charts & data | 2020.12.3

HSR is increasingly affordable in China

Through a series of charts we can see how China’s $900 billion investment in building out its high-speed rail network has impacted traveler behavior and the economy over the last 15 years.

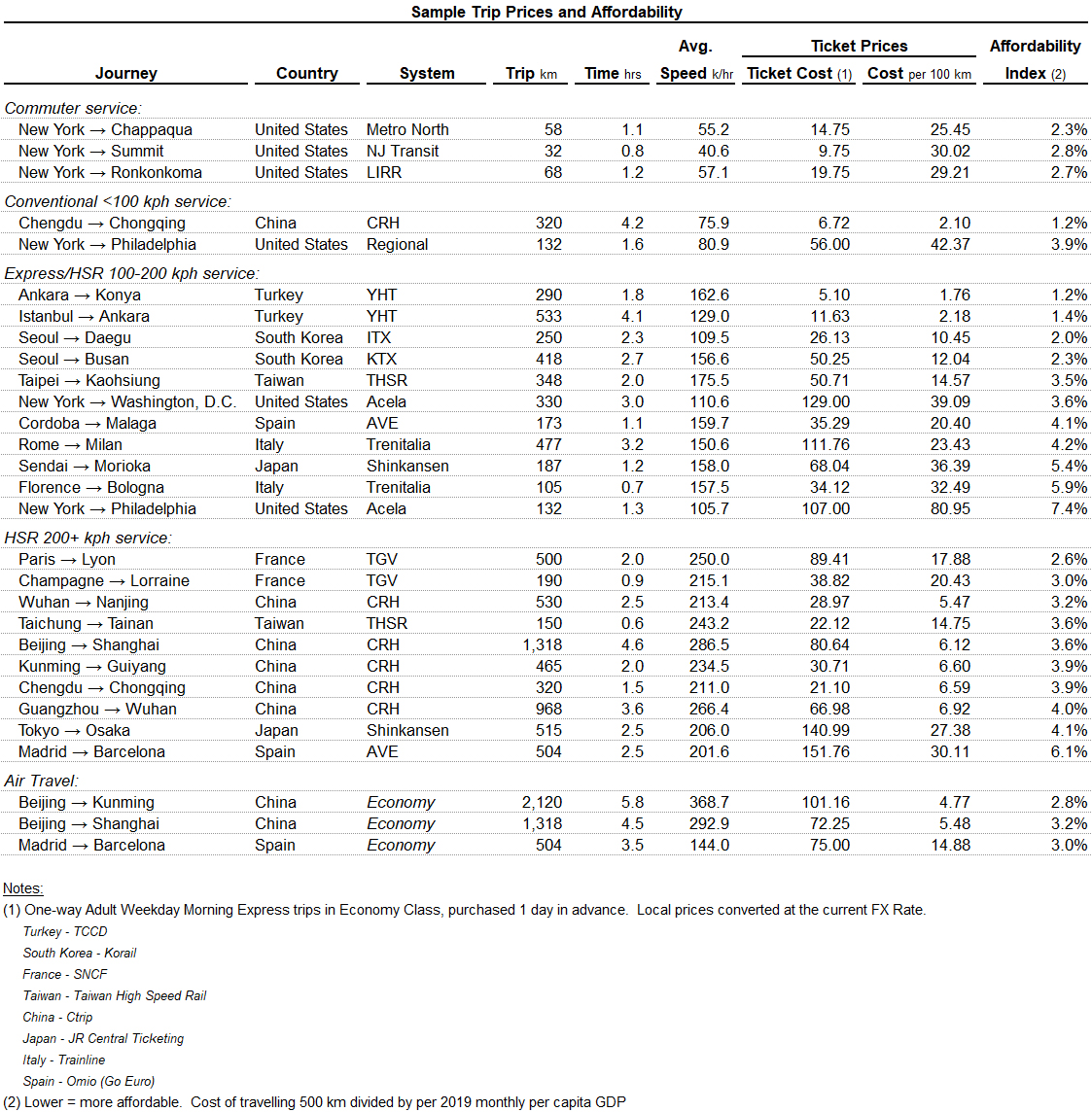

HSR (defined as 200 kph or above) vs. traditional rail service has become increasingly popular over time. 2018 was the first year that saw more miles traveled via HSR than non-HSR.

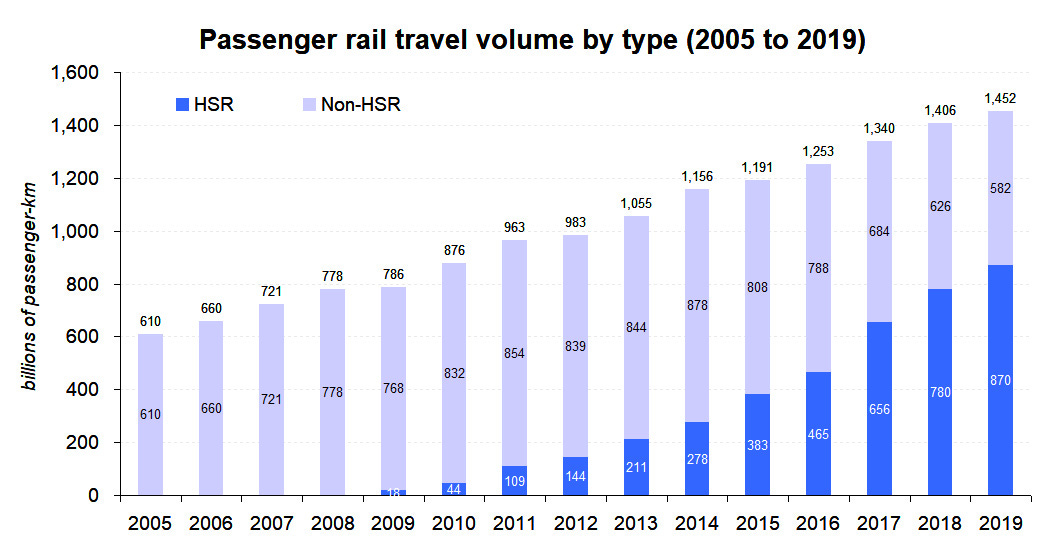

On a per capita basis, Chinese people are traveling a bit over 2x the amount they were in 2005.

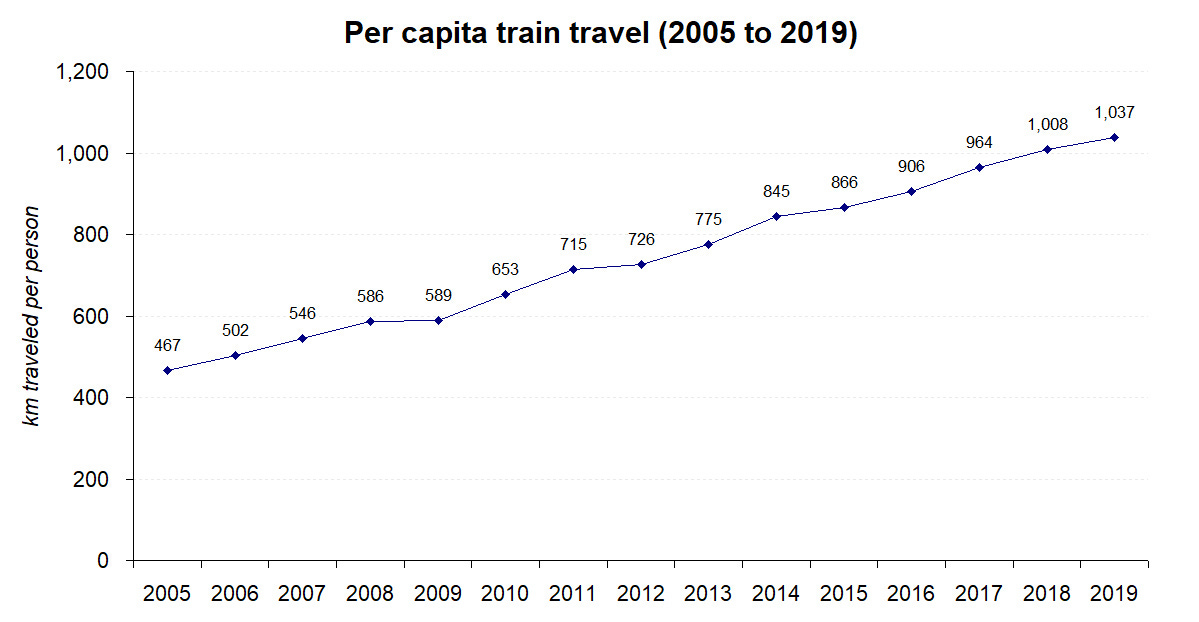

With the shift to HSR, average travel times have fallen. The average time (blended HSR/non-HSR) it takes for a 100-km trip — about the distance from New York City to Trenton — has fallen from 79 minutes to 40 minutes.

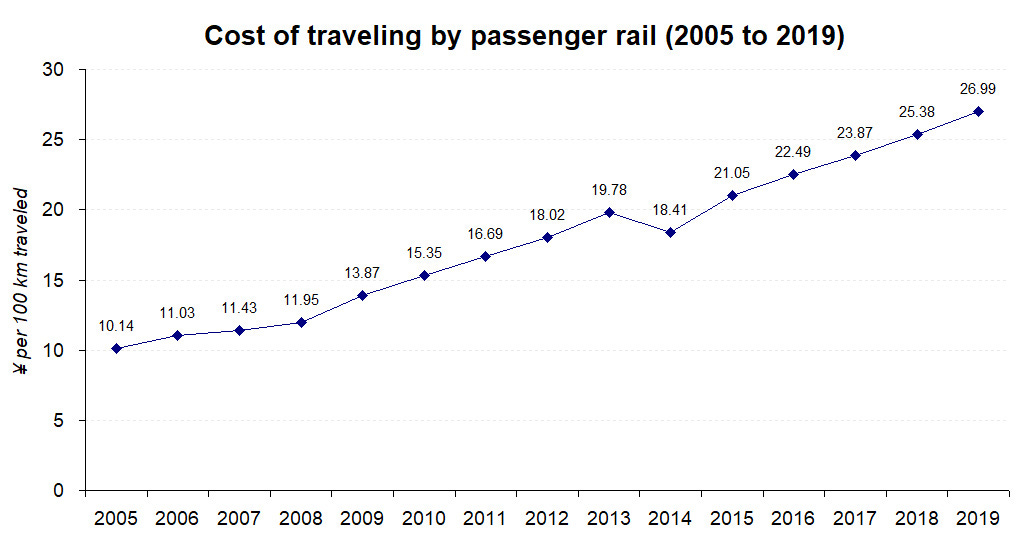

At the same time, the cost of an average train ticket (again, blended HSR/non-HSR) has gone up over time, driven by increasing HSR usage. The average cost of an HSR ticket is about three times more expensive on a distance-adjusted basis.

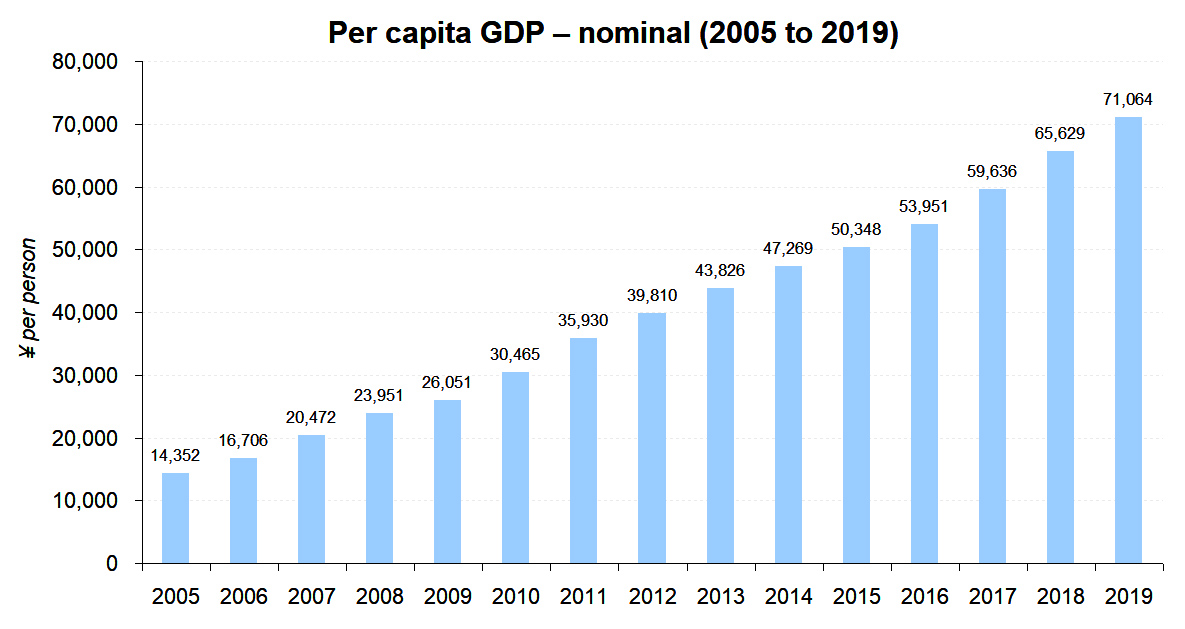

Per capita GDP in nominal terms has increased from ¥14,101 to ¥69,392 over the past fifteen years. Disposable income has increased by the same magnitude.

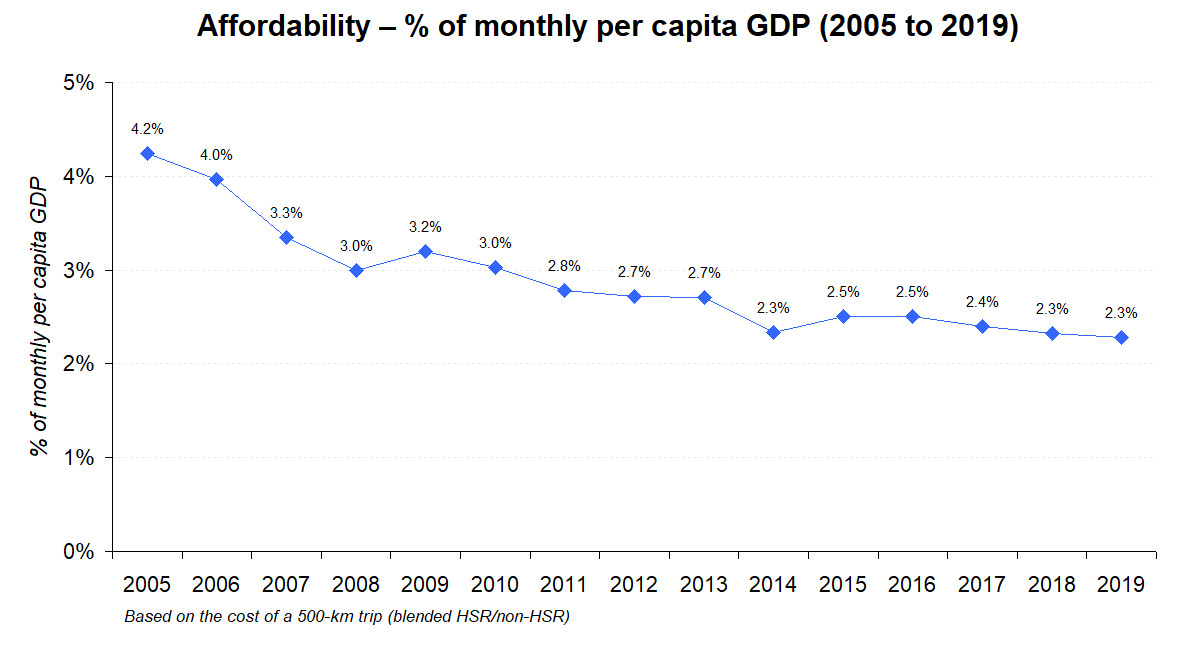

Because of this, train tickets have actually become more affordable over time. In 2005, the average ticket price for a 500-km trip was over 4% of monthly per capita GDP. In 2019, this had fallen to 2.3% even with the shift to higher-cost HSR.

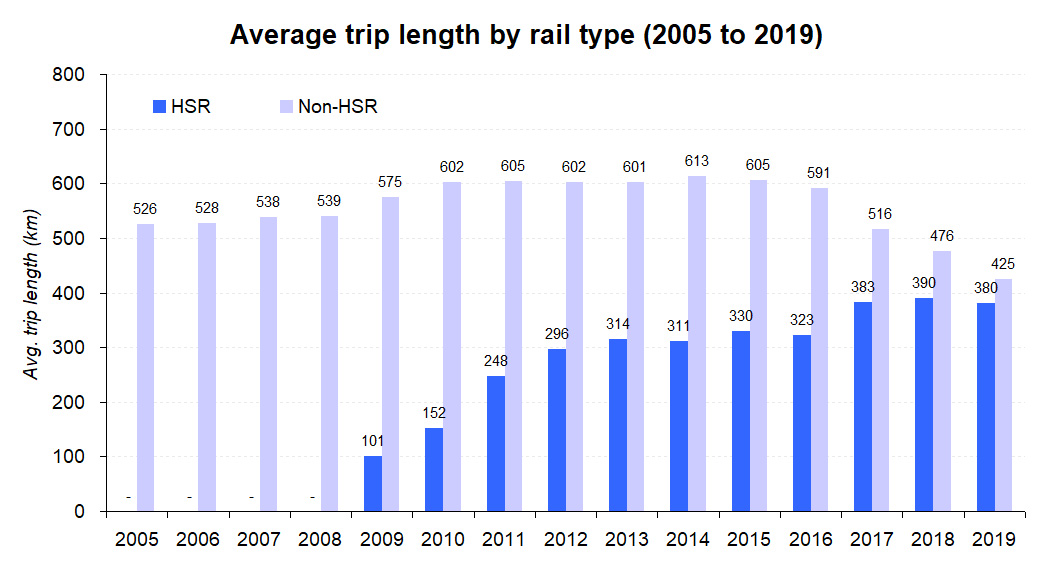

The average trip length for HSR trips has increased over the years. Part of this is because the HSR network itself has expanded, allowing passengers to take longer trips. It does seem to have settled into a sweet spot right around 400 km.

Interestingly, the average trip length for non-HSR trips stayed relatively constant until 2017 when it started dropping. This — and the fact that non-HSR mileage peaked in 2014 — is strong indication that cost-conscious travelers have started to trade up to HSR. In 2018, I wrote about how I started to notice more blue-collar and migrant workers taking HSR in second-class compartments.

In the long run, non-HSR rail will likely be comprised of shorter-length trips where the speed advantage of HSR is muted, or interchange traffic that connects smaller satellite cities and towns that are not covered by the HSR network.

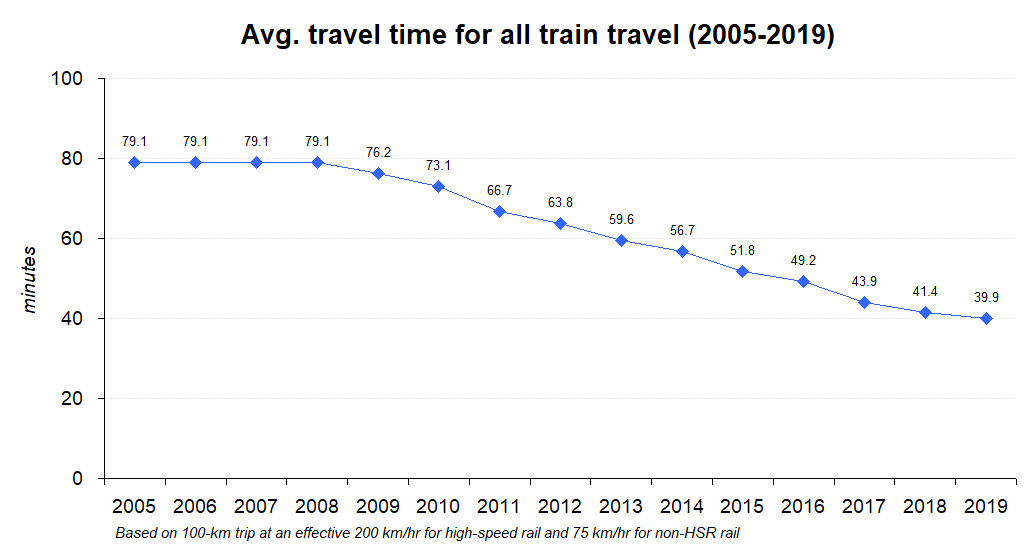

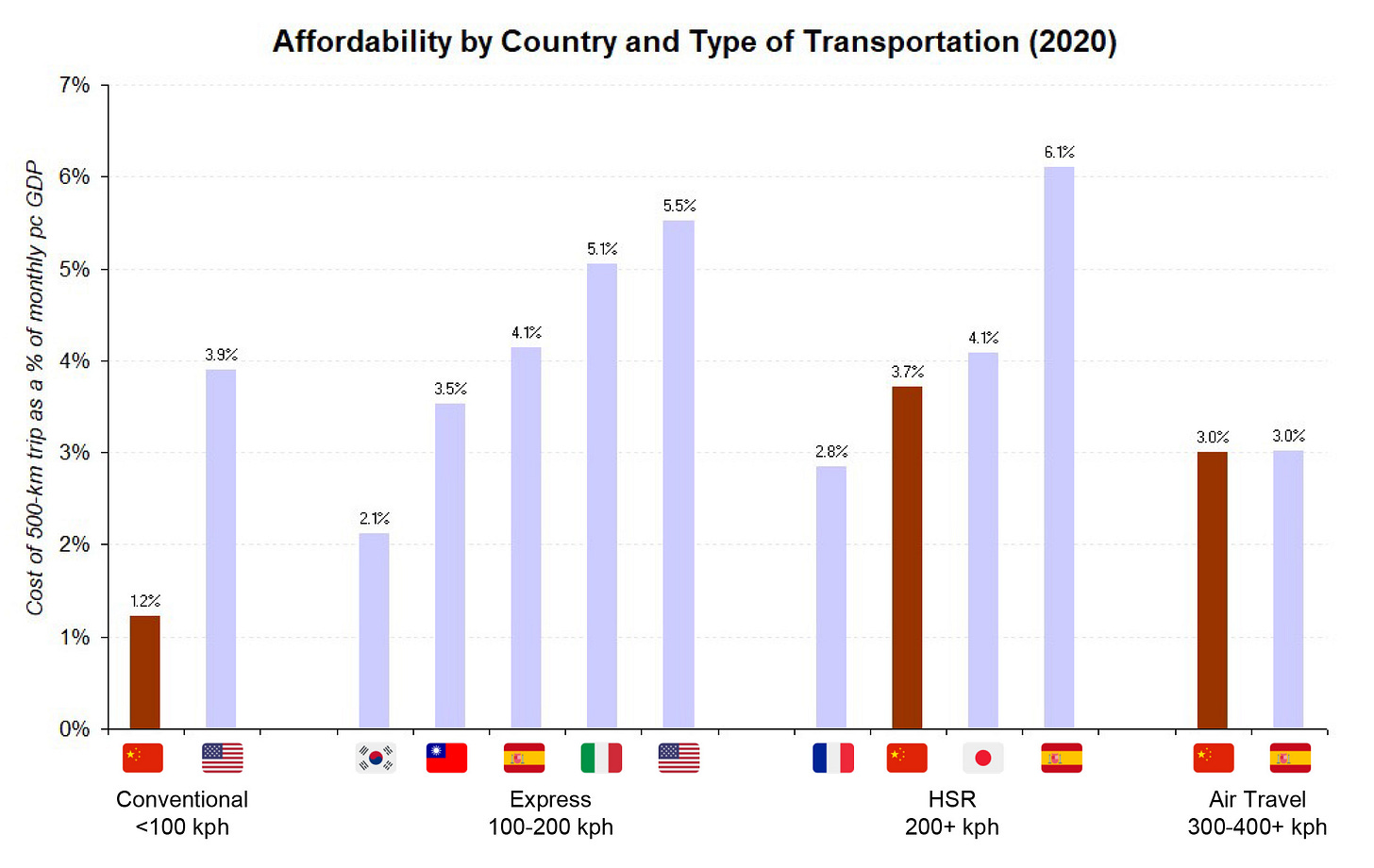

This chart shows the relative affordability of HSR in China compared to traditional rail and air travel in other countries. As you can see, HSR in China is quite competitive, both within the country (vs. air travel) as well as with other countries that have deployed Express or HSR systems.

This chart is based on a sample of ticket prices for economy-class travel from the table below: