22% of China’s GDP goes to Debt Service?

Gross vs. net

Some interesting recent headlines from the fringes:

ZeroHedge: A Record 18% Of China's GDP Goes To Debt Service

While China exited ‘17 with an est. 266% of total credit to GDP, some economists put that ratio at >300% today. On trailing 12-mo. nominal GDP of ¥86.5tn, as of 2Q, this equates to >¥259.5tn in credit, which, assuming an avg. borrowing cost of 6%, means China’s annual debt service is ~¥14.3tn, or 18.0% of GDP – sensitizing interest & credit-to-GDP, to a respective range of 4-7% & 285-320%, puts China’s debt service at 14-22% of GDP.

This has been picked up in Twitter-land:

As I explain in my response, this is just another example where a simple narrative — in this case the “China Credit Bubble” one — is applied to a complex, nuanced and generally not-well-understood topic.

In this case, the topic is credit intermediation, how it is performed differently in China vs. the United States, and how easy it is to be misled by simple logic that seems sound from the outside.

As I have discussed before, China’s total debt figure reflects both a rise in the underlying amount of credit provided as well as the increasing complexity of the financial system. So when China’s total debt increased from around 200% of GDP in 2012 to close to 300% today, some of this was driven by growth in “primary” lending and some of it was driven by the increased complexity in the system (which leads to a certain amount of “double-counting”).

The “22% of GDP” figure originates by essentially taking the 300% debt-to-GDP figure and slapping on an “estimated 7%” cost of borrowing. Seriously, it’s that simple.

The problem is that depending on the degree of double-counting due to credit intermediation, a significant portion of the interest expense related to all 300% debt is offset by interest income generated in the middle stages of credit intermediation.

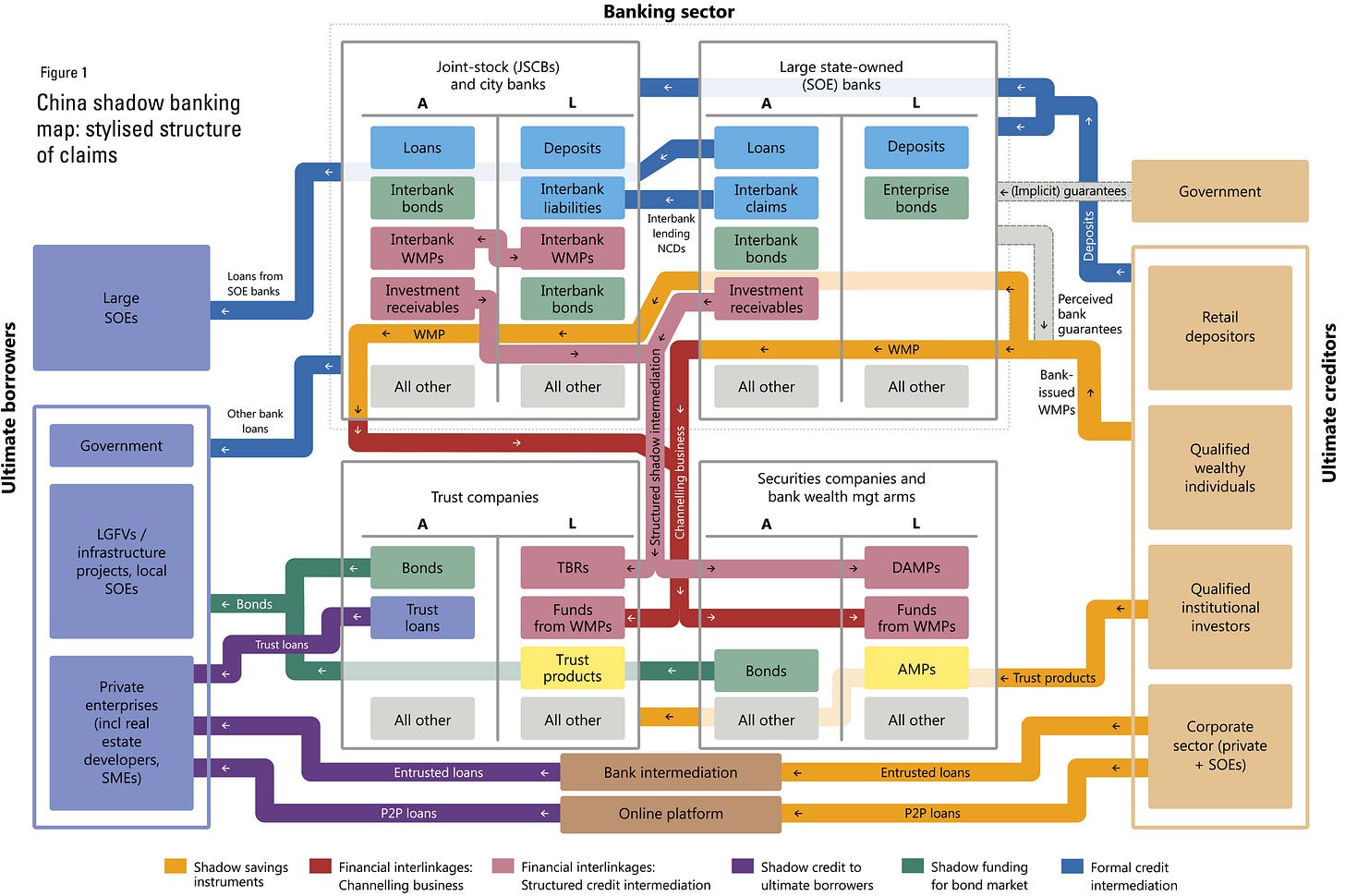

For example, as described in this chart from an excellent report from BIS (page 4), here is a typical “shadow banking” flow of how funds get from the ultimate creditor (e.g. an individual) to the ultimate borrower (e.g. a private company):

Say Mr. Li just sold his nice flat in Nanjing and deposits RMB10 million into the local branch office of Bank of China. Deposits earn interest at say a 3% rate.

His account manager recommends that he move the funds into higher-yielding Wealth Management Products (“WMPs”). These WMPs earn interest at a 4% rate. He agrees.

Bank of China then “channels” those funds earmarked for WMPs to a Trust Company. This Trust Company is responsible for sourcing new loans, and it specializes in small private enterprises (which have traditionally had a tough time sourcing debt capital). It has found a group of a dozen private companies that need funds and aggregated them into a pool.

The Trust Company re-lends the funds that were channeled from Bank of China in the form of “Trust Loans” to these various private companies. It charges interest at an 8% rate, to reflect the risk that it doesn’t get repaid and to cover costs of originating and servicing the loans.

In this example, from the original RMB10 million in funds, a total of RMB20 million in new gross credit is created:

There is the RMB10 million in WMPs and the RMB10 million in trust loans to the private company.

This gives rise to a total of RMB1.2 million per year in incremental gross interest expense:

4% on the WMP, or RMB0.4 million per year

8% on the trust loan, or RMB0.8 million per year

One of the main ways GDP is calculated is through something called an expenditures approach. This is the approach that China adopted in 1993.

GDP is not calculated by just adding up every individual’s gross spending and every company’s gross revenue.

That is because one company’s revenue can be another company’s expense. One person’s spending is the revenue for somebody else. In really complicated supply chains you could have gross revenue that is many multiples of the actual economic activity of the system. This is the same concept of double-counting we are talking about above.

Instead, GDP is calculated by looking at economic value-add, or the incremental value that you have added above and beyond the inputs that you have taken in. A company’s GDP contribution is going to be much closer to its profits than its revenue.

So for Bank of China in the above example, its GDP contribution is not the total interest income it is earning by lending out RMB10 million, it is something called a “net interest margin” that subtracts its cost of funding. This should be a fundamental concept to anyone who has analyzed the financial statements of banks and financial institutions.

In other words, GDP is calculated by looking at things on a net and not a gross basis.

Knowing this, it should start to become very clear why taking a gross figure (gross interest) and dividing it by a net figure (GDP) to arrive at an answer (22%) starts to become problematic.

This was originally published on Quora in January 2019.