Will "shadow banking" in China lead to a financial crisis?

Credit intermediation in China

The 2008 Global Financial Crisis was so painful and acute in large part due to how complex the modern, global financial system had gotten. One measure of complexity is the number of intermediaries that money passes through on its journey from the original lender to the ultimate borrower.

For example, with the now infamous sub-prime CDOs (collateralized debt obligations) that really kick-started the 2008 Financial Crisis, it was very common to have more than a half-dozen intermediaries sitting between the original lender and ultimate borrower:

Sub-prime homeowner borrows money to buy a property.

Originating bank sells the loan to a third-party e.g. investment bank.

Investment bank combines loan with other loans from other originating banks into a mortgage-backed security (MBS).

The MBS is “vertically sliced” into different tranches (i.e. AAA, AA, A, BBB, etc.), as rated by the ratings agencies.

Each tranche is sold to a different type of investor that specializes in that level of risk.

Some tranches are sold to other banks or investors that are looking to re-package them into CDOs.

The CDOs are also spliced into different types of securities and sold onto other investors.

Some of these investors are also combining CDOs with other CDOs to create CDO-squareds.

CDO-squareds could be re-packaged again and again but let’s say that it finally ends up in the account of a fund that intends to hold them for the long-term (such as a pension fund or an endowment).

But even these funds typically have their own own investors and constituents, adding yet another intermediary to the funds flow.

The technical term for this process is “credit intermediation”. And as you can see, it could get pretty complicated. Too much complexity exacerbates many issues related to credit intermediation such as the Principal-Agent problem. Complexity also increases the vulnerability of an economy to shocks. These issues, compounded, ultimately contributed to the 2008 Financial Crisis.

For a more entertaining (and perhaps better) explanation, I recommend watching this segment from “The Big Short” featuring Dr. Richard Thaler and Selena Gomez:

Although the term “shadow banking” sounds murky and nefarious, in China the level of complexity with these products is still nothing compared to what I described above.

For example, with the wealth management product (“WMP” or 理财产品), you typically have two intermediaries between the lender and ultimate borrower — a channeler (typically a bank) and a “Trust Company”. Here is a typical money flow:

A retail customer buys a wealth management product from his/her bank.

The bank channels these funds to a Trust company. The bank could decide to guarantee the principal (or not).

The Trust Company lends the funds to the end borrower, e.g. a private enterprise looking to fund a growth initiative.

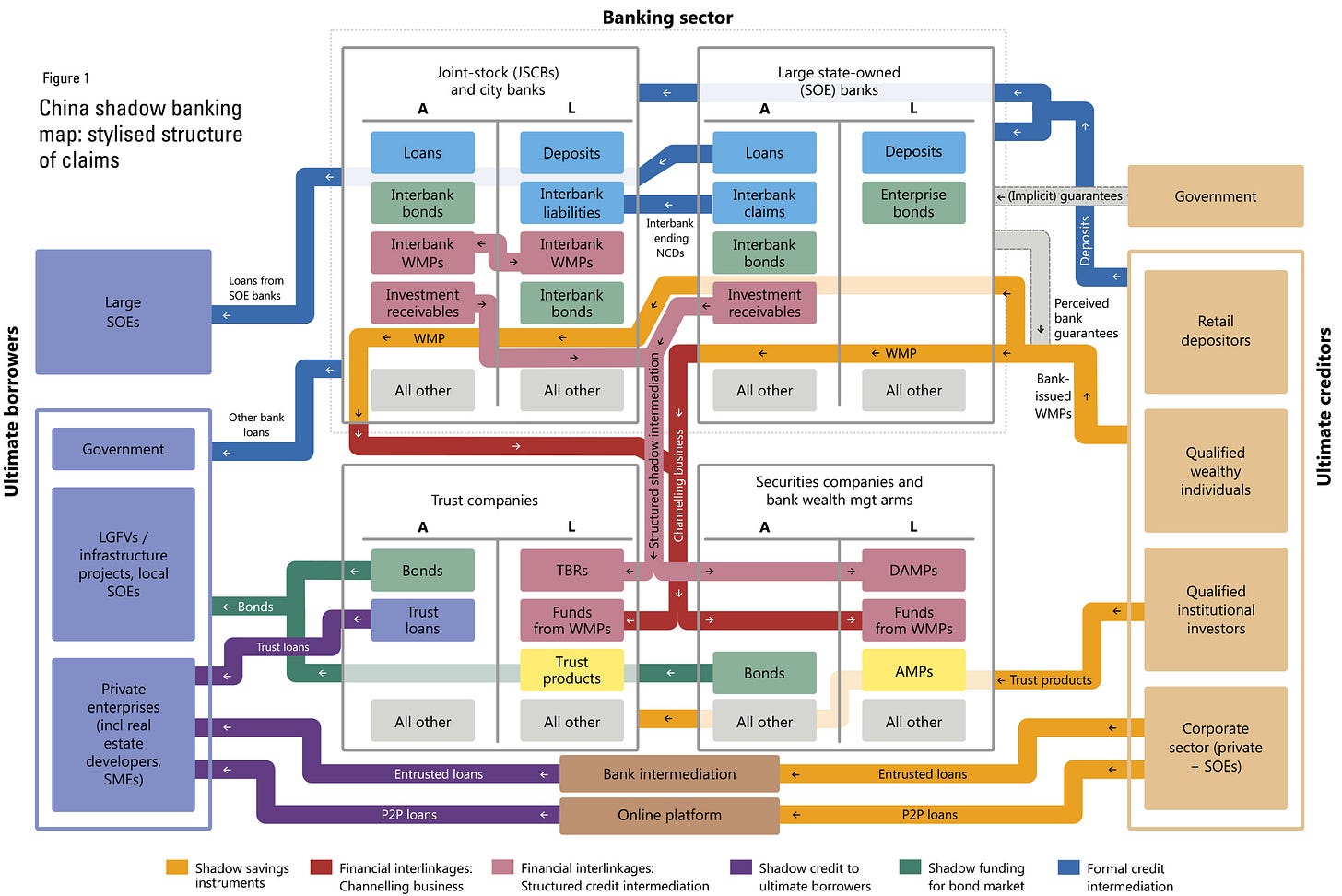

You can see the steps and intermediaries graphically in the flow chart below, following the path from left to right:

China’s financial system has certainly increased in complexity over the last decade as a result of significant reforms and changes. However, you have to remember that it started from the lowest possible base: a decade ago, the vast majority of funding was comprised of direct lending from the bank to the borrower. In other words, we were talking about just a single credit intermediary.

The introduction of “shadow banking” products took that number to two or maybe three in extreme cases.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the typical shadow credit intermediation process involved seven intermediaries and could often have even more as illustrated in the sub-prime CDO-squared case above. From the excellent report from the Bank of International Settlements discussing China’s “shadow banking” system:

Shadow banking in China is less complex than in the United States, as it involves fewer entity types and fewer steps of credit intermediation. Mostly, shadow credit intermediation in China is a one-step or two-step intermediation process, as it is effectively based on “plain vanilla” loans or instruments that entail a one-to-one link to the revenues from the underlying debt instruments.

In contrast, a typical shadow credit intermediation process in the United States involves seven steps (“vertical slicing”) and a large number of financial entities.

Nevertheless, the tight linkages between shadow savings instruments and bond market, as well as the new forms of structured shadow credit intermediation, signal that shadow banking in China is growing more complex.

Even with significant reforms, China’s “shadow banking” system is still far less complex than modern financial systems that we see in fully developed economies. As such, the situation in China today is nothing like the situation in the days leading up to the Global Financial Crisis.

The last point I want to make is that “shadow banking” reforms in China are actually helping to funnel financing to the more productive parts of China’s economy.

Historically, when the only credit available was from loans via state-owned banks, private enterprises struggled mightily to access any sort of credit. Nearly all bank loans went to state-owned enterprises, many of which were inefficient and/or did not serve a purely commercial function.

As such, funding-starved private enterprises typically had to rely on equity sourced from individuals (friends, family and business affiliates) or foreign investors (FDI). Once they became profitable, retained earnings — another form of equity — became the primary source of growth financing.

But equity funding is the most expensive type of funding. And the privileged few private sector companies that could actually access any sort of credit (typically via private loans) paid much higher rates than what SOEs could access from the banks.

That is why China’s private sector companies (especially those outside of the real estate sector) tend to be extremely capital-light. The ones that made it through the crucible of brutal competition that is China are self-selected to be extremely efficient because they had to be just to survive.

Today, the best-run, most competitive and most efficient companies in China come out of its private sector. Despite the significant funding disadvantages described above, the private sector was still able to drive the majority of China’s economic growth over the past four decades.

Unlike bank loans, “shadow banking” products in China are more accessible to these private sector companies. So now, instead of borrowing at double-digit interest rates or issuing expensive equity to fund growth initiatives, they have better access to credit financing at a more reasonable rate, e.g. 6% to 8%. In other words, via “shadow banking”, the most productive companies in China have greater access to credit financing.

More than ever before, credit is finding its way to the most productive and efficient parts of the Chinese economy. This is a good thing.

This is just another reason why the narrative that “shadow banking” reforms will lead to a major financial crisis in China could not be further from reality.

This was originally published on Quora in October 2018.