Bike-sharing in China: Success or colossal waste?

Now that all the dust has settled

SCMP: What happens to discarded bikes from China’s sharing boom?

The massive clean-up closes the book on one of the country’s more quirky technological phenomena: the bike-sharing bubble that came from zero to a peak and a rapid deflation, all within four years. The boom-to-bust cycle burned up tens of billions of dollars of investments, turned several tech entrepreneurs into billionaires, but also passed the associated environmental and clean-up cost to society at large.

The prevailing narrative on dockless bike-sharing is that it was a “disaster” due to waste and congestion. But the numbers show that if anything it has been an unmitigated success.

The narrative fails to account for the fact that these bike-sharing services are used a lot: In China, upwards of 12 billion times a year. This massive ridership has major implications.

First, there is the direct economic value it generates. Dockless bike-sharing is now embedded into the urban fabric of Chinese cities and fills the gap as a transportation alternative for shorter routes. Every day 30+ million riders make a calculated economic decision to choose this form of transport over others. At a ¥ ($0.15) per ride, this is $1.7 billion per year of economic value.

Second, the intangible benefits: 12 billion trips per year x 1.5 miles per trip x 0.5 lbs of CO2 saved = 4.7 million tons of carbon saved. Valued at $50 per ton, this is worth $233 million a year in environmental benefits.

Third, there are also health benefits. Citibike estimates 40 calories burned per mile. 18 billion miles a year = 720 billion calories burned. Plus more breathable air: Not sure how to value this but this is also not insignificant.

Let’s put the costs in perspective. 25 million discarded bicycles sounds like a colossal waste in a vacuum. That’s certainly the implication of all those flyover montages of “bicycle graveyards”. But maybe it’s not that bad in the grand scheme of things.

First, ~80% of the bicycle can be recycled. The article states that the gross recyclable value of each bike is ~¥20-30 per bike.

Second, the article makes the key point that the burden of disposing these bicycles falls onto local governments — so meaningful a point that it headlined the article. But how significant was this really? The article points out that the city of Dongguan paid ¥8 (~$1.18) per bike to clear them off the streets. Multipled across 30 million bikes across the entire country: ~$35 million for the entire stash. Not exactly a huge burden.

But a key point here is a fundamental misinterpretation of what these discarded bikes actually represent. Was it all just a waste?

Let’s go back to the ridership numbers: These bikes are used 12 billion times a year. That’s a tremendous amount of usage — which leads to a tremendous amount of depreciation, both financial and actual. Anybody who has a bike knows how often they break down, especially if they are constantly exposed to the elements.

A good number of the bicycles in those “bicycle graveyards” were there because they had been used rather intensively. At the same time, many bicycles were discarded because of the rapid innovation in bicycle design that quickly obsoleted older designs:

As detailed excellently in this podcast, the shared bike companies had to essentially re-design the bicycle from the ground up for this new use case. One implication of this is that the first couple generations of shared bicycles had design problems which led to a high percentage of them having to be discarded. In other words the depreciation rate was very high for the first couple iterations of bicycles as the entrepreneurs figured things out and learned from their mistakes.

So instead of a story about colossal waste, perhaps the real story of these “bicycle graveyards” is of an innovative, environmentally friendly form of alternative transportation that was enabled by the convergence of multiple technology trends.

This is not to downplay the fact that there was most certainly an element of over-building in the initial investment frenzy. But this also needs to be quantified and put in perspective.

One way to do this is to look at overall capital efficiency. I estimate that around $8 billion of investment capital went into dockless bike-sharing, $5 billion to the top 5 players. Within 5 years of inception, the industry had consolidated from 70+ to three major players (HelloBike, Mobike/Meituan, and a subsidiary of ride-hailing service Didi). This cycle of “invention – land grab frenzy – consolidation – equilibrium” is very common in China.

The remaining players have also largely solved the congestion issue by working directly with local governments and consumers on reasonable solutions. For example: coming up with innovative solutions like bluetooth road stubs to create designated parking zones.

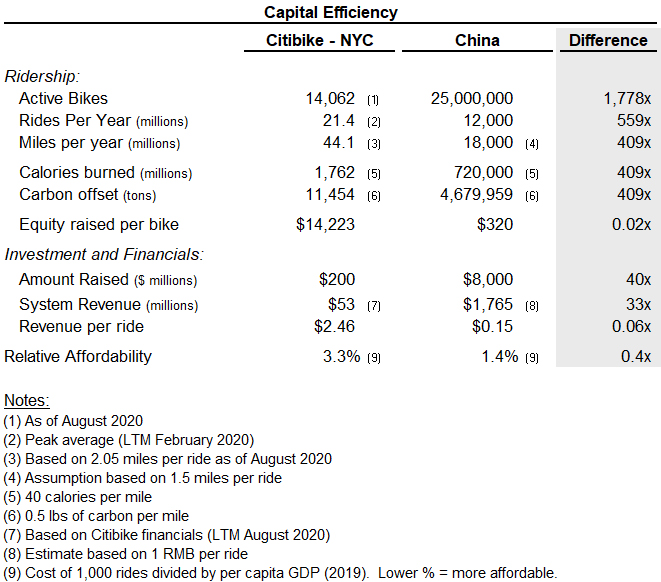

Without disclosed financials, it’s hard to figure out how financially profitable (or unprofitable) these operations are. But we can take a look at Citibike in NY to get some perspective on the capital efficiency of China’s bike-sharing industry.

For ~$200 million of initial investment, Citibike has deployed ~14,000 docked bikes and provided 21.5 million rides per year at its peak (pre-pandemic). Citibike generates average revenue of $2.46 per ride, including sponsorships.

For $8 billion (40x) investment, dockless bike-sharing generates 12 billion rides per year (560x) in China. At a cost/ride that is more than 10x less ($0.15), this results in 33x the revenue. This is before factoring in the positive environmental/health benefits which would of course be proportional to the number of rides.

The big cost difference is in the cost to deploy each bike. In China, it cost $320 of up-front investment per bike while in New York City it cost over $14,000. This is primarily because the docking stations are so expensive and make up the majority of Citibike’s system cost.

The numbers are pretty clear. Each dollar of investment in bike-sharing in China was at least one order of magnitude more impactful or efficient.

$8 billion of up-front investment and a few years of congestion as cities figured out how to incorporate dockless shared bikes seems like a reasonable price to pay for $1.7 billion (and growing) per annum of recurring economic value and all of the ancillary social and environmental benefits.

A version of this was originally published as a Twitter thread in October 2020.