenience benefit of HSR in many situations is not that much better than the alternative.

Some of these factors can be solved by time and technology advancement. For example, construction techniques may improve so that it becomes easier to lay track. The country has strong demographics and robust inbound immigration and population density is rising faster than other advanced economies.

But some things are structural in nature: Strong property rights and labor laws are good characteristics that should not be materially changed, in my view.

In China, it is inexpensive to build high-speed rail:

Land acquisition is easy under China’s authoritarian system. In China, land is ultimately owned by the State and individuals only own “land use rights”. For everyday situations, this is not unlike property ownership but if the government needs your land, you have fewer protections — you may get some form of compensation but probably nothing compared to what you would get if you owned the property outright. Your ability to hold up the process will be limited.

Construction costs are low — China has a large blue-collar labor pool and can leverage economies of scale — like a massive beam-launching machine that was invented for the sole purpose of laying high-speed rail track.

Topography is fairly mild in the places Chinese people have historically tended to congregate and live. This means fewer expensive bridges and tunnels that need to be built (even then, China has still had to build a massive number of these).

China can move fast. In the time it is projected to build out the 800-km line from San Francisco to Los Angeles, China is planning to complete an entire “8x8” high-speed rail network totaling over 30,000 kilometers that connects nearly every major Chinese city to the grid. Typical lines are completed and operational within 4–5 years of initial planning. In other words, Chinese are able to realize the economic benefits of their construction efforts much, much sooner.

Once Chinese high-speed rail lines were built, they were heavily utilized:

Population density is high, especially if you exclude two-thirds of the country out west in areas that are mostly desert and mountains and thus, sparsely populated.

Chinese urban development tended to develop in a more web-like design. Web-like rail networks tend to be used more intensively, as it allows for incremental transit traffic to supplement traditional point-to-point traffic. For example, as you can see (if you squint) in the map below, Changsha has become a major transit center as it carries both North-South traffic (Guangzhou to Wuhan) and East-West traffic (to Shanghai).

Transportation alternatives are less well-developed in still-developing China. For one, fewer people own their own cars. Fewer people can afford air travel. So the cost-value proposition of high-speed rail over the closest long-haul options (e.g. bus, regular trains) is superior in many cases.

Intermodal friction costs are lower in China. In almost every instance, high-speed rail, local metro and local bus stations are all in the same place. I will note the huge contrast in my first experience taking a Chinese high-speed train and switching to the subway in Nanjing with the experience I have trying to transfer from the NYC Subway to the Airtrain to John F. Kennedy Airport.

Since high-speed rail made economic sense in China — which we are starting to see in the financials of the main company involved in running these networks — it made sense to build a lot of high-speed rail lines and absorb all of the related technologies and know-how that are required to implement it efficiently. People and companies learn through repetition and so it should be entirely unsurprising that Chinese firms developed core capabilities in building and implementing high-speed rail networks.

The net result of these structural differences is that usage of passenger rail (all types, including non-HSR) in China is around 21x that of the United States (1,346 billion passenger-km compared to 63 billion). Adjusting for population, use of passenger rail is still 5x more prevalent.

I would love to see high-speed rail happen in the U.S. but it has to make economic sense. We have to remember that resources are limited, and allocating resources to one area has an opportunity cost.

For example, perhaps a better use of economic resources is figuring out autonomous driving technology or taking the lead on electric vehicle technology — both of which could solve some of the issues of low-density suburban sprawl.

Perhaps once we solve autonomous driving and/or shift to a more sustainable energy strategy (solar/battery + electric vehicles), the economics of high-speed rail change such that it becomes an attractive option at that point.

And maybe it is not even technology-related change that impacts the economics of high-speed rail. For example, there seems to be a growing trend to live in walkable (i.e. “higher density”) neighborhoods instead of traditional “suburban sprawl” type environments. But these changes happen gradually and take many decades to really play out.

Once the economics of high-speed rail make sense where we can deploy high-speed rail networks at scale, figuring out how to build it will be easy. The underlying technology isn’t rocket science. I have faith we can figure it out out after a few reps.

So just because high-speed rail doesn’t make economic sense today does not mean that it won’t in the future.

This was originally published on Quora in December 2018.