What is the cause of our trade imbalance with China?

Examining our bilateral trade deficit

Trade is a two-way street. So we need to look at both sides to see what is really going on here.

In 2017, the United States imported $524 billion of goods and services from China and China imported $188 billion in return. The bilateral trade deficit with China was thus $336 billion.

I’ve summarized data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) in the two tables below:

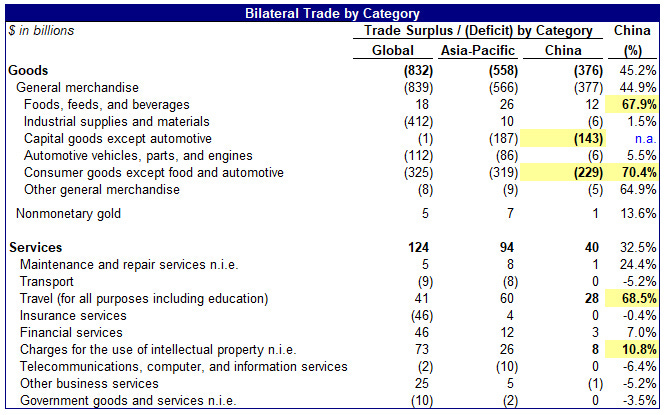

If we look at a further breakdown by category, we see that the two largest categories, accounting for almost the entire trade deficit in goods are “capital goods ex-automotive” and “consumer goods”:

Capital goods — components or finished durable products like motors, industrial equipment, photocopiers, and airplanes.

Consumer goods — usually finished products used by individuals like toys, tennis racquets, and iPhones.

The $376 billion trade deficit in goods is offset by a trade surplus in services of around $40 billion. The two largest categories under services are “travel” and “intellectual property”:

Travel — largely self-explanatory. I would note here that Chinese travelers make up over two-thirds of the trade surplus in travel. If you include the rest of Asia, this figure is over 100%. Essentially, Americans go to Europe and Asians come here for vacation.

Intellectual property — an example of this would be content, software or 4G licensing fees to Qualcomm paid by Chinese OEMs that use their chip design (although these IP fees are often routed through a low-tax jurisdiction such as Ireland).

So based on this we can identify the “culprits”: The reason why there is a trade imbalance is because we are buying too much “stuff” from China and not making enough of it back on the services side. If you are in blame mode, then the other way to say this is that China doesn’t buy enough “stuff” from us and needs to pay more for intellectual property.

The reality is somewhere in the middle. The U.S. needs to consume less and invest more. China needs to consume more and save/invest less.

Actually, I lied. Trade is not just a two-way street. In the modern era, trade is actually more like the crossroads of a hundred different streets in multiple dimensions. Just look at all the components that go into building an iPhone:

So you’ve got components coming in from Japan, Germany, South Korea and the United States … Taiwan is in there fabricating most of the semiconductors … and then China is producing some of lower-tech components like batteries and headphones and providing the labor. If we look at in terms of actual value-add, it looks more like this:

As you can see, China is only about 8% of the iPhone 8 build cost. Once you factor SG&A and profit, the vast majority of which is attributable to the U.S. (as most of the high-paying front office jobs making up SG&A are in Cupertino), the value-add attributable to China is less than 3%.

I haven’t even taken into account the value-add from apps and content, where American companies play a dominant role. Even when a Chinese app developer creates an app, Apple will often take a large cut of the royalty stream through the App Store.

So U.S. workers and Apple shareholders (again, primarily American) take in the vast majority of the value-add whenever an iPhone is sold anywhere in the world. However, because of the funny way in which bilateral trade figures are calculated, China is actually “credited” with the sale of that iPhone (at cost) to the United States. In other words, Apple products actually contribute to the U.S.-China bilateral trade deficit — something that clearly does not make sense.

The iPhone is not just an isolated case either. The vast majority of consumer products, as well as many durable goods that are manufactured in China follow this model:

Other countries export high-value added components and intellectual property to China.

China is also a net importer of commodities like iron and crude oil which are basic components into building the factories where these products are assembled.

China adds a relatively thin layer of manufacturing cost, much of it labor-related. They are now starting to provide some of the more basic components, but continue to lag in the higher value-add stuff like semiconductor components.

China re-exports the product to the end destination and gets credited for the full value of the manufactured good.

The net effect is that while China runs a massive trade surplus with the United States, it runs large trade deficits with other countries/regions like Germany, Switzerland, the Middle East and the rest of the East Asian export bloc. In other words, a significant proportion of the bilateral U.S.-China trade deficit is actually “pass-through” deficit from these other countries. When you hit consumer electronics with tariffs we are actually impacting our own companies like Apple as well as those in close allies like Germany, Japan and South Korea significantly more than China itself.

We know this because China’s overall goods and services trade surplus (around $211 billion in 2017) is significantly lower than its bilateral trade surplus with the United States. I go into quite a bit more detail on this in another answer that focused on China’s balance of payments dynamics.

Indeed, China is far from the worst “offender” when it comes to racking up large surpluses, especially if you look at it on a per capita basis. Here are the economies with the largest current account surpluses and deficits and how they rank on a per capita basis. As you can see below, China runs a per capita surplus of a mere $122, while countries like Germany, Japan and South Korea run surpluses anywhere from 10 to 30x that.

It turns out the causes of our trade imbalance with China are actually more complicated than what you typically hear in the news, especially when there are political agendas at play. So if your goal is to figure out practical solutions on how to address the root issues of the trade deficit, it requires a much more nuanced study of the problem so that we can prescribe targeted medicine — in sharp contrast to our current “slap tariffs on everything” blow-it-all-up approach (mere bluster or otherwise).

The ultimate root cause of the trade imbalance is still that the U.S. consumes too much and China — as well as certain other economies that run large surpluses like Germany, Switzerland and Taiwan — consumes too little. This definitely needs to change — and I think this has been changing, at least from China’s side. China started to seriously shift from an export-oriented industrialization model to a more consumption/services-oriented growth model starting around 5–6 years ago. Of course, there is the separate question of whether in shifting to more consumption, that more of this consumption is actually being imported or ultimately being provided by domestic producers.

On the other hand, in my view we have not done as much to shift our consumption habits. Our aggregate trade deficit has gotten a nice tailwind from the reduction in our crude oil import bill, both from the rise of domestic production from “tight oil” and the decline in global commodity prices. A relatively benign monetary environment has mitigated the cost of the extra federal debt that we have taken on from years of accumulated trade deficits. This has to a certain extent masked the long-term effects of the American economy’s over-reliance on consumption (at the expense of investment), a trend that really started over thirty years ago during the Reagan administration.

We need to invest more and consume less. But we need to be smart about how we invest as well. For example, I vehemently disagree with the notion that we should be trying to increase our investment effort by trying to “take back” industries and supply chains that departed many years ago.

Maintaining existing industries that still have critical mass in the U.S. is another question, one that I generally support (we definitely should not be reducing tariffs any further). Part of the reason why we let certain types of jobs go (e.g. labor-intensive manufacturing) long ago is because Americans weren’t willing to work for such low wages.

As I wrote earlier, we need to follow the advice of hockey legend Wayne Gretzky:

“I skate to where the puck is going to be, not where it has been.”

In other words, we need to look forward and support the industries of the future, not backward at the industries and jobs of the past. The Chinese most certainly are.

We need implement strategies where we control more of the variables, instead of strategies that rely on others to be successful (e.g. trying to get an entire global electronics supply chain to shift back to the U.S. — just not going to happen!).

We should aspire to set an economic foundation that allows our children to do more interesting and stimulating types of work, not forcing them to go back to doing the same kind of work that our parents and grandparents did generations ago.

We also need to better understand the negative effects of future disruption — job losses, detrimental effects on certain specific communities and regions etc. — and improve our strategies on how to handle them. Any modern innovation policy needs to include solutions to mitigate these inevitable negative effects while still maintaining enough incentive for entrepreneurs to continue to innovate. It’s a balancing act, but one that we need to get right to continue as the leading economic power in the world in the decades to come.

This was originally published on Quora in September 2018.