How can China become less dependent on real estate for growth?

China must shift to consumption

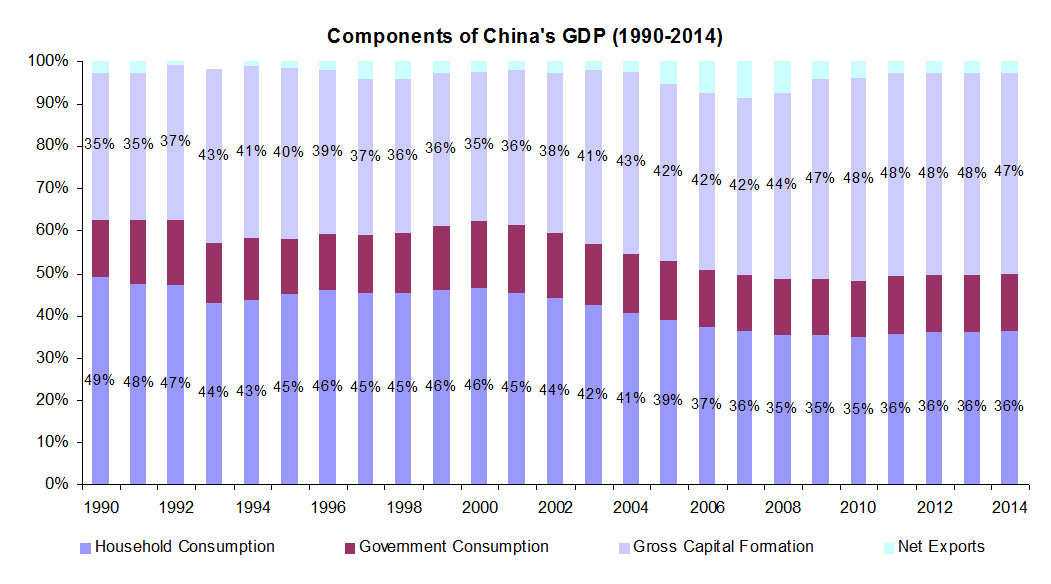

Remember that GDP has 4 components:

Gross capital formation (“Investment”) (47% of GDP) – this is where real estate construction goes.

Household consumption (“Consumption”) (36% of GDP)

Government expenditures (14%)

Net exports (3%)

In economics parlance, becoming “less dependent on real estate value to fuel growth” translates to needing to rely more on household consumption and net exports to make up for the decline in Investment. In other words, reversing the trend that we have seen since the early 2000s:

Easier said than done.

Whereas you can artificially inflate Investment through things like financially repressive policies, household consumption is based more on how well the underlying economy is doing [1]. And net exports are a function of trade, which is subject to the desire of other countries to trade with you – it can be crimped by growing protectionism, as an example.

As I discuss in another answer, dismantling some of these financially repressive policies could ultimately have an accelerating effect on consumption in the long run. If consumption had been repressed by these policies before, it stands to reason that, once liberated, like a recoiling spring it would accelerate.

But as Investment is such a large proportion of GDP, it will take a lot of growth in household consumption to make up for any deceleration or decline in Investment. At the same time, disrupting the status quo too quickly could lead to disruptions in household spending as well. So the Xi administration has a delicate balancing act to deal with.

The different scenarios depend on two key variables:

How fast is the transition period as the policies change and shift the focus from Investment to Consumption?

The amount of “malinvestment” i.e. the percentage of historical accumulated investment is actually bad?

The economy will need time to “absorb” the accumulation of bad investments so the range of potential scenarios is based on the answers to these two questions (I don’t have the answers, but am curious to find out).

I define the “hard landing” scenario [2] as having to absorb massive (e.g. 30-40% rate of malinvestment) losses over a short period of time (i.e. shock therapy style reform).

A “soft landing” to me would be absorbing something more like 10-15% losses over a longer period of time of gradual reform.

And there are of course an infinite range of scenarios in the middle (and at the extremes as well; my figures are only gut-based).

That said, my gut tells me that the 30-40% rate of malinvestment figure is high. It may have gotten that bad at the peak of the credit cycle (especially in the non Tier I and II cities) but in earlier years the rate was very likely much lower.

My gut also tells me that the Xi administration will implement reform at a rate they feel comfortable won’t cause such severe disruptions that extreme scenarios [3] start to rear their ugly heads. And I think there is still enough reserve firepower to maintain such stability.

Again, these are only gut feelings at this point but I hope this gives you some framework for evaluating the changes that are coming.

Notes

[1] Growth in household consumption has tended to track the global economic cycle much more closely than gross capital formation (GCF). For example, from 1991 to 1996, nominal growth averaged 24%, but between the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 and the post-9/11 global recession, growth dipped to 8% for the next six years. Then, as the rest of the world picked up, growth shot up to 14% through 2008 before slipping in 2009.

[2] Most folks out there define “hard landing” as based on the GDP growth rate falling below a certain level, but I think this doesn’t reflect the key issues at hand. Falling below 6% GDP could be good for China in the long run if GDP consists of much higher quality (e.g. more sustainable over the long run).

[3] Regime “change” for one.

This was originally published on Quora in September 2014.