How widespread is “data inflation” in Chinese economic statistics?

Varies between national and local

Caixin Global: Tianjin Economic Zone Cuts 2016 GDP Figure to $102.3 Billion

Data collection bias is widespread at the local and provincial level and less so at the national level. This is due primarily to the role that incentives play in determining career success for government officials and administrators. The discrepancy is also from separate data collection and analysis processes at the national vs. local levels. I hesitate to use the word “inflation” because it implies a single direction; in many cases, data bias is actually “deflation” — it really just depends on what the incentive is.

In a previous answer, I discussed a case where there was clear data collection bias for local population growth data and how it was very likely caused by incentives:

Most people know that one of the major policy goals for China during the 1980s was to reduce the population growth rate; hence, the famous One-Child policy etc. The researchers in the above paper found moderate correlation between success in lowering the population growth rate and promotions of local officials. The problem was that once you double-checked the locally reported data with the supervised census data that came out every ten years, the correlations went away. It was a pretty clear signal that local officials were biased in reporting local data.

The Tianjin case specified in the question link occurred at the local municipality level. This is just another piece of anecdotal evidence that suggests what most China analysts already to know to be true — that if you add up provincial and municipality-level data, it exceeds national growth figures. Excerpted from an article from The Atlantic in 2013:

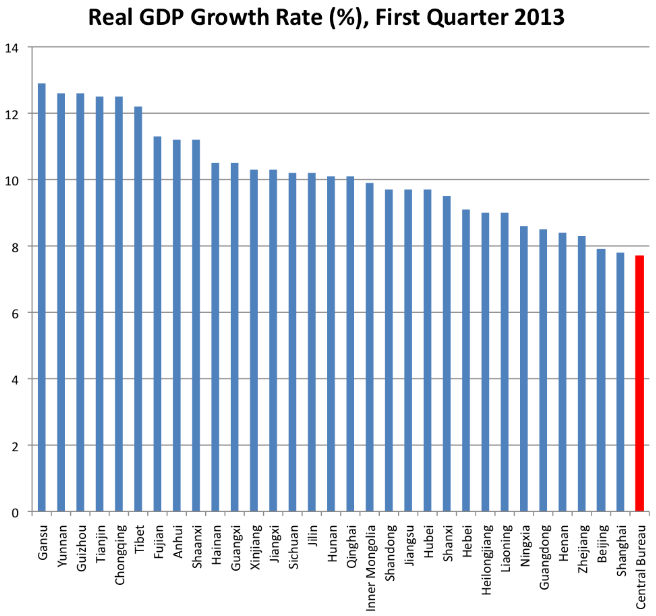

In the April, China's central government and provincial authorities released data on the country's economic performance for the first quarter of 2013. On April 15, the National Bureau of Statistics announced that the country's year-on-year real GDP growth rate had been 7.7 percent.

But something baffling arises when one compares the number published by the central government with those published by provincial authorities. By April 29, all of the 31 provincial governments had released economic statistics. Among them, in all defiance of the law of averages, no single province claimed a real GDP growth rate lower than the nationwide number. What gives?

The article from The Atlantic goes on to highlight some very important historical background:

In 1985, the national statistics bureau and provincial statistic agencies were separated into two non-interfering systems. Since then, economic data from each province have been gathered and calculated by each provincial agency independently. The national bureau has been charged only with accounting for national economic data, without relying on data briefed by each province …

… [these discrepancies are] partially explained by technicalities. When collecting primary data, the central bureau and provincial agencies sometimes use different basic “reference point” data and statistical calibrations. Second, certain inter-provincial economic activities are claimed by all the provinces involved, leading to double counting.

China’s National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) is organized into two separate bodies: One at the national level and one at the provincial level. These bodies do not coordinate and instead collect and analyze data independently.

If you think about it, based on this situation one should be even more suspicious if they actually ended up at the same number!!

National-level data is more accurate and less biased than local and provincial-level data. It is not perfect of course — no data collection system is — and has been exacerbated by the fact that historically China was a developing country with a large informal sector.

But things are starting to change. An October 2017 article from the South China Morning Post discusses how plans are in place to integrate the NBS by 2019:

China’s National Bureau of Statistics will take over data collection at the regional level from 2019, a government official said, replacing the current system in which the combined economic output of the nation’s provinces has long exceeded the official total for the country as a whole …

… the NBS would work with regional statistics agencies to compile regional data, with national and regional data to be released together once the new system is in place. The statistics office said it would push forward inclusion of research and development spending into regional GDP data, and would research methods for calculating service output from owner-occupied housing as part of improving its statistical methods.

No doubt this is in line with explicit policy direction from the Xi Jinping administration to emphasize quality over quantity as it relates to economic growth. From another October 2017 article by Bloomberg:

Chinese President Xi Jinping has quietly dropped a commitment made by his predecessor to double the size of his nation’s economy …

… That’s in line with earlier messages of tolerance of slower growth in exchange for stable development. Xi told a meeting of the Communist Party’s financial and economic leading group last year that China doesn’t need to meet the objective if doing so creates too much risk, Bloomberg News reported in December.

This is a very good development for China’s long-term economic prospects. Policymakers in China rely on data to make decisions. And to the extent data is flawed, logic dictates that you are going to end up making less optimal decisions.

The other thing that is speeding things up along the data accuracy front for China is that the data collection process itself is improving rapidly. One large driver is the fact that China’s formal sector is much larger than it was before. There is high correlation between having a large formal sector and how advanced your economy is — and China is getting very close to being classified as a “high income” economy.

The other driver is the proliferation of Alipay and Wechat Payments and digital payments replacing cash. This is generating an enormous amount of data (of the highest accuracy) across every sector and Chinese policymakers are leveraging it to improve everything from tax collection to real-time economic forecasting.

This was originally published on Quora in January 2018.