Could China become another Japan?

China is Japan in the 70s, not the late 80s

There are some major differences between China today and Japan in the late 1980s on the eve of its entering its long “stagnation”. One is relative stage of development, which impacts the amount of “catch-up” growth left to go. On this measure, China is more similar to the Japan of the early 1970s than the late 1980s.

The other is scale, and this has implications on the possible paths that China can take to become a fully developed country. China’s economy is certainly not immune to stagnation, but if does happen, it will be for different reasons which I discuss below.

There are similarities as well. In particular, both China today and Japan in the 1980s built up heavy debt loads and both had to deal with declining (or as some economists argue, negative) returns on marginal investment. Japan dealt with this by transferring debt from the corporate sector to the government, without necessarily addressing the underlying inefficiencies and that was a big part of why they haven't been able to claw their way out of stagnation. China is starting to take the right steps by removing the “financial repression” tax on the household and slowing down debt growth [1]. But it is still really early in the re-balancing process.

Let me also just add that becoming “another Japan” is nothing to scoff at. Even though GDP growth has slowed, the quality of its GDP has improved and nobody will argue with you if you say Japan’s got the best quality of life by far in Asia, with HDI metrics that are on par with the most developed Scandinavian and Northern European countries.

Stage of development

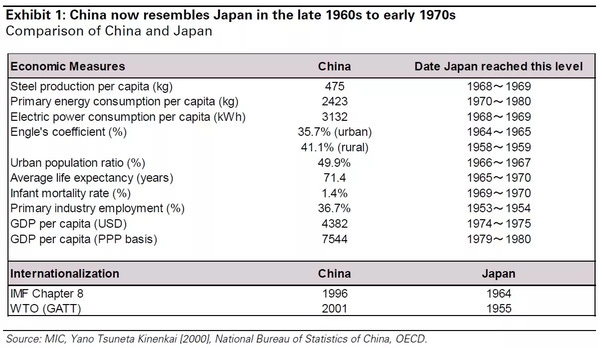

China is still in the middle stages of development. Around 10-15% of the population still lives below the poverty line, mainly in the countryside. Japan had already caught up with the world’s most productive economies by the early 1980s. Looking at factors like steel production, energy consumption, urban population ratios as well as HDI comparisons, China today is at the levels Japan reached in the early/mid-1970s. This chart below is from a Goldman Sachs report from 2012:

The automobile industry is another good bellwether of industrialization and economic development. Interestingly, China just recently started exporting automobiles to the United States. By comparison, Japan started really ramping up its automobile exports five decades ago, in the 1960s. As an aside, South Korea entered the U.S. market in 1986 with the Hyundai Excel -- another decent proxy implying that China is around where South Korea was in the mid-1980s.

One of the major implications here is that China probably still has another decade or so of "catch-up” type growth left, especially on the consumption side of the GDP ledger. Japan saw robust growth rates through the late 1980s and South Korea saw the same until hitting a wall in 1998 during the Asian Financial Crisis.

Scale and its implications on an export-led development model

One obvious difference between China and Japan (and even moreso with South Korea) is the level of scale. Japan is a large country and was the 7th-most populous country in 1990. But China’s population is over ten times that of Japan’s.

This difference in scale means that China cannot follow Japan’s path and realistically hope to become a rich country. Like China for most of the last three decades, Japan’s strategy was to emphasize the development of its export sector, and their success in this led to large trade surpluses with the world. In 1986, Japan’s trade surplus peaked at $83 billion. In today’s dollars ($180 billion), this worked out to $1,500 per Japanese person. Those levels prompted severe backlash from its trading partners, especially the United States; this was the era of books/movies like Rising Sun and xenophobic-driven tragedies like the murder of autoworker Vincent Chin (a ethnic Chinese guy who was mistaken to be Japanese) by disgruntled autoworkers/thugs.

China’s trade surplus peaked at $350 billion in 2008 ($280/person in today’s dollars). Similar to Japan in the 1980s, by then China was already starting to see severe backlash against it in the years leading up to the 2008-09 Global Financial Crisis (GFC). The scale of China’s trade imbalance was having rising and disproportionate effects on things from global interest rates to commodity prices to unemployment rates. It certainly was not the only reason behind the GFC but it was likely one culprit. In any case, the GFC and the ensuing economic depression went a long way to prick this imbalance and we have likely seen the its peak. The result was that China realized it could no longer depend on growth in net exports to drive its GDP, and unlike Japan, it hadn’t yet become a wealthy country when this happened.

Scale and its implications on a consumption-led economy

While China could not “export its way to wealth” like Japan and a few other East Asian countries did, there are some nice advantages to having scale.

Having such a large population means that you will inevitably have the largest home markets for most industries. Unlike Japan, China can utilize this massive domestic market to become the main driver for the economy and innovation going forward. Japan had a decent-sized market, but even then it was less than a third the size of America’s. It was good enough to get many industries off the ground but to become truly wealthy, Japan had to figure out how to sell to the rest of the world (which they did very well).

One interesting case study that illustrates this concept is mobile telephony. In the 1990s and early 2000s, Japan was the world leader in mobile telephony. I still fondly remember my state-of-the-art Sony Ericsson t-series mobile phone that were one of the first “feature phones” that could play MP3 ringtones, snap high resolution pictures etc. When I brought it back to the U.S. in 2004, I remember my friends being quite impressed by my distinctively non-MIDI ringtone [2]. Back then, almost everybody in Japan bought their cellphones from Japanese mobile phone companies and Japan developed its own proprietary network technology for its home market.

Today, things are very different. Basically, it came down to the fact that Japan’s home market did not have enough scale to support its domestic industry. Their network got bogged down with older proprietary technology as other countries moved more quickly to adopt standardized 4G technologies like LTE. They were late to the smartphone game. In today’s standards-driven smartphone world, you probably need a minimum of half a billion customers to support enough industry scale to survive. South Korea was more successful transitioning into this new world because it knew from the beginning that it could not rely solely on its home market to succeed.

In contrast, China’s home market has proven to be large enough to create a sustainable market for its domestic brands, and not just for hardware but the entire Internet ecosystem [3] as well. Chinese users primarily [4] use Chinese-made, Chinese-branded smartphones that are built on top of a Chinese flavor of Android, search on Baidu and use primarily Chinese-developed apps bought from Chinese app stores. And outside of not being able to access Facebook, this hasn’t held back the development of a thriving mobile/Internet ecosystem. In fact, today the smartphone and mobility probably play a much larger role in the lives of your average Chinese middle class consumer than even most developed countries.

From this perspective, China’s economy in the future -- if they are successful in executing this current economic transition -- will actually look a lot more like the United States than Japan or South Korea. Notably, the United States is wealthy not because it is a major goods and services exporter generating massive trade surpluses with the rest of the world (quite the opposite). In fact, the United States actually ranks near the bottom amongst large developed economies in Trade as a percentage of GDP [5]. It is wealthy because its consumer economy is the largest in the world by a wide margin, and it has the world’s finest entrepreneurs that can leverage this engine to find innovative ways to not only meet this demand but create new demand by coming up with products and services the world has never seen before.

This virtuous cycle of consumer demand driving innovation is a powerful flywheel that China is still trying to build in its attempt to emulate the United States. It is still early in this process. Whether it can figure this out over the next two decades will be the most important determinant of whether it can -- like Japan by the early 1980s -- become a wealthy country.

Notes

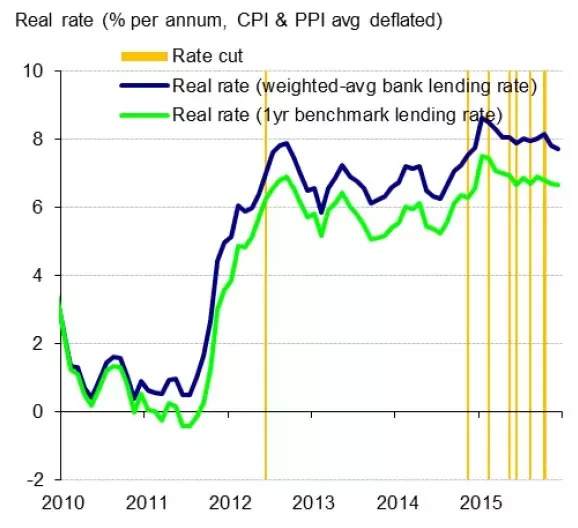

[1] Lending rates in real terms have increased from close to 0% in 2011 to approx. 8% today. Pretty massive move. No surprise that debt growth slowed markedly after 2011 from the 20%+ nominal growth rates in prior years. Chart below from UBS:

[2] Lil Jon’s opening hook from Usher’s “Yeah!”

[3] Frankly, I think the main reason that China has restricted Facebook and Google is less to do with controlling “freedom of speech” but giving home-grown companies like Baidu and Tencent enough of a head start to dominate the Internet industry.

[4] One notable exception is Apple and the iOS eco-system, and that is because Apple is awesome.

[5] This does not mean that Americans don’t trade. There is a hell of a lot of trade going on, but most of it happens internally (state-to-state, city-to-city etc.) which would not get counted in this statistic.

This was originally published in Quora in January 2016.