How successful is China's HSR system?

Comp to Interstate Highway build-out

When China’s high-speed rail (HSR) network was starting to come online in a big way (around 2011), I remember there being a fair bit of skepticism (particularly from outside of China) about the whole idea. “Too expensive”, “unnecessary”, “over-capacity”, “over-indebted”, “riddled with corruption” were commonly overheard refrains. In other words, it was just another “white elephant project” that would lead to some sort of crisis and if anything represented the epitome of China’s “broken growth model”.

Then the tragic Wenzhou train accident happened in July of 2011, where two high-speed trains collided and left 40 people dead and many more injured. That was probably the low point in public opinion towards HSR.

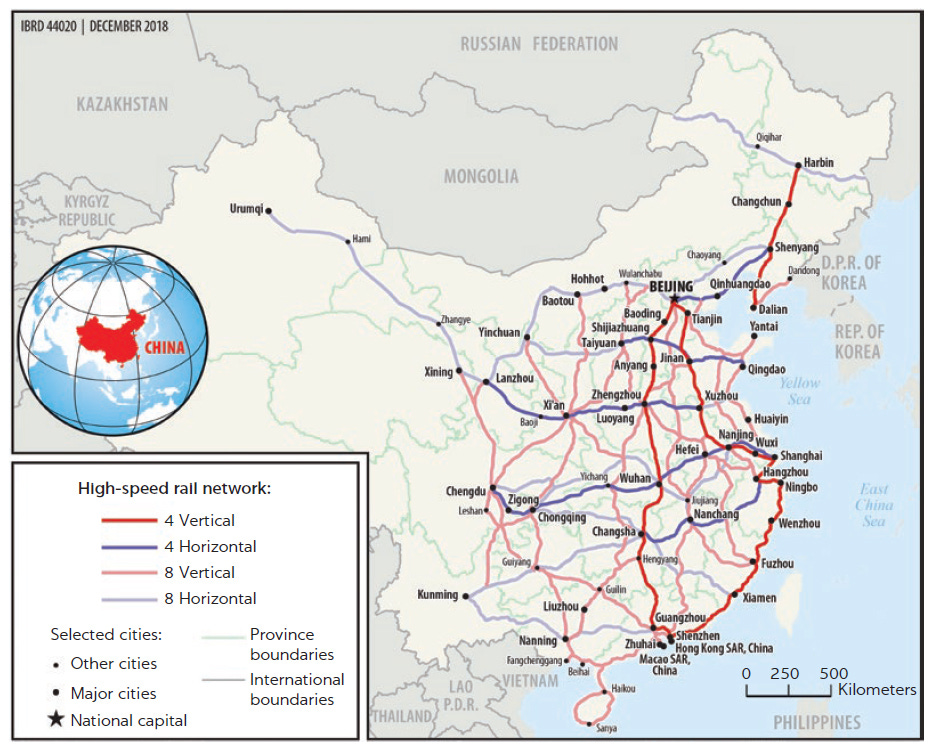

Since then, HSR has rebounded and surprised on the upside. Capacity utilization has been higher-than-expected, profitability has surprised most analysts and the network has continued to expand — today the network is three times larger than it was five years ago the government just announced plans to almost double the size of the network again by 2025. Trains are packed with not just wealthy Chinese urbanites but folks from across the socioeconomic spectrum. You can feel a great sense of pride when Chinese people talk about their shiny trains.

So can we now say that it has been a success? I am inclined to say “yes” but at the same time I think it might be too early to judge. Let’s take a look at another project to explain what I mean by this.

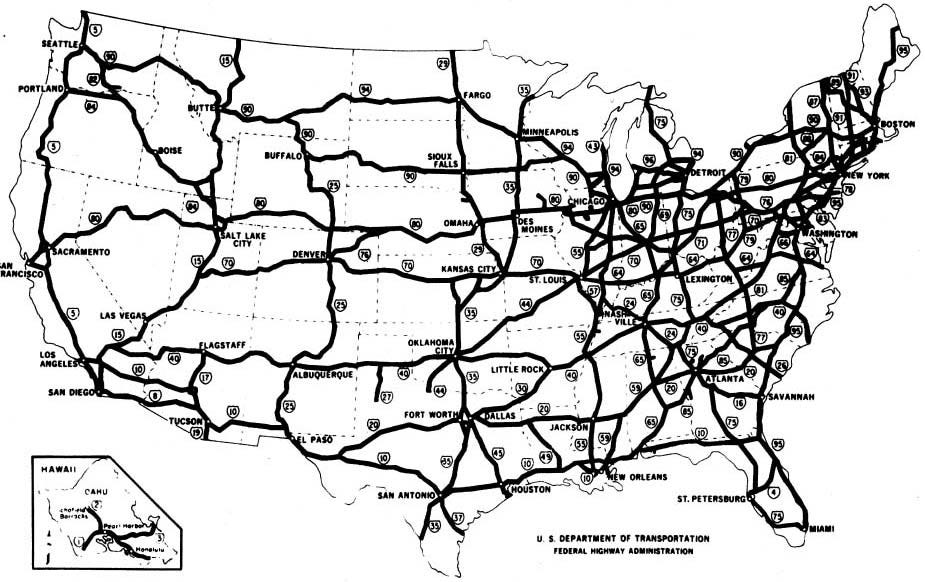

On June 29, 1956, President Eisenhower signed the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 which kicked off the build-out of the Interstate Highway system in what was to become one of the largest public infrastructure projects in history. $25 billion (~$225 billion in 2016 dollars) was approved for the construction of 41,000 miles of highway over a 10-year period — with actual construction of 47,000 miles over 35 years at a cost of around $500 billion in 2016 dollars.

Fast forward to the present day. The construction of the Interstate Highway System changed the landscape of America, enabling the construction of commuter suburbs designed around single-family homes and the automobile. As more American families moved out to the suburbs, our dependence on the automobile drove our thirst for oil and gasoline and the need to — starting in the 1970s — import vast amounts of crude oil from places like the Middle East. And our focus on the Middle East has clearly had major foreign policy implications leading up to the present day.

We can of course have a long debate as to whether or not these long-term ramifications have been positive or negative. But the point I want to make is that these were all unintended and unforeseen consequences — second and third-order effects. You see, the original rationale for this project was related to defense during the Cold War — to enable military resources to be transported across the country at a moment’s notice in case Russian paratroopers landed in Colorado. President Eisenhower championed this project after his experiences as a young military officer on a cross-country road trip after World War I.

With large long-term infrastructure projects such as the Interstate Highway System and China’s High-Speed Rail Projects, it takes a very long time to form an accurate view on the long-term effects. The unintended consequences and second/third-order effects are often felt decades (if not centuries) later and dwarf the original goals of the project in size and scope.

China’s HSR system build-out is similar in size and scope to Interstate Highway System project. As of early 2017, about 15,000 miles of high-speed rail track have been constructed for a total cost of around $33 million per mile (~$500 billion). Another ~12,000 miles of track are planned to be built out through 2025 alone.

China’s HSR has already had significant effects on traveller behavior, as we can see right now during the annual Chunyun (Spring Festival) which is taking place as I type. Similar to the rise of the suburbs in the U.S., you are starting to see urban development decision-making revolve around plans to open new HSR stations.

A lot can change in the coming years. For example, I am curious to see how autonomous driving software, plug-in electric automobiles and inexpensive electricity (via solar) will affect that economics and relative attractiveness of HSR — not to mention the costs of suburban living in the United States — compared to other methods of transport.

This was originally published on Quora in January 2017.