Why does Amazon to pay so little in taxes?

It's complicated

Amazon recorded a provision for income taxes in 2018 of $1.2 billion. Of this amount, $436 million was provisioned for U.S. Federal Taxes, $327 million for U.S. State Taxes and $434 million for International Taxes.

Out of the U.S. Federal Tax amount, $565 million was deferred and negative $129 million (i.e. “less than zero”) was provisioned for current-year obligations:

In accounting-speak, “provision” is a fancy way of saying “estimate”. For example, in 2018, the tax provision includes a “one-time provisional tax benefit of the U.S. Tax Act recognized in 2017”. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 reduced the corporate tax rate from 35% to 21%, and this shows up as a benefit for profit-generating corporations like Amazon. Translation: what happened here is that the previously estimated figure was re-estimated based on recent changes in tax laws.

Actual taxes paid are another matter, although it just so happens that for 2018 they were pretty much the same (also $1.2 billion). Normally, these numbers are different. Amazon’s 10-K does not provide a breakdown of this amount between U.S. Federal, U.S. State and International.

With this out of the way, let’s look at how Amazon managed to reduce its current-year U.S. Federal taxable income to the point where it could record a negative provision in 2018. Our tax code is complicated, and this means there are a lot of tricks that you can do to legally reduce taxes or push them out as far into the future as possible.

Aggressive re-investment

Amazon plays in a number of sectors that (i) feature significant long-term growth opportunities and (ii) require significant capital or technology investment to capture. Historically, the company has re-invested nearly all of its growth back into the business, including the creation of entirely new market segments from scratch — e.g. how it parlayed internal technology services into a third-party business (Amazon Web Services) that is now the largest contributor to consolidated group operating profit. Heavy re-investment, whether through capital assets (more on this below) or hiring of high-salaried technology workers, will serve to reduce taxable income.

It took a long time before Amazon started generating GAAP profits. Even after it started generating GAAP profits, the company still had to burn through all of the tax losses accumulated in the earlier, ramp-up years. It wasn’t until 2009 that Amazon’s retained earnings account on the balance sheet turned positive. And it has only been the last couple years where the company has really started to see its profits increase to substantial levels relative to its market cap.

On top of this, remember that U.S. companies keep two sets of books, one for GAAP accounting and the other for taxes. This is perfectly legal, as the rules for tax treatment are often very different than GAAP treatment. This means that even as its accumulated GAAP earnings finally caught up in 2009, accumulated losses for tax purposes would take much longer to burn up.

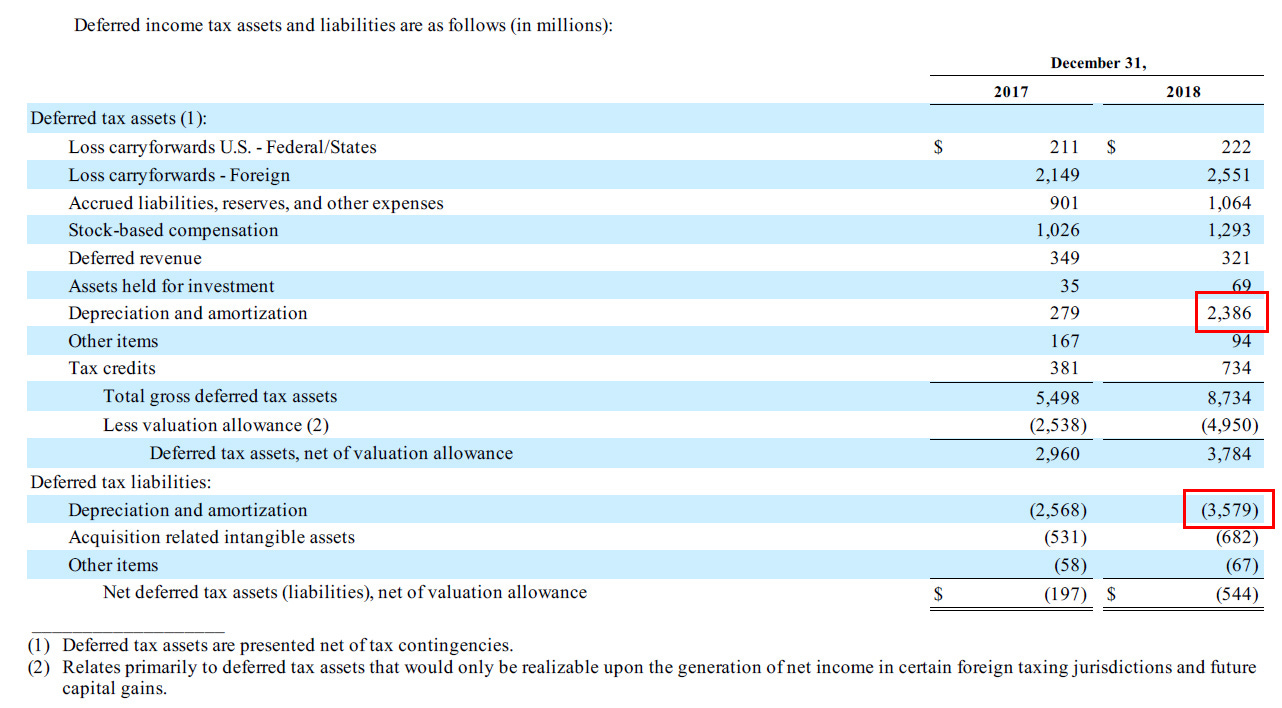

One of the key GAAP vs. tax accounting differences that Amazon takes advantage of is accelerated depreciation.

Accelerated depreciation

Amazon is a capital-intensive business that requires significant capital to grow, both for its core e-commerce operation (logistics and fulfillment) as well as its technology services (Amazon Web Services). For e-commerce, it invests in warehouses and the equipment and machinery within the warehouses. For cloud/technology services, it invests in servers, networking equipment and some capitalized software development to expand capacity to meet both internal needs and that of third-party customers.

These investments are typically made via something called a “capital lease”. Capital leases allow companies to finance the purchase of long-lived assets, but for tax purposes treat them like normal capital assets. As a capital asset, the company can take a depreciation charge for tax accounting purposes. Companies typically try to “accelerate” as much of the depreciation as possible, which has the net effect reducing current-year taxable income by pushing profits farther out into the future.

This accelerated depreciation shows up in something called “deferred taxes”. When a company pushes taxable income into the future, this shows up as a future liability on the balance sheet through the deferred tax liability account. To the extent tax laws stay the same, at some point the company will need to pay those taxes. Of course, most companies, Amazon included, try their best to push the actual bill as far out into the future as possible.

Other cool tricks

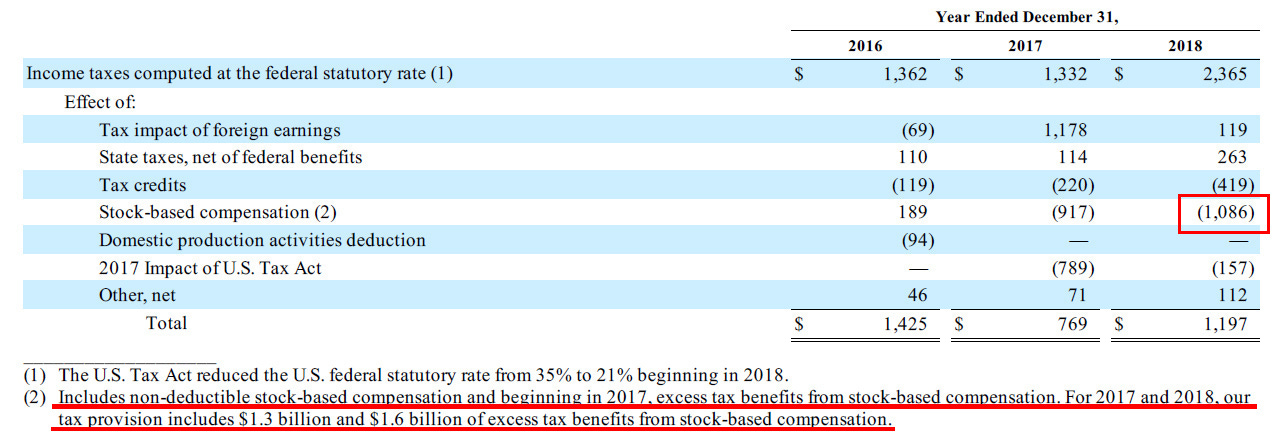

Interestingly, the largest adjustment to Amazon’s 2018 income tax provision was an adjustment made for stock-based compensation.

Stock-based compensation arises when companies like Amazon issue stock options to employees. When equity is awarded to employees, a complicated calculation is performed — typically by the HR department — to calculate the value of the equity, using models with fancy-sounding names (e.g. the “Black-Scholes” formula).

However, in the time from when the equity award was issued to when it was exercised, the share price invariably changes. In the case of Amazon, the direction has historically been upwards, often at a very steep slope!

When this happens, tax accounting rules[4] allow the company to calculate how much higher the realized equity award was compared to the original estimate. The difference between these two numbers gives rise to something called “excess tax benefits from stock-based compensation” and has the effective of lowering current-year income tax provisions.

This is one reason why companies love to issue options!

Profit-shifting

Another common practice is maximizing the allocation profits to overseas entities in jurisdictions where tax rates are lower. The most profitable segment within Amazon is its cloud/technology services division, and a not-insignificant proportion of these revenues are generated overseas. As I discuss here, because of the intangible nature of technology and software services, it is quite easy to structure things so that a big chunk of these profits are recognized offshore to lower the overall tax bill.

In my view, Amazon is actually not as aggressive compared to some other technology companies at shifting profits overseas. A big part of this is, as described earlier, Amazon does not generate significant profits to begin with (again, relative to its market cap). The other reason is that a significant amount of its profit is actually generated onshore vs. offshore. For example, its International operations are barely profitable (as you can see in the first table above).

However, as the company’s profits start to significantly ramp up, expect more of an effort to use international tax havens like Ireland and the British Virgin Islands to minimize its overall tax bill.

As it states in its 10-K (p. 63):

“… we intend to invest substantially all of our foreign subsidiary earnings, as well as our capital in our foreign subsidiaries, indefinitely outside of the U.S. in those jurisdictions in which we would incur significant, additional costs upon repatriation of such amounts.”

I just want to add that even though Amazon’s corporate tax bill is relatively low (or even non-existent) at the federal level, the company is still responsible for generating significant tax revenue when you analyze things holistically. Amazon pays tens of billions of dollars in wage and compensation income to its employees, the majority of whom are based in the United States. A significant portion of the wages will fill government coffers in the form of federal and state-level income taxes.

Its spending (on capital leases and other non-compensation related expenses) also indirectly generates taxable income for other companies in its eco-system.

Finally, unlike many other multinational corporations, Amazon is actually heavily investing back into the United States, both in terms of hiring workers and investing in next-generation warehouse and datacenter operations.

This was originally published on Quora in February 2019.