Should China continue to invest in high-speed rail?

The merits of expanding from a 4x4 to 8x8 grid

Bloomberg: China Doesn’t Need 125,000 Miles of Track

“For all the patriotism that comes with ambitions to build more high-speed rail, it’s a bad idea.”

David Fickling writes that China’s investment in its high-speed rail network is driven by “patriotism”. But if you dig into the numbers there are many reasons to suggest that it is driven by actual economic returns and that the build-out should continue to connect smaller Tier 4-5 cities in the populated regions of the country.

Debt service

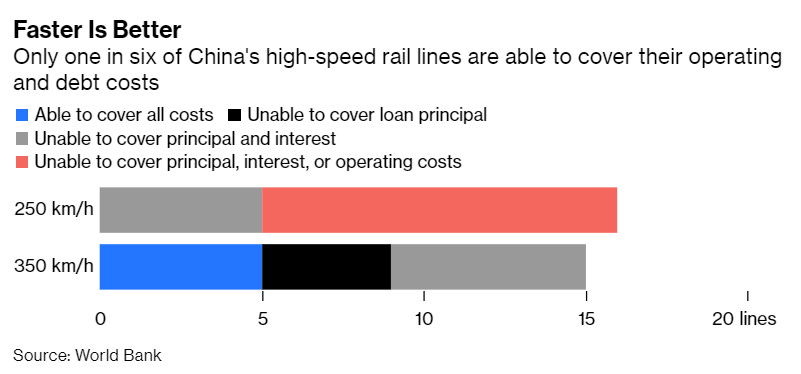

One key component of David’s argument is that many of China’s HSR lines are unable to cover their debt service costs, citing a World Bank study that is summarized in this key chart:

A World Bank study last year found that only five out of the 15 fastest 350kmh lines cover their operating and capital costs, while six are unable to pay the interest on their loans. The situation is worse for the 250kmh lines that make up the bulk of high-speed traffic: Just five of 16 lines were able to cover their operating and maintenance costs, and none had the profits to pay back interest, let alone debt principal.

But as I argue below, this debt service threshold it uses is very strict, especially for younger, immature networks (e.g. Chinese HSR). It is a requirement that few (if any) passenger networks would pass – not even Hong Kong’s highly regarded MTR system:

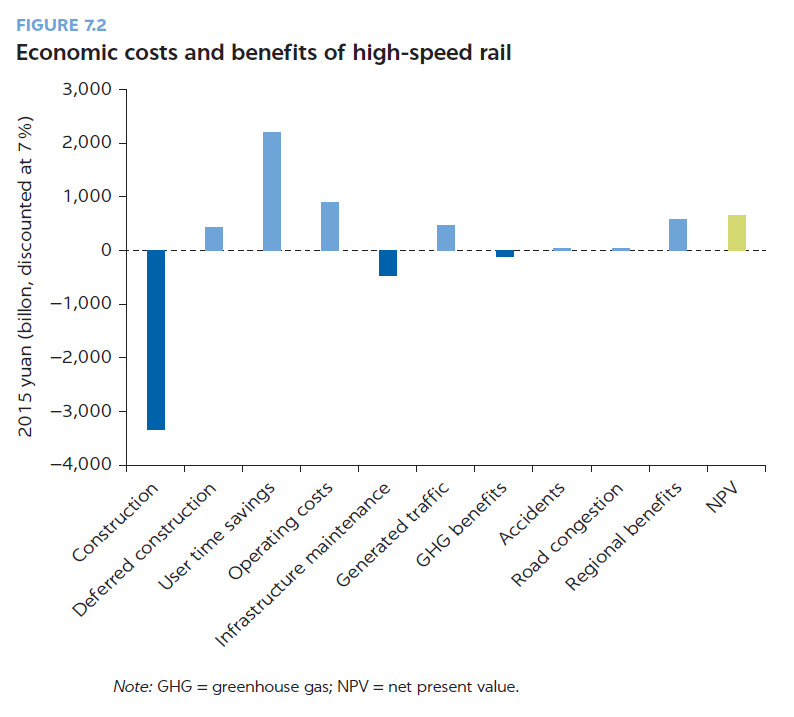

Further, this data has been somewhat cherry-picked: the same World Bank report concludes that as of 2017 Chinese HSR has generated “positive” economic returns when you examine comprehensive costs and benefits – not just financial metrics in a vacuum.

Economic benefits also accrue from reductions in operating cost as users of higher-cost modes such as automobile and air transfer to HSR. These transfers also generally reduce externalities (accidents, highway congestion, and greenhouse gases). Benefits also derive from the deferral of the need to invest in expanding the capacity of other modes as a result of demand transferring to HSR.

Other economic benefits are associated with improved regional connectivity. HSR can contribute to rebalancing growth geographically to reduce poverty and enhance inclusiveness.

Overall, the economic results appear positive, even at this early stage. The economic rate of return of the network as it was in 2015 is estimated at 8 percent, well above the opportunity cost of capital adopted in China and most other countries for such major long-term infrastructure investments. There is thus a reason to be optimistic about the long-term economic viability of the major trunk railways of the HSR program in China.

Why Phase II may be even better than Phase I

The Bloomberg article goes on to argue that while perhaps the 1st phase of Chinese HSR may have been fine, it would be a “bad idea” to proceed with a second phase that doubles its size, arguing that cost of incremental track is not justified by incremental benefits.

Those achievements look modest next to what’s planned for the coming decades. China State Railway Group put out the sequel to the 2004 plan last week, promising a network 200,000 kilometers (125,000 miles) long by 2035, up from 141,000 kilometers now. High-speed tracks will comprise 70,000 kilometers of the total — roughly double their current length.

For all the nation-building pride that can attach to such ambitions, it’s a bad idea.

China’s high-speed rail network is already bigger than it ought to be. The entire route from Beijing in the north to Guangzhou in the south is barely more than 2,000 kilometers. A 70,000-kilometer network would have to extend deep into the backwoods, to cities like Kashgar in Xinjiang and Shigatse in Tibet. Already, too much spending has gone on serving areas where the population is too small and low-income to make high-speed rail viable. Further extending train lines to yet smaller cities will make that problem worse.

But there are many reasons to suggest that the opposite is true. First, as described earlier, the World Bank already concluded that the existing HSR build-out has generated a positive economic return based on 2017 financials.

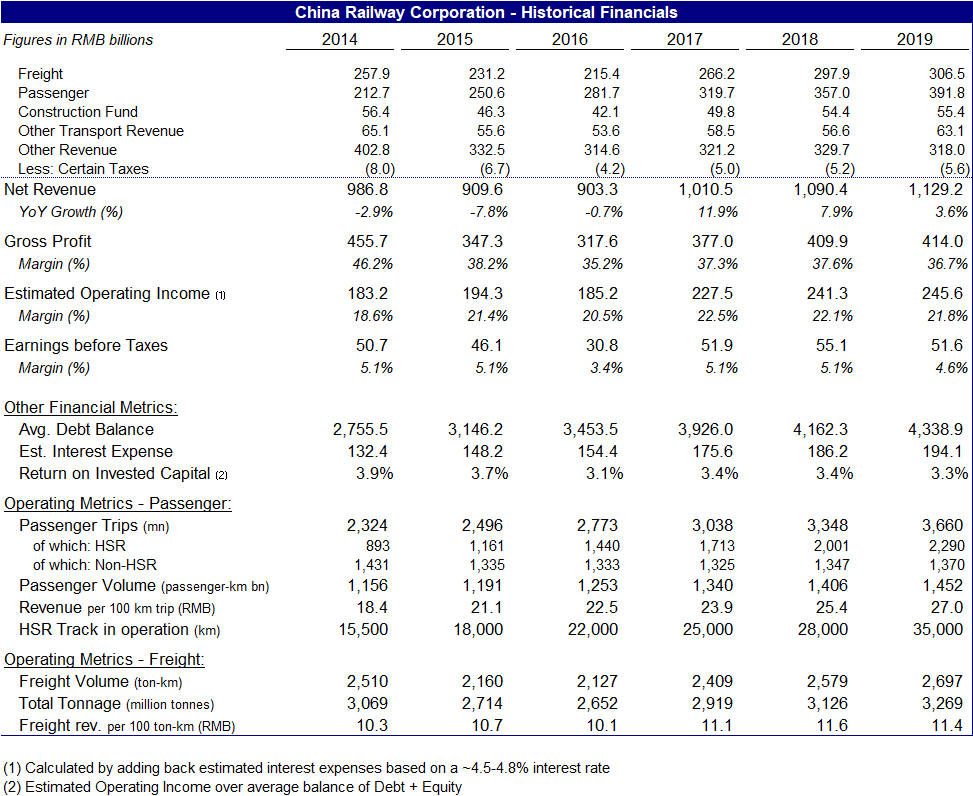

Fast forward two years, China Railways’s financials have only improved, largely driven by growth in the high-speed rail segment. As one of the largest domestic bond issuers in the country, the financials of China Railway, which operates the country’s passenger rail network and most of its freight, are publicly available:

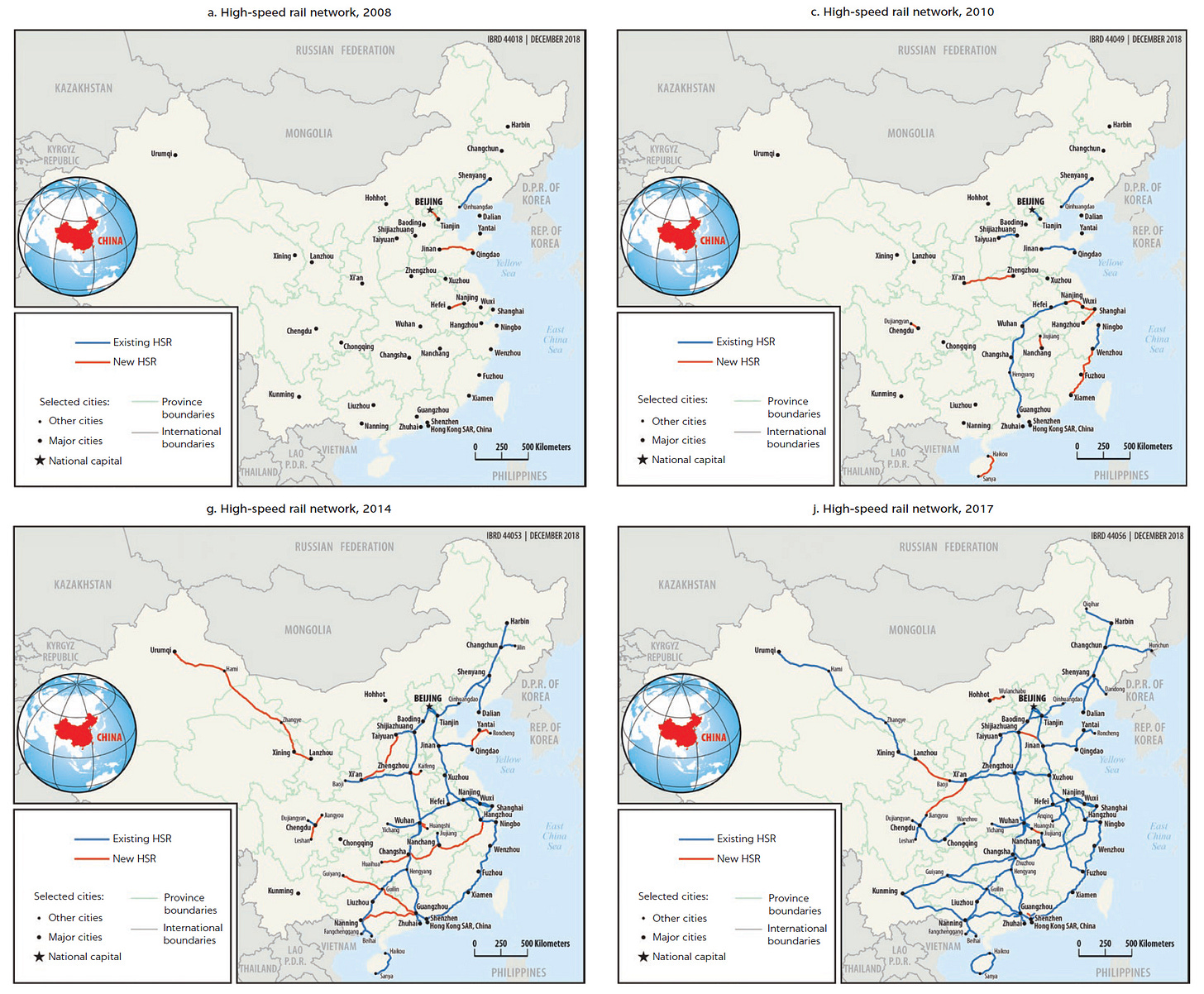

Case studies have shown that there are powerful network effects to growing passenger rail … networks. The report discusses how existing HSR lines have seen significant boost in volume when new, adjoining lines are added:

Many opportunities have developed to connect cities through services over a combination of lines, with, for example, direct trains between Beijing and Xi’an via Zhengzhou. Networking is an important feature of Chinese HSR. North–south vertical lines and east–west horizontal lines provide the basic network skeleton, supplemented with regional and intercity railway lines.

Each HSR line thus creates flows for other lines. For example, 24 percent of the passengers traveling on the Beijing–Shanghai line in 2016 were traveling to and from stations that were not on the line itself but on connecting lines. Another example is the Zhengzhou–Xi’an line, which until 2012 was an isolated line, serving only passengers between Zhengzhou and Xi’an. After it was connected to the Beijing–Guangzhou HSR in 2013, passenger volume increased by 43 percent and passenger-km by 72 percent.

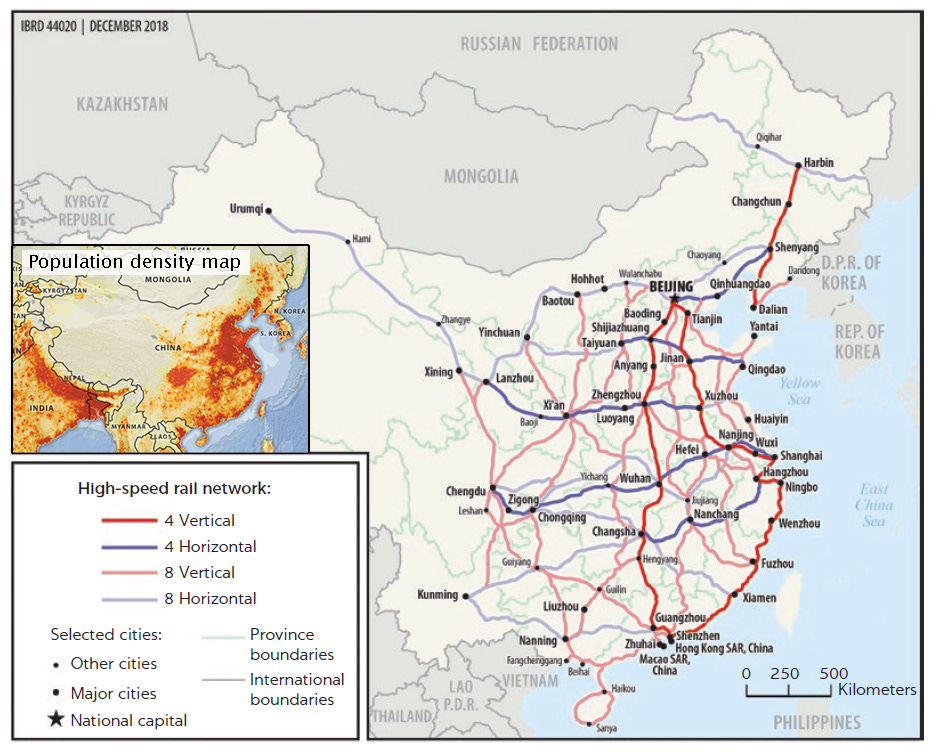

China’s urban topography is well-suited for high-speed inter-city transport as there are hundreds of cities with over 500,000 residents that are separated at distances – between 200 and 500 km – that are ideal for HSR vs. transportation alternatives. Further, these cities tend to be dispersed in a spider-web like configuration, which allows you to build “hub and spoke” type networks that can maximize utilization.

However, when China first started building out HSR, most lines were isolated point-to-point routes that did not connect with other routes. Today, most of the lines have been connected in a 4x4 grid pattern. Connecting the networks increases usage and increased utilization improves returns.

The second phase of the HSR plan is to turn this into an 8x8 grid pattern. This is less about connecting “backwoods” cities like Kashgar and more about connecting regional Tier 4-5 cities situated around the major Tier 1-3 cities that are already connected. The stated goal is to have every city with over 500,000 in population connected to a high-speed rail line.

Notice in the map below how nearly all of the lighter “8x8” lines are located in the highly populated areas in China.

As new lines are added, they should not only enable new point-to-point traffic, they will also feed new traffic into existing trunk lines. In other words, as the HSR network matures, if anything these network effects should enhance and not detract from returns.

Financial vs. Societal Returns

Another important point is that passenger rail networks should not just be evaluated on the basis of financial returns, but on total societal returns. As a public asset, the rail network is not trying to maximize profit or return of capital from a purely financial perspective.

Profitability can be maximized at China Railway by simply increasing fares, but doing so would eat away the societal value of enabling the masses to travel comfortably, affordably and at great benefit to the environment vs. alternatives. More important than financial returns is affordability, and by most measures HSR in China is quite affordable.

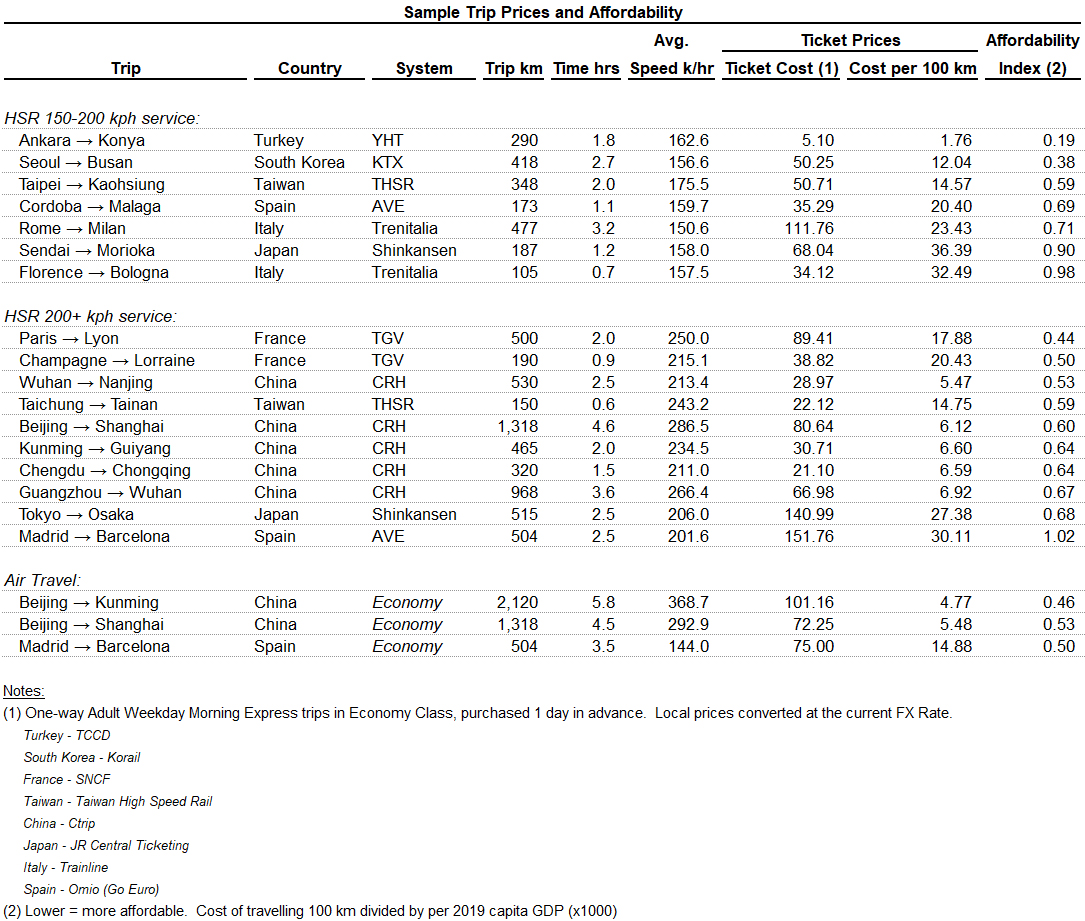

Fares are reasonable, and if you travel in the 2nd-class compartments, there is a healthy mix of local and migrant travelers. I recently put together some information that calculated the relative affordability of high-speed rail across several different countries with HSR systems and China was right in the middle.

As disposable incomes in China continue to rise, affordability should only increase over time.

In Chapter 7, the World Bank report attempts to measure the economic return (as differentiated from financial return) by accounting for all the various benefits and costs. This is how they arrived at the aforementioned 8% economic rate of return.

Finally, the assumption that the HSR build-out is driven by “patriotic” reasons is just speculative and highly subjective. One could simply ask why wouldn’t it be perceived as equally “patriotic” to reform the hukou system or build a modern, national healthcare system?

Perhaps there are other reasons, more objective and practical, why those other reforms haven’t happened as quickly but that is a discussion for a future time.

A version of this was originally published on Twitter in August 2020.